Equine Lameness

The parts of a lameness examination

No hoof, no horse. No limb, no horse. Lame horse, money lost. (Horses are expensive lawn ornaments.) Veterinarians spend a lot of time evaluating horses for lameness. While equine lameness was responsible for 11% of emergency visits in a UK study, owners may not always identify a lameness. They may report that the horse is just not performing as well or seems unhappy about the work. Horses may also be presented for a prepurchase examination in order to verify soundness (no lameness) prior to being purchased by a new owner.

The goal of a lameness examination is generally to localize the lameness into a region that can be targeted with advanced diagnostics (eg will fit on a radiograph screen). We also want to have a systematic approach to the lameness examination in order to be able to reassess the horse effectively at a later date (eg is the lameness better, worse or about the same after stall rest).

Key components of a thorough lameness examination are the history, visual examination, passive examination and active examination. Once the lameness has been localized to a limb or part of a limb, more specific diagnostics are performed, including imaging and blocks. If the lameness cannot be localized, scintigraphy may be useful.

The history

When evaluating lameness, context is crucial. Beyond the presenting complaint and a general health history, we need to know a lot about the situation.

What is the horse is supposed to be doing? Backyard pleasure? Grand Prix Jumper? When is it supposed to be doing this? Tomorrow? Next year? Owners may have high hopes and unrealistic expectations but it is always useful to know what they are.

How hard and how frequently the horse is worked? Horses may be lunged (worked in a circle) in soft footing as a warm up -this is tough work! How long do they do this? How many days of the week does the horse work? How long is each work out? What is the footing? How often is the horse competed?

Horse owners also tend to medicate their animals. Is the horse currently on medication? Has it received any medication? What type and for how long? Did it make a difference? Is the horse on any supplements? Note: they may not consider supplements as medications so you may have to ask specifically about supplements!

Horse housing varies: they may be outside 24 hours a day or inside all of the time. Standing is a stall is different from free choice exercise. What is the horse’s environment? Note: If the horse has been prescribed stall rest, ask open ended questions. Horse owners will often give up on stall rest and be reluctant to admit it directly.

Horses are athletes and some get regular therapies. It is very useful to know if the horse has had surgery or joint injections before. If they have been treated before, when was it and how did the horse respond?

Hooves grow over time. If the horse is due for a hoof trim (most get trimmed every 6-8 weeks) or needs a shoe reset, that can change your interpretation of radiographs and can affect treatment plans.

Because a horse can’t move on three limbs, weight shifting does need to happen when a horse is lame. Owners might notice secondary shoulder pain (foot issue) or back pain (hock issue). They may call you to evaluate the shoulder or back instead of the feet or hocks. In actuality, the horse is shifting how it moves because of the foot and/or hock pain. It may have sore shoulders and a sore back but these are secondary to the original pain.

The visual examination

Prior to nearing the horse or touching the horse, evaluate the overall appearance, conformation, stance and symmetry (along with attitude). Is the horse shifting weight equally between limbs? Shifting weight excessively? Not putting weight on a limb? Pointing a limb? Are any limbs or parts of limbs swollen or atrophied?

The passive examination

The passive examination is performed with the horse standing still, often during history collection. The horse is palpated from poll to toes and assessed for range of motion of joints (how well do they bend), lumps and bumps, fluid in tendon sheaths and joints, and warm or painful areas. Knowing the palpable anatomy is crucial. Hoof structure, shoe wear and tear and hoof balance is also evaluated. Abnormalities are recorded for consideration after the active examination. Not all will turn out to be significant.

Back palpation and sternal lift (this horse is sore)

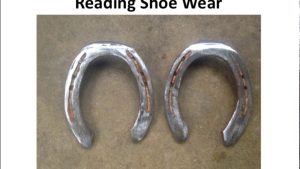

Shoe and foot examination

If a shoe is present, it should be checked to see if it is loose, if it is an appropriate size and if it has any uneven wear patterns that would indicate the horse is not moving forward smoothly and straightly but is “winging” or “paddling” its limbs. Some shoe types will also indicate that the horse is working in a specific performance area or is being treated for a foot condition. Feet should be assessed to determine if the coronary band is parallel to the ground or if the hoof wall is uneven. The foot should also be checked for founder rings, cracks and other issues. More information about hoof conformation is in a later chapter.

