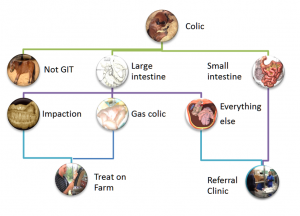

Equine Colic

Field diagnostics

The goal of field diagnostics is to determine where on the flow chart this case is likely positioned. Not all diagnostics are required in most cases. Clinical signs, physical exam findings and nasogastric intubation to check for reflux are key.

While colic typically refers to signs of GI issues, it is important to remember that not all colics are due to GI lesions. Thoracic pain from pleuritis, foot pain from laminitis, muscle pain myopathies, ureteral stones, biliary stones and abnormal behavior from rabies are commonly first identified as “colic”.

History

History can be helpful, particularly with recurrent colics. Enterolithiasis is associated with west coast living and is more likely if another horse on the farm has had an enterolith. Sand impactions are more common in certain areas of the country, particularly when horses feed is placed on the ground. Travel may increase the risk of impactions or pleuritis. Limited dental care may point toward impactions or fecoliths due to difficulty chewing. Large colon volvulus is more common in postpartum broodmares. Right dorsal colitis is associated with NSAID administration.

Signalment predilections also exist, particularly for Arabs, Friesians, broodmares, stallions, old horses, neonates and miniature horses.

Clinical Signs

Horses with colic will look at their side, kick at their belly, act agitated, lie down and/or roll. Many will be sweating due to pain. If they have been rolling, you may see hay or straw on their backs or in their manes. Many that have been rolling will have abrasions on their head or limbs. Commonly, horses will stretch out and pass small amounts of urine. Many owners will call you about the possibility of a urinary tract infection. Horses with mild colic may just not eat well and exhibit no other signs. Horses should pass at 6-8 piles of manure per day. Limited (<3) manure piles or dry, small fecal balls can indicate poor motility.

Donkeys will show less signs of overt colic. Depression, anorexia and weight loss are the most common signs. A donkey that is depressed for more than 12 hours should be evaluated closely.

Most donkeys undergoing colic surgery also had non-GI complications, the most common of which was hyperlipemia.

Physical examination

Physical examination findings can help determine the severity and type (medical vs surgical) of colic. Fever is rarely associated with surgical conditions. A normal to slightly elevated heart rate (40-60bpm) is more commonly associated with large intestinal or milder colics. Very high heart rates (80-100bpm) are associated with dehydration and shock. Small intestinal and surgical colics are more likely to have such high heart rates and to need fluid resuscitation. Elevated respiratory rates can be pain or indicate pleuritis, pneumonia or diaphragmatic hernias. Dehydration is evidenced by tacky mucous membranes and prolonged refill times as well as elevated heart rates. Toxic lines (red lines next to teeth) suggest endotoxemia. Bloat generally indicates a large colon issue. Weight loss can be seen with some forms of chronic colic.

Sedation for diagnostics

Most horses will need sedation before nasogastric intubation or more invasive diagnostics. The goal is to sedate sufficiently to be safe but not so heavily or for such a long duration that the sedation interferes with monitoring or worsens the horse’s systemic status.

Xylazine is the first choice for most colics. It provides both sedation and pain relief for about 15 minutes. It can last 20-30 minutes when combined with butorphanol.

Detomidine or detomidine/butorphanol may be used if the horse needs to be transported to a referral center. The center should be notified as the combination can be strong enough to make a surgical horse look less in need of surgery.

Acepromazine should not be used due to its hypotensive effects.

Nasogastric intubation

Intubation is warranted in almost all colics. Passing a stomach tube can relieve fluid build up in the stomach. Since horses cannot vomit, this can be lifesaving. Without intubation, the stomach may rupture.

Rectal palpation

Rectal palpation may be needed in cases of recurrent colic. It is risky to the person palpating (kick injury) and to the horse (rectal tears)

A systematic approach is recommended.

Ventral

The pelvic flexure is the most common site of impactions. A normal pelvic flexure should be palpable ventral to the rectum but only as a soft bag of intestines. It should be smooth (not sacculated) and not readily palpable. Impactions make the pelvic flexure easier to feel and range from doughy oatmeal to firm but indentable structures. Gas will not be indentable and usually gives a more rounded feel. Displacements may mean you can feel sacculations; more often, the colon is not where it belongs. A volvulus may result in a very distended colon that makes it hard to get your arm very far into the rectum.

