Equine and Camelid Castration

Castration complications

With any surgery, there are standard complications, prevention steps and therapies to manage the complications

Hemorrhage

The testicular arteries can bleed well. Generally hemorrhage is controlled by innate clotting mechanisms, ligation or by pressure. However, it is almost impossible to apply effective pressure to the testicular arteries due to their location.

Many castrations are performed without ligation, using only crushing or other trauma to stimulate natural clotting. If the crush is not effective, hemorrhage can be significant and potentially fatal. To ensure a good crush, the emasculators need to be assembled and used correctly so that the crush is proximal on the cord and the cut is distal (nut to nut).

Typically emasculators are left in place for about 2 minutes. The hard crush is even more important than the time.

Prevention:

- Use open castration in older stallions so the cord can be managed directly. For larger stallions, an emasculator may not provide sufficient clotting if it is also trying to crush the other structures in the spermatic cord. These do better if the tunic is opened so the artery can be crushed separately and/or ligated.

- Ligatures can be used to control hemorrhage. Modified Miller’s knots are more effective than typical surgeon’s knots but both can be used successfully. Use material that will not cause long lasting irritation (eg not chromic gut). Ligatures are a great idea for donkeys (they like to bleed).

- Apply a hemostat to the cord so if bleeding is noted, the stump can be retrieved. Remove the hemostat before recovery!

- New emasculators can accidentally cut with the crushing part of the instrument. Many practitioners use the emasculators on rope a few times to dull the new metal in the crush section.

Treatment:

- If the surgery site is spurting blood or continuing a heavy bleed for an hour or more, reanesthetize the horse to find the artery and ligate it. Trying to find it in the standing animal just tends to make things worse.

Evisceration

Evisceration is a risk for any abdominal incisions or wounds. Intestines are slippery and can fit through small holes, particularly when the holes are ventral. Gravity works in most parts of the world and once the intestines start to slide out, the weight of the exposed intestines means more is likely to follow.

Prevention:

- Evisceration is difficult to prevent but those animals at risk should be identified. In particular, animals with inguinal hernias as foals or requiring cryptorchid surgery are at greater risk due to the larger size of the inguinal ring. Surgery at an equine hospital may be indicated. If not, bring supplies to manage escaping guts (sterile towels, vetwrap, suture and an assistant).

- If pursuing a cryptorchid testicle, limit stretch to the inguinal rings

Treatment:

- Reanesthetize the horse, clean any exposed tissues and put them back in the scrotal sac. Close the scrotum and refer

- Give iv antibiotics

Swelling

Swelling is always an issue with surgery and is always exacerbated in ventral locations such as the scrotal area. Swelling will occur with your surgery and is typically the most severe at 2-3 days postoperatively. After that time it should decrease gradually; continued swelling can indicate infection.

Hydrocoele is another complication that can lead to swelling. The tunic closes and peritoneal fluid fills the tunic giving the appearance that the horse has regrown his testicles.

Prevention

- NSAIDs should be part of your protocol both for analgesia and control of swelling.

- Exercise will help to minimize and reduce swelling by encouraging blood flow and lymphatic drainage.

Treatment:

- Swelling can typically be decreased by pressure, cold hosing, NSAIDs and exercise. As applying pressure in the area is tricky, that is typically not used.

- Cold hosing can be used if tolerated by the horse. The hose should not be directed up into the incisions since that would be aiming directly into the abdomen. Some horses will not tolerate cold hosing and it is not worth the risk to the owner or to the horse.

- Hydrocoele formation requires a second surgery to remove the sealed tunic

Facial nerve paralysis

Facial nerve paralysis occurs due to pressure on the nerve by the halter.

Prevention

- Remove the halter for recumbent anesthesia

Treatment

- Steroids can be given

- These usually resolve over time.

Radial nerve paralysis

Radial nerve paralysis occurs due to pressure on the radial nerve by the weight of the animals body. The down forelimb is typically affected.

Prevention:

- The down forelimb should be drawn forward so that it is in front of the body. This decreases the direct pressure on the nerve. Assign someone with the roles of making sure these things happen.

Treatment:

- Steroids

- Splint the limb so the horse can use it properly and doesn’t freak out. Freaked out horses have less brain function than normal.

Infection

Equine castrations are generally performed in a non-sterile environment with incisions left open; contamination is ensured. As long as the incisions stay open for drainage, infection doesn’t typically cause any problems. Issues with infection develop when drainage is impaired (as when the incisions close up too soon) or when chromic gut is used to ligate the vessels (since it is highly irritating). Gut is rarely used for castration now and other suture types seem much safer.

Infection at the castration site can potentially extend into the abdomen, causing peritonitis. Subclinical peritonitis definitely occurs after castration but rarely causes issues. Open castrations are potentially riskier in that they open the peritoneal cavity but closed castrations carry other risks.

Horses will typically develop scrotal swelling and go off feed if infection occurs.

Prevention:

- NSAIDs preoperatively and for 3 days to minimize swelling and ensure drainage

- Preoperative antibiotics (penicillin or ceftiofur)

- Make large incisions and stretch them before the horse wakes up

- Exercise the horse postoperatively to minimize swelling

Treatment:

- reopen incisions for drainage – this is relatively easy since just closed with a fibrin seal; push the edges apart with a gloved finger. No blades needed!