Hoof tester examination

Generally, hoof testers are applied as part of the passive examination. Large tongs are used to pinch the hoof. A consistent withdrawal of the limb each time the hoof tester is applied is indicative of pain. [A single withdrawal means the horse doesn’t want this exam done but doesn’t necessarily mean pain.] Pain over the heel region is often associated with navicular syndrome issues. Pain in other areas could be a hoof abscess, sole bruise or laminitis. Pain all over (no distinct area) is often a hoof abscess or a fracture.

using hoof testers – great images

Churchill hock test

This tests checks for pain in the lower hock joints (bone spavin). It is performed by trying to pull the medial splint bone around to the lateral side of the leg. If painful, horse will react by abducting the leg (not positive if he pulls back or forward; has to pull away from the source of pain on the medial aspect of the leg).

The active examination

The horse is evaluated at a walk and a trot as part of most examinations. Occasionally the horse is worked at a canter and/or ridden. If the horse is lame at a walk, we do not usually trot it. During the moving examination, we look for uneven weight bearing and rapid recovery (move to the other limb). Head nods and hip excursions (described below) do not always work well at the walk. The trot is a two beat gait which allows overall shifts in weight to be evaluated since one hind foot and one fore foot are on the ground at one time. At a canter, the horse can protect a lame limb by using one “lead” – one leg starts the stride, the other 3 follow. Horses with significant lameness will prefer to canter rather than trot.

Note: If you are worried about a fracture (from the history, level of pain), DO NOT TROT the horse. Incomplete fractures can become complete fractures.

Most vets use the AAEP 5 point scale. This allows someone else to evaluate the horse and determine if the lameness has changed. Grade 5/5 is non-weightbearing, while grade 1/5 is a lameness seen only under certain conditions.

0: Lameness not perceptible under any circumstances.

1: Lameness is difficult to observe and is not consistently apparent, regardless of circumstances (e.g. under saddle, circling, inclines, hard surface, etc.).

2: Lameness is difficult to observe at a walk or when trotting in a straight line but consistently apparent under certain circumstances (e.g. weight-carrying, circling, inclines, hard surface, etc.).

3: Lameness is consistently observable at a trot under all circumstances.

4: Lameness is obvious at a walk.

5: Lameness produces minimal weight bearing in motion and/or at rest or a complete inability to move.

Horses are evaluated from the rear, the front and the side. We are looking for symmetry, stride length, foot flight and foot placement.

Footing

Horses may be worked on both hard and soft footing. Hard footing emphasizes weight bearing issues (a bone bruise will be worse on hard footing), while soft footing emphasizes soft tissue issues (a tendon injury will be worse on soft footing). This is akin to you running on pavement (concussive) or on sand (tendon stress).

Lunging

Horses are also worked in a circle (lunged). Lunging exacerbates weight bearing issues on the inside limb and soft tissue issues on the outside limb. A horse that is bilaterally lame won’t show as much lameness on a straight line as the horse can’t pick a limb to protect. We may not see a nod or change in hip excursion. Often we just see a short, choppy gait. When the horse is lunged, however, now one leg is working much harder than the other and we can see lameness. We lunge the horse in both directions to ensure we have found all the affected limbs.

This horse is very stiff (and sore) – note how it holds it’s body

Stress tests

Stress tests are used to try and confirm lame limbs or to localize the lameness. Taking full limb radiographs on a horse would cost over $1000 so we need to better define what we want to image. We do this noninvasively through flexion tests (bend the limb and stress the joints) and wedge tests (a bar is put under different parts of the horse’s foot to stress different areas).

