Large animal wounds

Wound healing overview

Wound healing follows similar processes across species. While it is a complex and continuous process, we typically divide wound healing into 3-5 somewhat arbitrary phases:

- Inflammation and debridement

- Repair

- Maturation

Starting day 0: Inflammation and debridement

Pathophysiology

As soon as wounding occurs, the body responds. Blood and fibrin flow into the wound and slow or stop bleeding by creating a clot (5-15 minutes). This clot also serves as a scaffold for the repair processes. Phagocytic cells enter the wound (24 hours – 2 weeks) and remove foreign matter and bacteria. Non-viable areas are walled off and/or separated from the living tissue.

Clinical signs

Bleeding stops, scabs form. Exudate and/or oozing are visible in contaminated wounds. The wound will increase in diameter. Inflammation will be evident as heat, swelling, and/or redness.

Therapeutic goals

Veterinarian debridement of contaminated wounds minimizes the duration of this phase. Sharp (scalpel) debridement is used when it is safe. Chemical or bandage debridement is used when sharp debridement might enter joints, tendon sheaths or body cavities or when sharp debridement may impact future function (eyelids, urethra, etc).

Starting day 4-5: Repair (proliferation/granulation)

Pathophysiology

This phase starts when blood clots, infection and debris have been cleared. This stage is identified by the formation of granulation tissue. Granulation tissue is comprised of fibroblasts, macrophages, and lots of vascular endothelial cells. Granulation tissue provides a surface for epithelialization, prevents infection from entering deeper tissues and is required for wound contraction. Repair requires an effective blood supply; angiogenesis (formation of new vessels) is critical.

Clinical signs

Pink granulation tissue appears about day 5 (4 in ruminants) and will rapidly expand across healthy tissues. Oozing may continue. Areas of necrotic tissue and/or bone may become evident. Devitalized skin will be leathery and dark. Devitalized bone and tendon will stay white without evidence of granulation tissue formation. The wound bleeds easily if damaged. Suture will not hold. As fibroblasts enter, the wound continues to enlarge due to contraction at the edges.

Therapeutic goals

Enable granulation tissue to cover the wound. This can be sped by creating a moist, hypoxic environment (bandaging). Hypoxia encourages angiogenesis.

Starting day 10: Maturation (epithelialization and contraction)

Pathophysiology

At the start of this phase, a light pink rim can be observed at the wound margins. This rim is due to the formation of new epithelial cells. These cells will migrate across the wound and cover it unless 1) the wound isn’t flat (exuberant granulation tissue) or 2) the forces pulling the wound apart are too strong (limited loose skin). This phase can be very slow; epithelialization occurs at a top speed of 1.5 mm/10 days.

Strength of the wound repair increases due to fibroplasia. Myofibroblasts try to close the wound.

Clinical signs

Granulation tissue should be more mature – the wound should be flat and the granulation tissue becoming either pale or more uniformly dark red. The wound should not be oozing. If the granulation tissue is bumpy or bright pink, it is still in the repair phase. The light pink epithelial band should continue to grow towards the center of the wound. The wound should eventually be covered by epithelial cells. With time, the area becomes more fibroblastic (scarred) and hair may regrow.

For wounds over the torso, wounds get smaller starting about day 6 due to effects of myofibroblasts. Eventually the wound is closed and a scar forms. Limb wounds do not usually get much smaller via myofibroblastic work.

Therapeutic goals

The goal is to allow the epithelial cells to migrate as easily as possible. This means minimizing their destruction (by toxic topical agents) and by minimizing the distance they need to move (minimizing exuberant granulation tissue and potentially using relief incisions or skin grafts). Adding islands of skin for additional epithelialization (skin grafts) may be necessary in bigger limb wounds.

Healing types

The process is affected by the type of wound healing:

- primary (first intention) healing

- secondary (second intention) healing

- delayed primary healing

Primary healing

Clean wounds that are sutured and do not fall apart fit this category. The wound requires minimal natural debridement, granulation tissue formation or epithelial migration. Generally the wound heals by about 10 days (suture removal time).

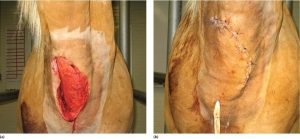

Secondary healing

Wounds that are not closed. The steps above will be visible. Contaminated wounds and wounds with limited vascular supply will move more slowly through the process. Bandaging will lengthen the maturation phase. Wound size and contamination dictate how long this phase takes. Most will take at least two months.

Delayed primary closure

Wounds that are closed at a later date would be in this category. Typically, this includes wounds that are cleaned before closure is attempted. This is generally not performed in horse limbs as the level of wound expansion means closure becomes harder over time.

Resources

Wound healing in animals: a review of physiology and clinical evaluation. Veterinary dermatology, 2022, Vol.33 (1), p.91-e27

Nonhealing wounds of the equine limb. VCNA Equine practice 2018. 34(3):539-555

The Pathophysiology of Wound Repair. VCNA Equine practice 2005. 21(1):1-13

Handbook of equine wound management. Derek Knottenbelt, 2003.

proud flesh; granulation tissue that doesn't stop when the wound is filled but continues to grow into a mound