- antibiotics are NOT needed unless the horse continues to have a fever after drainage is provided

Poor healing

Poor healing is generally related to the factors listed above or to foreign material in the wound. If the incision continues to drain and does not close, it is likely that there is or was a foreign body in the wound.

Persistent infection can lead to spermatic cord infection.

Prevention

- avoid gut suture and long acting suture if ligatures are applied

- ensure good drainage

Treatment:

- General anesthesia and wound exploration is indicated.

- Spermatic cord infection can extend into the abdomen and require abdominal surgery to remove the infected cord.

Tetanus

Tetanus is uncommon but is life-threatening and horses are very sensitive to the bacterium. The vaccine works well and is highly protective. A booster is required for full protection.

- Tetanus vaccines are widely available; however, cold storage is necessary to maintain efficacy. Clients may not be aware of the careful handling and storage needed.

Prevention:

- Since castration is an elective procedure, horses should receive their initial tetanus toxoid at least two weeks prior to castration and can receive their booster shot at the time of castration. If a horse must be castrated in a shorter time frame, tetanus anti-toxin is recommended to provide immediate protection. Serum hepatitis is a risk with tetanus antitoxin.

Treatment:

- Intensive medical therapy is required. Tetanus is often fatal.

Stallion-like behavior

Horses may continue to act like stallions.

Prevention

- castrate before this behavior becomes ingrained

Treatment

- Time may help. This is NOT due to a retained epididymis!

*****************************************************************************************************

Key Takeaways

Drainage is key for postoperative management of the surgery site. To have adequate drainage, you need large holes and minimal swelling. To get minimal swelling horses need to exercise. Horses without pain relief will not exercise well. NSAIDs help them exercise and help with swelling. Horses should get about 3 days of NSAIDs postoperatively. One day of stall rest is often recommended but isn’t required.

If the drainage stops too soon, an infection is likely to develop. Drainage needs to happen. Generally recreating drainage just means using a gloved finger (with the horse sedated and twitched) to open the fibrin seal. Antibiotics are used only if the horse still has a fever after drainage.

Arterial bleeding, large swelling and things hanging out need veterinary attention. Large swelling is important, the others can be life threatening and need immediate attention.

It takes awhile for the horse to become infertile and to lose the mounting behavior of stallions. Keep him away from mares for about 6-8 weeks. Proud cut is not a thing.

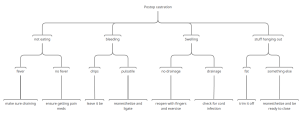

Postop complication flow chart – downloadable version

Challenges

Use your search powers (see the resource page), your new knowledge base and the resources below to try and find answers to the questions below.

- When is postoperative hemorrhage considered significant? What would the owner notice?

- Why is it important to not have the cord stretched out when applying the emasculators?

- What would you ligate a cord with? Hint: Gut is bad.

- If hemorrhage is significant, would you manage the colt standing or recumbent? What do you do? What if you can’t do that?

- What extra supplies should you bring with you for castrations, just in case of hemorrhage?

- ***********************************************************

- When is postoperative swelling excessive? What size fruit?

- What is the association between postoperative swelling and drainage?

- When and how do you open up the swelling to allow it to drain?

- Should the horse be on antibiotics? How do you know?

- How do you prevent issues with postoperative swelling?

- What is the time frame for swelling after surgery?

- ************************************************************

- What structures could come out the scrotal incisions besides intestines? What would an owner be able to identify to tell you about?

- Are certain breeds, ages or conditions more prone to evisceration (eventeration)? What would you do to prevent issues?

- What is the time frame for risk of evisceration after castration?

- The animal stands up and is eviscerating. Do you manage him standing or recumbent? What do you do? What if you can’t do that?

- What extra supplies should you bring with you for castrations, just in case of evisceration?

- **********************************************************

- What is schirrous cord/ Why does it develop?

- Are certain breeds, ages or conditions more prone to schirrous cord? What would you do to prevent it?

- What is the time frame for when schirrous cord is likely to happen after castration?

- How do you diagnose schirrous cord?

- How do you treat schirrous cord? What if you can’t do that?

- What extra supplies should you bring with you for castrations, just in case?

- *********************************************************

- When does penile trauma happen and what is needed for treatment?

- When does hydrocoele happen and what is needed for treatment?

- What does peritonitis look like and what is the treatment?

Exercises

Try these cases to see if you agree with my recommendations:

Resources

A review of prevention and management of castration complications. Equine Vet Educ. 2024;36:97–106.

A prospective multicentre survey of complications associated with equine castration to facilitate clinical audit. EVJ 2019- spoiler alert – they didn’t find many complications. And the Brits are way ahead of us with proper analgesia.

How to treat castration complications in the field – video CE, 2019 article

How I manage castration complications in the field, AAEP 2015 p 224.

Incidence, management and outcome castration complications, JAVMA 2013

Open standing castration in Hong Kong: prevalence and severity of complications, EVJ 2018