In most lameness exams, the distal limb will be flexed on both fore and hindlimbs. ,The lower limb is bent to stress the coffin joint, pastern and fetlock joints. It is impossible to flex these joints individually. The person flexing the limb avoids putting pressure on tendons or ligaments as pain in these regions could complicate the interpretation. After 30 seconds of holding the joints in flexion, the horse is trotted off and the lameness reassessed. Often the first 1-2 steps will show pain; these are generally ignored and the examiner focuses on the later steps. Persistent lameness is called positive and typically represents joint pain.

In the forelimb, the carpus can be flexed by itself. This flexion is held for 60 seconds. In the hindlimb, the reciprocal apparatus makes it impossible to flex any normal joint all by itself. The distal limb, stifle and hip will flex when the hock is flexed. The upper limb flexion is often called a spavin test. This test is not terribly specific so we are trying to determine if it is markedly worse than the distal limb flexion. A positive spavin that is worse than a distal limb flexion would suggest hip, stifle or hock pain.

A heel wedge test is similar to a very big (horse sized) hoof tester and puts pressure on the caudal heel structures. A toe wedge test places strain on the flexor tendons. For these, a rod or taped up hoof knife is placed under the heel (heel wedge) or toe (toe wedge) and the opposite foot lifted so the horse is standing on the rod. Some horses will not tolerate this; that may be a positive response.

A heel wedge test is similar to a very big (horse sized) hoof tester and puts pressure on the caudal heel structures. A toe wedge test places strain on the flexor tendons. For these, a rod or taped up hoof knife is placed under the heel (heel wedge) or toe (toe wedge) and the opposite foot lifted so the horse is standing on the rod. Some horses will not tolerate this; that may be a positive response.

Technology for lameness localization

There are now tools that can help identify more motion on a limb, making lameness exams more objective. Gait analysis (force plates) and devices to detect intralimb differences (lameness locator) exist to help us better determine the lame limb. These are not infallible and may come with so much information that they are overwhelming. Expect tools to continue to improve!

Visual lameness assessment in comparison to quantitative gait analysis data in horses. Equine Vet J. 2022;54:1076–1085.

Overall, between-and within-veterinarian agreement on lame limb was ‘good’, whereas agreement on lameness grade was ‘acceptable’ to ‘poor’. Quantitative data and subjective assessments correlated well, with minor though significant differences in the number of millimetres, equivalent to one lameness grade between veterinarians, and between assessment conditions. Differences between baseline assessment vs assessment following diagnostic analgesia suggest that addition of objective data can be beneficial to reduce expectation bias.

Diagnostics

While the history, standing exam, and active exam components can be done in any order, they should be completed prior to any local anesthesia or sedation. They are also generally done before any imaging diagnostics so that we can interpret the diagnostic findings (not all findings are associated with pain). However, if the horse is not amenable to the tests, imaging can be done without having a full lameness workup performed. The lameness evaluation could be performed after scintigraphy or radiographs, for instance.

Local blocks

Once we have identified the limb, we usually still need to confirm the region causing the pain. In most cases, we start at the hoof and move up. We numb each region and reassess the lameness at a trot. When the lameness goes away (or moves to the other limb), we know that the pain is coming from the region we just blocked. If we start too high, we numb large regions and are back to needing to localize further but now we have to wait for the local anesthesia to wear off. Knowledge of anatomy is again crucial!

If you have to guess, start with the assumption you have foot pain in the forelimbs and hock joint pain the hindlimbs. This means you might start with hock joint anesthesia, rather than a basisesamoid foot) block in the hindlimb.

This “subtraction” means it is important to move up the limb and to do so carefully so we don’t have a large region to evaluate (radiograph, ultrasound.).

This “subtraction” means it is important to move up the limb and to do so carefully so we don’t have a large region to evaluate (radiograph, ultrasound.).

Joint blocks above the foot are an exception to the bottom up process. We can skip around from joint to joint without going from distal to proximal. Local anesthesia injected into the joint generally numbs the joint and not much else as long as the horse is evaluated sooner rather than later (later on the local anesthetic leaches out and finds nerves). If the carpus is swollen on a racehorse, we may just radiograph it. However, if it is swollen but not painful or painful on flexion but not swollen (eg unclear diagnosis), we will often inject it with sterile local anesthetic to see if it is the source of pain. If this doesn’t resolve the pain, we can still do effective distal limb nerve blocks.

