Equine joint disorders

Osteoarthritis

Pathophysiology

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a noninflammatory disorder of joints characterized by degeneration and loss of articular cartilage and development of new bone on joint surfaces and margins. It can also involve sclerosis of the subchondral bone. OA is a common response of joints to a variety of insults. In general, it is seen as a “wear and tear” phenomenon but can also occur secondary to osteochondrosis and sepsis. Once cartilage starts to break down, several factors are released into the synovial fluid that cause further inflammation and further cartilage breakdown.

Three main pathogenic mechanisms of osteoarthritis are proposed:

- Defective cartilage – flawed matrix fails under normal loading

- Normal forces damage healthy cartilage – injured chondrocytes release enzymes which cause cartilage damage and breakdown the proteoglycan network

- Increased stiffness of subchondral bone – microfractures heal with increased bone density; this leads to limited ability to absorb shock, pushing more load onto the cartilage

Synovitis contributes by increasing levels of inflammatory mediators. Synovitis can develop from trauma (eg a floating osteochondral fragment or direct trauma), release of inflammatory mediators from the cartilage, and infection.

Immune related changes (rheumatoid arthritis) are not seen in horses.

Key Takeaways

Cartilage helps absorb energy through creating a hydrated layer on top of the bone. Type II collagen, proteins and sugars create an environment that holds water (until it is damaged). Matrix metalloproteinases help clean up debris but create damage. Cartilage has very poor healing ability. Inflammation of the joint environment leads to arthritis – typically this is due to wear and tear and trauma.

Clinical signs

Clinical signs associated with OA include pain on movement, reduced range of motion, increased joint fluid (effusion), and changes in the synovial fluid (less viscous, lower hyaluronan content). Generally, OA affects older horses, horses with a heavy work background, those with osteochondrosis, and those with a history of joint infection.

- Reduced range of motion – pain, synovial effusion, synovial edema and periarticular fibrosis

- Effusion – increased levels of synovial fluid due to protein leakage

- Synovial fluid changes – high protein, low viscosity due to lower HA (hyaluronate) content

- Pain -due to synovial effusion, periosteal disruption from osteophytes, and potentially subchondral bone changes.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based upon localized lameness (clinical signs and/or local anesthesia) combined with radiographs and/or arthroscopy. Because OA starts as a cartilage disorder, not all lesions will be apparent radiographically.

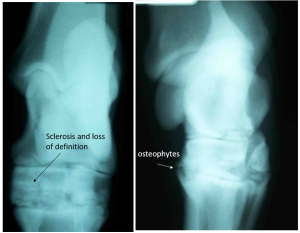

Radiographs will typically show new bone formation at the joint margins (osteophytes). Remodeling, loss of joint space and enthesiophyte production are also common.

Therapy

Cartilage does not heal well due to limited vascularity and potential for new cartilage growth.

At the present time we cannot resurface joints with normal cartilage. (Research is ongoing, funded by the NFL). Treatment is aimed at slowing the rate of cartilage breakdown.

Surgical therapy

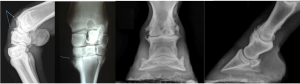

Arthroscopy is used for diagnosis, treatment and determining prognosis. If the joint is unstable, it must be stabilized for any treatment to be successful. It is important to remove or stabilize any loose fragments, and debride any cysts. Without surgery in cases with instability or sources of inflammatory mediators, medications won’t help.

Pastern and lower hock joints may also be “arthrodesed” or fused. This prevents motion and therefore prevents much of the pain associated. The pastern and lower hock are low motion joints. Fusing low motion joints is much easier than fusing high motion joints and does not affect other joints too severely. Fetlock and carpal joints are also occasionally arthrodesed. These are high motion joints so the fusion is much more complex and the complications greater.

Joint replacement is not commonly done in horses.

Medical management

Medical management is often used due to the cost of arthroscopy and arthrodesis. Choices depend on many factors, including value of the horse, current performance needs, future performance expectations, and the horse’s mental status (particularly if stall rest if recommended).

- NSAIDs are used to inhibit the inflammatory reaction; however, they may also interfere with the healing process and should be used judiciously until their full effects are understood. Motion is good for arthritic joints; NSAIDs do help with encouraging horses to move around.

- Corticosteroids may be injected into joints to relieve inflammation. At low concentrations they may be chondroprotective; however, prolonged use or high concentrations of corticosteroids will cause cartilage degeneration. Methylprednisolone is typically used in low motion joints while triamcinolone is used in high motion joints.

- Hyaluronan (HA) is frequently used in an attempt to provide cartilage structural materials, to increase the viscosity of the synovial fluid, and as a mild anti-inflammatory agent. An intravenous form (Legend®) is available and there is some experimental data to support its use. It is probably most effective in cases of acute synovitis. It may need to be given weekly for optimum effects.

