FA GI Diagnostics & GI Surgery Principles

How to – Standing GI Surgery

Indications

Standing GI surgery is a common field and referral procedure in cattle. Right flank approaches allow for abdominal exploratory, correction of abomasal displacements, typhlotomy and other procedures. Left flank approaches allow for rumenotomy, Csection and correction of LDAs.

Relevant anatomy

The musculature of the flank includes the exterior abdominal oblique, the internal abdominal oblique and the transversus. Each muscle layer becomes progressively thinner, with the transversus muscle usually being a fibrous sheath. There is no strength layer in the flank – muscles tear easily.

The nerve sensation to the flank muscles comes from the spinal nerves T13, L1 and L2. These can be blocked using local infiltration or paravertebral blocks. The peritoneum is difficult to numb.

The vasculature supply for the area is robust, leading to good healing.

The abdominal cavity is under negative pressure normally. When the peritoneum is opened, air flows in,c creating an audible noise. If air does not flow in, the main differentials are recent abdominal surgery or a ruptured viscus (leaking air).

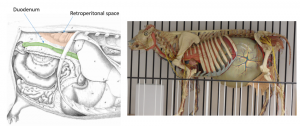

The retroperitoneal space is relatively large in cattle. If an incision is made too dorsally, this space will be visible. The surgeon may feel they have encountered lots of adhesions. In the peritoneal cavity, the duodenum should be directly visible in the incision on the right and the rumen on the left.

Preoperative management

Food restrictions: NA

NSAIDs/analgesics: Recommended preoperatively. Flunixin meglumine 1.1-2.2 mg/kg iv is standard.

Antibiotics: Recommended. As cows can wall off infection, there can be surprises inside. If milking, ceftiofur 2.2 mg/kg im is standard. In beef or non-lactating cattle, other options do exist. Remember: the label dose of procaine penicillin is ineffective!

Local blocks: A line block, inverted L or paravertebral are all reasonable options.

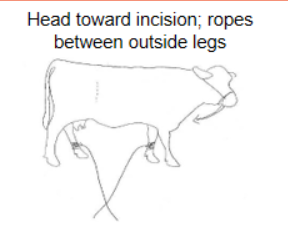

Position/preparation: Healthy cows tolerate standing surgery very well. Many do not need sedation but will do fine with just a local block. If the cow is hypocalcemic or if the mesentery is stretched (by lesion or by exposure for evaluation), the cow may lie down. If this is a concern, we try to make it more likely that she will land incision side up.

Place ropes on the far legs and tie her head toward the incision. If she starts to lie down, nonsurgical personnel pull on the ropes and pull her legs out from under her. With the head tied in this direction, she is also more likely to fold that way and stay incision side up.

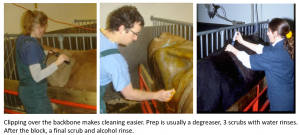

Place ropes on the far legs and tie her head toward the incision. If she starts to lie down, nonsurgical personnel pull on the ropes and pull her legs out from under her. With the head tied in this direction, she is also more likely to fold that way and stay incision side up.The flank is clipped, scrubbed, and the block performed.

Usually the most challenging part of the procedure is the block. Cows do not like needles. Options include a tail jack, towel over the face, or sedation. Or all 3. The EasyBossE is another humane restraint device that may help.

A sterile paper drape can be clipped to the skin of the back using towel clamps. This is a cheap way to keep things clean and to minimize suture contamination. Gowns are less useful than the drape…

Surgeons should wear gloves and sterile sleeves. Double gloves are useful if a contaminated procedure is expected as the top layer of gloves can be removed quickly. Caps and masks are recommended but not often worn. Gowns are not helpful for sterility unless water impermeable but do help keep the surgeon a bit cleaner and warmer.

Surgery Supplies:

- Standard surgery pack

- Sterile sleeves for internal palpation

- Scalpel blade and handle

- 2 or 3 absorbable suture material for muscle closure

- 3+ nonabsorbable suture material for skin closure

- Biopsy instruments and formalin- optional

- DA simplex – long flexible tubing attached to a 10ga needle for viscus decompression -optional

Surgical procedure

After the cow is prepped, blocked and draped, a large window is cut in the drape. This window should be as large as possible without exposing any hair or facilities (side gate etc).