It is not uncommon for the horse to change which limb is lame during a series of blocks. Lameness is often bilateral as it is typically related to wear and tear and conformation issues. Once we numb the pain on one side, the horse can now show us the lesser pain on the other side. The veterinarian needs to carefully check which limb is showing pain at each step! In the example above, the horse would typically go lame on the right forelimb rather than becoming sound.

A response of 50% (50% improved after a local block) is pretty poor (aka not significant). A response of 100% is rare. Once we have the lameness improved to the point where we can no longer tell if things are getting better or not OR we have made significant improvement OR the horse is getting tired of needles, we will move to diagnostics such as ultrasound or radiographs.

Note: if you cannot see the lameness consistently, it will be hard to tell if your local blocks help. Try a different modality!

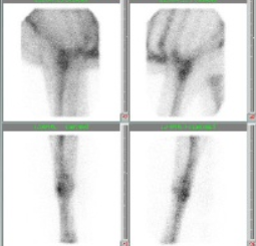

Scintigraphy (bone scans)

If the horse will not tolerate local blocks, if multiple limbs are lame or if the examination is pre-performance, it may be more effective to perform a bone scan. The horse is injected with a radioactive substance that collects at areas of remodeling bone (note: some scans soft tissue too). A large Geiger counter is used to monitor the radioactivity in the area of the body. We usually scan the front half, back half or entire body of the horse so a scan can cover a fair bit of the musculoskeletal system. The highlighted areas (radioactive hot spots) are then evaluated more closely, generally with radiographs.

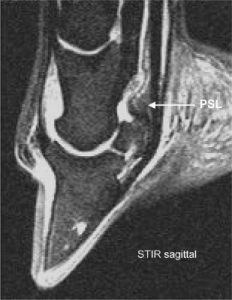

Imaging

Most lameness exams end with diagnostic imaging. CT and radiographs are best for bony structures; ultrasound for soft tissue. The foot has both and is best evaluated with MRI.

Key Takeaways

Lameness evaluations should be systematic to ensure all components are evaluated.

Very lame horses should not be trotted as they may have incomplete fractures.

Lameness exams generally include thorough palpation of the horse’s musculoskeletal system, passive exams (range of motion and hoof testers, etc), active exams (trotting, lunging, flexion tests) first. Once the area is localized to a limb, then local anesthesia is used to confirm the region is a source of pain. We hold off on diagnostics until we have the region localized to as small an area as is reasonably possible; ideally an area that will fit on a radiograph.

Ultrasound is key for soft tissue lesions while radiographs or CT are more useful for bony lesions. Keep in mind that there can be radiographic changes that do not cause lameness and lameness may be present without radiographic changes.

Scintigraphy is very useful when there are multiple areas of lameness or when horses are needle shy. MRI is very useful for the foot.

Resources

Malone lameness mindmap for download

Lameness Evaluation of the Athletic Horse, Vet Clin Equine 34 (2018) 181–191- thorough review

LAMENESS EXAMS: Evaluating the Lame Horse, AAEP. Date unknown – short and sweet synopsis

2018 Sporthorse lameness exam, TA Turner, FAEP- lots of great hints and explanation

Manual of clinical procedures in the horse. Eds: Costa & Paradis- Chs 27 and 28- how to’s with lots of pictures

Local anaesthetics for regional and intra-articular analgesia in the horse, Schumacher and Boone, Equine vet. Educ. (2021) 33 (3) 159-168- drug review and mythbusting.

Adams & Stashak’s Lameness in Horses, 6th edition; Ed: Baxter.

Lameness in the Horse; 2nd edition; Eds: Ross & Dyson.

Other examples

Withers vertical movement symmetry is useful for locating the primary lame limb in naturally occurring lameness. Equine Vet J. 2024;56:76–88.

Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Injury in the Sport Horse, Vet Clin Equine 34 (2018) 215–234- introductory level with pictures!