LA Orthopedic Emergencies

Arterial damage

Arterial bleeding can be rapidly life threatening. Most arterial lacerations are caused by external trauma; fractures can also lacerate arteries and cause severe bleeding without an external wound.

As with most arterial bleeding, compression, ligation or vascular repair is typically needed. In large animal species, collateral circulation is generally sufficient to provide blood flow to an area; rarely is vascular anastomosis required or performed.

Blunt force or stretching of an artery can lead to clotting and stop blood flow without laceration or hemorrhage. Thrombosis occurs due to damage of the wall and release of tissue factors.

Bleeding secondary to artery laceration

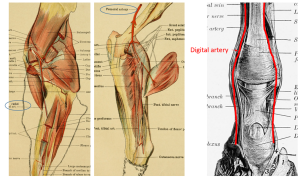

Pastern lacerations are one of the more common causes of arterial injury; this is due to the limited soft tissue covering of vessels in that region. Accidental artery trauma can occur in surgery, as well.

Bleeding can be controlled through

- tight bandages

- temporary tourniquets

- ligation of the artery

- clamping of the artery

- patient death (obviously not ideal)

Horses may not tolerate tourniquets and tight bandages on hindlimbs as these are painful. Most will require sedation if a tourniquet is needed. Cattle and small ruminants are more amenable to treatment but also deserve analgesics. Animals can be sedated and/or anesthetized if needed; fluid support is often indicated due to blood loss. Anesthesia often seems dangerous in animals with blood loss; however, short duration anesthesia that results in hemorrhage control is generally preferable to ongoing blood loss.

Bleeding secondary to bone fracture

While pastern fractures can lacerate the digital artery, femoral fractures and radial fractures are the most likely causes of arterial lacerations secondary to bone fractures. For the femur and radial fractures, damaged arteries are deep and not accessible without significant surgical trauma. Substantial bleeding can also occur from the bone itself. Compression can be almost impossible due to the large muscle mass. Keeping the patient quiet and calm (lowered blood pressure) is essential.

While pastern fractures can lacerate the digital artery, femoral fractures and radial fractures are the most likely causes of arterial lacerations secondary to bone fractures. For the femur and radial fractures, damaged arteries are deep and not accessible without significant surgical trauma. Substantial bleeding can also occur from the bone itself. Compression can be almost impossible due to the large muscle mass. Keeping the patient quiet and calm (lowered blood pressure) is essential.

Various therapies to activate clotting and/or slow bleeding are usually attempted:

- iv formalin (11-50 ml 10% neutral buffered formalin/ liter LRS)

- EDTA

- ice packing

- yunnan baiyao

In many cases, a blood transfusion will be required. Once the bleeding has stopped and the patient stabilized, referral to a hospital with transfusion capability is indicated.

Arterial spasm/ arterial blockage

When arteries are stretched too far or are traumatized, they tend to spasm shut. If this spasm lasts long enough for clotting to occur or causes endothelial damage, eventual loss of distal blood flow is very possible. In these situations, all blood supply to a region tends to be impacted. Without blood supply, the extremity becomes necrotic. Such injuries end in amputation or loss of life.

The most common causes of this type of injury are racetrack breakdown injuries, limb entrapments, and cannon bone fractures due to dystocia management in neonatal calves. In the latter two cases, the vessels are compressed by outside forces (whatever is entrapping the limb and the calving chains).

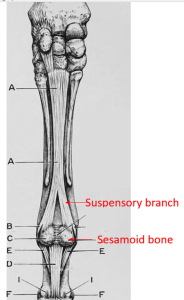

Breakdown injuries (suspensory breakdown or fetlock breakdown) occur when the fetlock is hyperextended. This can be due to rupture of both suspensory branches, fracture of both sesamoid bones or fracture of a pastern bone. With breakdown injuries, the fetlock drops so low that the vessels are stretched almost to the breaking point.

In all of these situations, the blood flow damage is not immediately obvious. However, within 6-12 hours, the limb is noticeably cooler. The prognosis is very poor. Healing does not occur without blood supply. Larger animals do not tolerate limb amputation and should be euthanized unless some sort of prosthesis is available (and this is rare). Small ruminants and alpacas can tolerate limb amputation and this is an option.

Occasionally, infections and endotoxemia lead to systemic clotting. Distal limbs are affected first. This can result in hoof sloughing as one of the early signs. This is due to the limited blood supply to the hoof as well as the small diameter vasculature that clots more readily.

Key Takeaways

Apply pressure or ligatures to stop bleeding, even if it means anesthesia

If the hemorrhage is due to a fracture of the radius or femur, you need lots of luck to control it.

If the fetlock hyperextends, the vessels may thrombose (breakdown injury).

References

Intravenous formalin for treatment of haemorrhage in horses. Equine veterinary education, 2021-03-08

Fetlock breakdown injuries. WestVets.com