Bladder, Urethra and Ureters

Uroabdomen

Risk factors

Uroabdomen is typically seen with parturition or urolithiasis. For horses, the most common population is 1-2 day old colts that have their bladder squeezed too much during parturition. Occasionally the dam suffers a ruptured bladder due to compression of the bladder between the foal and the pelvis. For ruminants, the most common cause is urolithiasis – goats, steers, and pigs in particular.

Diagnostics

Foals are normal at birth, with no signs of illness for 24-48 hours. They then become lethargic with a decreased interest in suckling. Some foals will become colicky (show signs of abdominal pain).

Many can urinate normally. Occasionally a foal will be anuric or void only small volumes of urine.

Abdominal distension develops over time. Abdominal distension can occur due to many reasons. A common mnemonic is 7(or more) F words:

| Flatulence | Fetus | Fat |

| Fluid (urine, ascites, peritonitis) | Freaked out cells (neoplasia) | Free gas (ruptured bowel) |

| Frank hemorrhage | Feces (impaction) |

In a neonate, impactions, gas and urine would be the most common. A fluid wave may be detectable.

Foals will be tachycardic. Some foals will develop pleural effusion and tachypnea.

Ultrasound is a key diagnostic test. With a ruptured bladder, a large amount of free abdominal fluid is visible. While a 5 MHz linear transducer is okay; 7.5-10 MHz best. Occasionally you may see collapsed bladder ± tear with fluid exiting it. Another trick is to inject “agitated” saline solution (regular saline that has been shaken up) into bladder. This makes it easier to identify the site of the tear as you watch air bubbles exiting bladder The ultrasound can also help determine a safe site for abdominocentesis and drain placement. The thorax should also be scanned; pleural fluid isn’t common but does occur. Obviously thoracic fluid would add to the anesthetic risk unless removed (via thoracic drains).

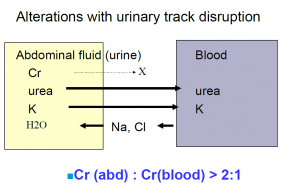

Peritoneal fluid analysis can also be used to confirm uroabdomen. Due to the size of the molecule, we use creatinine to determine if the fluid in the belly is urine or not. Creatinine doesn’t equilibrate so we can compare the abdominal fluid creatinine to the serum creatinine. If the concentration in the abdominal fluid is at least 2x the concentration in the blood, it is urine. Heating the fluid is often a quick and dirty way to tell, too.

Serum chemistry will typically show increased creatinine, BUN and potassium along with decreased pH (acidosis), sodium and chloride. PCV/TPP and white blood cells are elevated. In foals, IgG should be evaluated to ensure colostral absorption.

ECG monitoring is recommended due to the hyperkalemia (watch for tall peaked T waves due to rapid repolarization).

Treatment

Stabilization prior to surgery is required. Electrolyte and fluid shifts should be corrected. Uncontrolled hyperkalemia can lead to death due to arrhythmias. Sodium chloride and sodium bicarbonate are given iv (avoid LRS due to the potassium in the fluid). Dextrose and insulin are administered to drive potassium into the cells where it is safely sequestered (0.5 g dextrose/kg bwt; 0.1 unit insulin/kg bwt iv). Urine should be drained from the abdomen/thorax to enable better ventilation and to remove the toxins. The foal should have a normal temperature, glucose and hydration prior to surgery.

Bladder repair in foals, goats and pigs is performed under general anesthesia. Once the potassium is <5.5 mEq/L, anesthesia can be performed. Bladder repair in mares is possible in the standing patient, assuming the patient is amenable to standing surgery.

Differentials

Uroabdomen can also occur with ureteral tears, urachal leakage/ urachal necrosis in10-14d old foals), meconium impaction in neonatal foals and neonatal maladjustment/ septicemia.

Ureteral tear

Fillies with uroabdomen should be checked for ruptured ureters since ruptured bladders are less common. With a ruptured ureter, urine accumulates retroperitoneally, as well as intraperitoneally. While ultrasound can help in certain cases, antegrade pyelography (inject contrast into the renal pelvis and watch its exit path fluoroscopically) can be very useful in identifying any leaks in smaller patients. Scintigraphy can be used in larger animals.

Treatment involves ureteral catheterization (from the bladder) with retrograde dye infusion to identify the defect. The catheter is then advanced to the renal pelvis and the defect repaired with absorbable suture. The catheter may be left in place as a stent with distal end exited out either the urethra or via a perineal urethrotomy. In the older gelding, conservative treatment with antibiotics, NSAIDs and fluids was adequate without stenting as the ureter remained patent.

Resources

Uroperitoneum in foals, Merck online- nice overview of how these babies look