The small colon may also be present in line with the rectum or slightly ventral. It generally doesn’t feel like much but a small colon impaction will result in a tube of feces that has wide bands. This tube often runs across the caudal abdomen. Expect a doughy balloon.

Left

The spleen should be next to the left body wall and the nephrosplenic space clear. It may not be possible to feel the nephrosplenic space if your arm isn’t long enough relative to the horse’s length. If the spleen is deviated medially, consider a nephrosplenic entrapment more possible. If you can’t feel the space or think colon is in the space, ultrasound can help confirm a displacement.

In a stallion, check the left inguinal ring to ensure no intestines are passing it through it.

Dorsal

Check the aorta and iliac arteries for pulsation. Clots in an artery can lead to ischemic pain that can mimic colic.

Check the sub lumbar lymph nodes for enlargement.

Right

The cecum and ileocecal area are on the right. The ileum should not be palpable nor should any SI be found in the other quadrants. The cecum should be palpable but not distinct. An obvious cecum (gas or ingesta filled) is abnormal.

In a stallion, check the right inguinal ring to ensure no intestines are passing through it.

Other

It would be unusual to feel small intestine or to not feel much at all. The latter may indicate displacement or herniation. A feeling of crepitus, gas bubbles or rough surfaces likely indicates a rupture of a viscus. Confirm with abdominocentesis.

Abdominal Ultrasound

The FLASH technique has been developed for quick scans in the field; more intensive ultrasound evaluations are usually done in a clinic.

Lactate analysis

Portable lactate analyzers are making it much easier to measure and monitor lactate in colics. While most studies have been performed in referral institutions, a high lactate likely indicates a need for hospitalization and intensive therapy, along with a poorer prognosis

Abdominal fluid analysis

Abdominocentesis can be used to help differentiate between surgical and non-surgical colics as well as prognosticate. The tap is performed at the most ventral area of the abdomen or where a fluid pocket is identified ultrasonographically.

Normal abdominal fluid is straw-colored and clear (you should be able to read newspaper print through it), with reported reference ranges of: <2.0g/dL (measured biochemically) or <2.5g/dL (measured via refractometer) for total protein (TP), <5,000-10,000 total nucleated cells/uL (NCC), and a lactate level of <2.0mmol/L with a ratio of peritoneal to plasma fluid lactate of <1:1. Changes in TP concentration or increased number of NCC or erythrocytes will change the appearance of the fluid to cloudy, dark yellow, orange or red. Elevated lactate levels can also confirm the presence of ischemic bowel.

Risks of abdominocentesis include a splenic tap, an enterocentesis or a tear of the intestines. Splenic taps resolve on their own; they just complicate diagnostics. Enterocentesis (gut tap) can be mistaken for ruptured intestines since bacteria are present; this can be differentiated from true peritonitis by the lack of white blood cells. Intestinal trauma is more likely in foals and when taps are performed using needles rather than teat cannulas.

Key Takeaways

Abdominal fluid colors and differentials to consider

- Clear yellow –

- normal fluid

- normal fluid, abnormal belly

- horses with bowel through a hernial ring (fluid is sequestered) or with a thickened bowel wall can have normal fluid

- Clear yellow orange – check protein levels

- inflammatory bowel disease

- Cloudy yellow or yellow orange- increased cell counts

- peritonitis

- Cloudy yellow-green –

- bowel rupture

- check for wbc cells + plant material or bacteria

- Reddish (serosanguinous)

- dead bowel

- Bright Red

- splenic tap or hemoabdomen

Non-strangulating obstruction: Most cases will have normal peritoneal fluid; however, in some cases the fluid can become slightly turbid with a NCC 5,000-15,000cells/uL and TP <2.5g/dL. Cytology may reveal an increase in segmented neutrophils.

Non-strangulating obstruction: Most cases will have normal peritoneal fluid; however, in some cases the fluid can become slightly turbid with a NCC 5,000-15,000cells/uL and TP <2.5g/dL. Cytology may reveal an increase in segmented neutrophils.

