Large animal wounds

Bone damage

Wounds leading to long bone fractures, joint dislocations, collateral ligament damage, nerve damage, and/or flexor tendon transection will lead to limb instability. Horses that cannot bear weight on a limb or that have limb angulation should be sedated, splinted and referred. See Emergency Orthopedics

Fractures of smaller bones

Direct damage to the smaller bones is possible. Fractures of the splint bones (metacarpus/metatarsus II and IV) and the fibula are relatively common with wounds. Radiographs are recommended, particularly in horses with significant lameness or wounds on the palmaro/plantarolateral or palmaro/plantaromedial aspects of the cannon bone.

Sequestration

Sequestra are pieces of dead bone that develop over 2-3 weeks and lead to persistent draining tracts.

A superficial layer of cortical bone can die off with wounding. This may be related to direct damage, contamination or a combination of factors. The dead bone detaches from the parent bone but is often trapped in the wound as a sequestra. These are seen as foreign bodies by the immune system. The immune system attempts to destroy the dead bone through lysosomal actions and, when that isn’t successful, then tries to wall the dead bone off with additional bone formation (involucrum). Due to the dead fragment, the wound does not completely fill with granulation tissue.

Note: we consider this osteitis, NOT osteomyelitis. The infection, if present, is superficial.

To find the sequestrum, it is often necessary to take multiple radiographs at slightly different angles to identify the slim bone fragment.

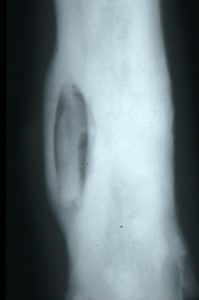

In the case in the image, the calf’s limb was caught in a metal feeder. The dead bone (sequestrum) is surrounded by new bone (involucrum). The draining tract through the bone is the cloaca.

To prevent sequestrum formation, the wound should be kept moist and covered. The surface of the bone can be rasped to debride the top layer of contamination.

If the wound is otherwise doing well, the skin may heal but with a persistent draining tract. In other situations, it is obvious that part of the wound is not being covered by pink granulation tissue. Sequestration should be suspected if the wound continues to drain after 2 weeks.

Radiographs are used to identify the location and size of the sequestrum. The optimum time to evaluate a wound for sequestration is 2-3 weeks after injury. Before that time, it is not radiographically apparent. After that time, it may be harder to remove as more bone is laid down over the top of the dead fragment as the involucrum.

Surgical removal is required. Occasionally this may be done standing; other cases may require general anesthesia. The process will set back the wound healing process but it should proceed more smoothly this time. Owners will likely be frustrated.

Foreign bodies and infected or damaged tendons and ligaments can also lead to poor granulation tissue coverage and draining tracts. These also require further surgery to remove the foreign bodies and/or debride structures.

Key Takeaways

If you can see the bone, sequestration is a risk. Clean the surface by rasping and keep the wound moist. If granulation tissue doesn’t develop, bone is likely dead/dying.

If the wound heals 90% of the way but never gets fully healed, take radiographs.

Taking radiographs at 2 weeks is optimum for sequestrum identification. Sequestra are typically visible by then and are easier to remove.

Resources

Wound Management: Wounds with Special Challenges, VCNA Vol.34(3), pp.511-538, 2018

Osseous sequestration in alpacas and llamas: 36 cases (1999–2010), JAVMA Vol.243(3), pp.430-6, 2013