- Polysulfonated glycosaminoglycan (PSGAG/ Adequan®) is composed principally of chondroitin sulfate, a component of cartilage. It is anti-inflammatory and is reported to stimulate the production of HA and to interfere with degradative enzymes. It may be given into the joint but ia administration greatly increases the risk of sepsis by decreasing the number of bacteria required to overwhelm the immune system. It is more often given intramuscularly, with a manufacturer’s recommendation of treatment every 4 days for 7 treatments.

- Oral supplements have also been developed; chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine are the two most common components. Chondroitin sulfate is similar to PSGAGs in its activity; however, many (all?) forms of chondroitin sulfate are not biologically available. Glucosamine is a precursor of cartilage proteoglycans and may have a number of anti-inflammatory activities. Experimental studies on these oral products are limited. The most convincing results have been with Cosequin®. Other common and perhaps useful brands are FlexFree®, Synoflex®, and MSM®(oral form of DMSO). Tetracyclines are inhibitors of MMPs but use of tetracyclines for arthritis may compound drug resistance issues. Nutraceuticals are NOT regulated by the FDA. Newer supplements with evidence of efficacy at pain relief include resveratrol (Equithrive), curcumin, cannabidiol oil, and avocado and soybean unsaponifiable oral supplement (found in some formulations of Cosequin®).

Note

Small animal studies do have more numbers so this is concerning. It may also reflect different metabolism and bioavailability between species:

From: A 2022 Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Enriched Therapeutic Diets and Nutraceuticals in Canine and Feline Osteoarthritis, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10384.

The efficacy assessment, associated to the level of quality of each trial, presented an evident clinical analgesic efficacy for omega-3-enriched diets, omega-3 supplements and cannabidiol (to a lesser degree). Our analyses showed a weak efficacy of collagen and a very marked non-effect of chondroitin glucosamine

nutraceuticals, which leads us to recommend that the latter products should no longer be recommended for pain management in canine and feline osteoarthritis.

- IRAP (interleukin receptor antagonist protein) competes with interleukin 1 for receptor binding in an attempt to decreased inflammation. Duration of binding is unknown.

- Platelet rich plasma and stem cells– trying to help with healing

- Anti nerve growth factor monoclonal antibodies –monthly injection of frunevetmab was useful in cats when repeated NSAIDs aren’t possible; still being evaluated in horses

- Free choice exercise helps keep joints mobile. Forced exercise can speed cartilage breakdown. Stall rest (if needed due to a particular therapy) can be very challenging for both horse and owner.

- Frequent trimming helps to keep the toes short (best breakover) and to keep the foot balanced.

- Rehabilitation/physical therapies may be recommended. Not all are scientifically proven. These therapies include hydrotherapy, ice, swimming, acupuncture, chiropractic, laser, electrical stimulation, therapeutic ultrasound, counterirritants, radiation, shockwave, massage, and heat.

- Nutrition/weight management. Weight control can be important. Supplements containing fatty acids may help decrease inflammation. Other supplements have variably shown anti-inflammatory and/or analgesic properties

Key Takeaways

Arthritis is common in horses and is usually due to wear and tear along with cartilage damage. Therapy is supportive

- NSAIDs

- Free choice exercise

- Frequent hoof trimming

- Supplements

Cartilage does not heal well. Joint supplements may be useful to prevent damage but quality varies.

Horse owners love fancy toys and “new” stuff (therapies).

Resources

Anatomy and radiography of the equine tarsus ibook

Large animal arthropathies, Merck. Updated 2022- good initial starting place

Current use of biologic therapies for musculoskeletal disease: A survey of board-certified equine specialists. Veterinary Surgery. 2022;51:557–567. – doesn’t mean they work….

Clinical insights: Recent developments in equine articular disease (2016–2018), Equine Veterinary Journal 50 (2018) 705–707

Pathophysiology of Osteoarthritis, CCE Jan/Feb 2009, pp 28-40

Management and Rehabilitation of Joint Disease in Sport Horses, Vet Clin Equine 34 (2018) 345–358- nice review of options

Equine shock wave therapy – where are we now? Equine Vet J. 2023;55:593–606. extensive literature review

Review of glucocorticoid therapy in horses: Intra-articular corticosteroids. Equine Vet Educ. 2023;35:327–336.

Evaluation of polysulfated glycosaminoglycan or sodium hyaluronan administered intra-articularly for treatment of horses with experimentally induced osteoarthritis. AJVR, 2009. DOI:10.2460/ajvr.70.2.203

Influence of trimming, hoof angle and shoeing on breakover duration in sound horses examined with hoof-mounted inertial sensors, Vet Rec 2021 – good explanation of breakover and how shoes impact it

Used in horses to describe the end of the stance phase: the period of time from when the heel is off the ground to the time when the toe is off the ground. This time window is prolonged with long toes and when a horse is shod. A longer breakover requires more joint motion.