Strangulating Obstruction: Exudative. Dark yellow to serosanguineous. Elevated NCC (values from 10,000-150,000 cells/uL), TP, and lactate levels (>2.8mmol/L). High number of RBC and if the sample is spun down in a centrifuge, it remains blood tinged indicating that it is not iatrogenic blood contamination. Often cytology shows 90-95% neutrophils with a high proportion of degenerative neutrophils and erythrophagia.

Strangulating Obstruction: Exudative. Dark yellow to serosanguineous. Elevated NCC (values from 10,000-150,000 cells/uL), TP, and lactate levels (>2.8mmol/L). High number of RBC and if the sample is spun down in a centrifuge, it remains blood tinged indicating that it is not iatrogenic blood contamination. Often cytology shows 90-95% neutrophils with a high proportion of degenerative neutrophils and erythrophagia.

Infarction (dead bowel): Dark yellow to reddish brown. Elevated NCC (>150,000 cells/uL), TP, and lactate levels (>2.8mmol/L). These changes typically occur later in disease progression and have fewer RBCs than seen with strangulating obstructions.

Inflammatory (colitis/enteritis): Yellow to orange (rarely serosanguineous) with a very high total protein (>4.5g/dL) and normal to elevated nucleated cell count. Protein levels are high due to leakage through the damaged gut.

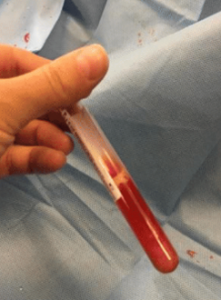

Septic Peritonitis: Exudative. Dark yellow, orange, serosanguineous, or white with an elevated TP and NCC (>150,000 cells/uL). Cytology shows increased percentage of degenerative neutrophils and there may be evidence of a single bacterial agent suggestive of primary peritonitis. (What is the most common bacteria associated with primary peritonitis?). Notice in the first image the large number of WBC at the bottom of the tube. The second image is from the worst case of peritonitis I have seen.

Septic Peritonitis: Exudative. Dark yellow, orange, serosanguineous, or white with an elevated TP and NCC (>150,000 cells/uL). Cytology shows increased percentage of degenerative neutrophils and there may be evidence of a single bacterial agent suggestive of primary peritonitis. (What is the most common bacteria associated with primary peritonitis?). Notice in the first image the large number of WBC at the bottom of the tube. The second image is from the worst case of peritonitis I have seen.

GI Rupture: Exudative. Dark yellow to brown or green tinged; may also appear serosanguineous. Elevated NCC, TP, and neutrophil to monocyte ratio. Often find a mixed population of intra- and extracellular bacteria as well as plant material. The combination of bacteria and white blood cells differentiates it from enterocentesis (gut tap).

GI Rupture: Exudative. Dark yellow to brown or green tinged; may also appear serosanguineous. Elevated NCC, TP, and neutrophil to monocyte ratio. Often find a mixed population of intra- and extracellular bacteria as well as plant material. The combination of bacteria and white blood cells differentiates it from enterocentesis (gut tap).

Horses with strangulating lesions or significant pathology may still have normal abdominal fluid!

Key Takeaways

- SI obstruction leads to reflux. LI obstruction leads to bloat. Usually.

- High heart rates mean dehydration and shock. Refer.

- Always pass a stomach tube. Reflux suggests a SI lesion. Refer

- Serosanguinous abdominal fluid often indicates dead bowel. Refer

- Rectals can be dangerous to both horse and veterinarian. Only do if safe and necessary. Palpable changes may include distension (gas or impaction) or displacement (spleen, guts).

Resources

Updates on Diagnosis and Management of Colic in the Field and Criteria for Referral, 2023 VCNA- good review of rectal palpation and criteria for referral

Abdominal Sonographic Evaluation In the Field, at the Hospital, and After Surgery. 2023 VCNA

Management of colic in field, 2021 VCNA

Equine peritoneal fluid cytology, Eclinpath, Cornell

Practical_Guide_To_Equine_Colic_Abdominocentesis. Ch 10

Peritoneal fluid analysis for the differentiation of medical and surgical colic in horses, In practice, 2004

Manual of clinical procedures in the horse

mineral concretion or calculus formed anywhere in the gastrointestinal system

endotoxins (from dead gram neg bacterial cell walls) leak into the bloodstream of certain horses with colic, causing severe illness

reddish color due to blood contamination