A vertical incision is made, typically in the center of the paralumbar fossa, starting at least 10 cm below the transverse processes and extending about 20 cm. [If you are struggling later, make the incision longer. It heals side to side, not end to end. Go too high and you will see kidneys. Lower makes access to the abomasum much easier.] Remember to keep your blade on the skin, using your other hand to spread the incision edges to see how deep you are. You generally won’t be deep enough. Think about all the muscle underneath you and be bold.

Incise through the external abdominal oblique.

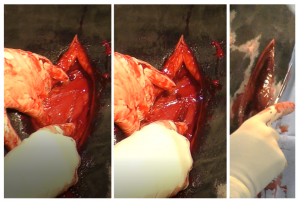

To safely and quickly cut through each muscle layer:

- First determine how thick a muscle is by starting with a 3 cm incision at the top, shaving (cutting in thin layers in the same area) until you reach the white fascia layer.

- Once the fascia is seen (and you can slide a finger between the muscles), slide a set of long thumb forceps under the external abdominal oblique and above the fascia (it should go easily). Slide them down as far as possible and turn these so the tongs are flat, creating a “groove director” between them.

- Use the center of the forceps as a “groove director” and as a guide for your incision. If the cow moves, the thumb forceps will help protect the deeper layers from accidental incision and enable you to incise without worry as long as you keep your blade flat.

Incise the internal abdominal oblique (it will be thinner) using the same technique. Tent the transversus and cut with scissors or with the blade turned so the cutting edge is facing the surgeon. This is to ensure you don’t cut too deeply.

Incise the peritoneum, listening to see if air rushes in. Extend the peritoneal opening to allow easy palpation with one arm.

Place a sterile sleeve on your left arm (regardless of whether left or right handed). If it is large for your hand, add a sterile glove over the top to improve your palpation skills. Generally this is one size larger than your normal glove size. **REMOVE ANY HEMOSTATS USED FOR BLEEDERS**. Finding these in the belly is somewhat challenging.

Exploration should be done from clean to potentially (or known) contaminated regions. In cattle, the riskiest areas are by the reticulum (hardware disease), liver (abscesses) and abomasum (perforated ulcers). As all of these are cranioventral, we typically start caudodorsal and to the left, followed by caudoventral, craniodorsal and finally, cranioventral.

A prophylactic omentopexy is often performed at the conclusion of right flank procedures, even if not for abomasal displacement.

Closure

There is no need to close the peritoneum or include it in your closure. Suturing the peritoneum does increase adhesions in cattle. This can be useful in some surgeries; not desirable in others.

The internal abdominal oblique and transversus can be closed as a unit, using 2 chromic gut or similar suture in simple continuous pattern. High levels of air in the abdomen can lead to pain so the cows are often “burped” during closure. Start the closure at the ventral aspect of the muscle layers. As you reach the top, preplace the final sutures and the first throw but do not tighten. Push in on the cow’s flank to push the gas out. With the flank still shoved in, tighten the last throw and then tie.

The external abdominal oblique is typically closed by itself in a similar fashion but no burping required.

Some practitioners close all muscles together. Because muscles tear easily, that can be risky if the cow falls during the healing period.

The skin is closed with a Ford Interlocking pattern using nonabsorbable suture in size 3 or 5. This is a great time to finish with an Aberdeen knot. A cruciate or simple interrupted suture is often placed at the ventral aspect. This can be removed to allow drainage if seroma or abscess develops.

Hint: Suturing cow hide is like sewing leather. If you try to insert your needle at an angle to the skin, you make it harder. If the needle is perpendicular to the skin, it goes in easier. The easiest way to do this is the change how you hold the skin. Make the skin perpendicular to the needle. It also helps to “choke up” on the needle – grasp it closer to the tip.

Postoperative care

- Suture removal in 10-14 days

- Monitor the cow for any signs of infection or peritonitis

- Consider rumen transfaunation if available

Complications

- Cow decides on recumbent surgery

- always good to expect this, especially with Jerseys

- Incisional dehiscence (rare)

- Incisional infection (common)

- Peritonitis

Videos

Resources

PRACTICAL APPROACHES TO ON-FARM BOVINE SURGERY, Dr. Gordon Atkins, University of Calgary Veterinary Medicine

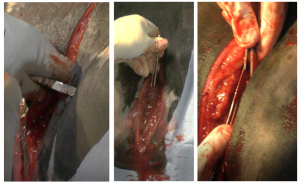

incision into the cecum

traumatic reticuloperitonitis; foreign objects poke through the reticulum