Female urogenital surgery

Vaginal prolapses

Vaginal prolapses are relatively common in food and fiber species, being most predominant in late gestation cattle, sheep and pigs due to increased abdominal pressure from the growing fetus. Older animals are more commonly affected. Prolapses are occasionally seen in beef heifers and at other stages of gestation.

Besides pregnancy, other risk factors include coughing, obesity, hormonal changes (including estrogenic feeds), trauma, short tail docks (sheep) and previous vaginal prolapses. Poor quality roughage and severe cold weather have been implicated. Breed predispositions occur with Herefords, Shorthorn cattle and llamas. Bos indicus breeds are more prone to a variant involving cervical prolapse.

Differentials include rectal and uterine prolapses. Uterine prolapses are covered with caruncles (“bread loaf” appearance). Animals may develop secondary prolapses (eg rectal prolapse from straining due to a vaginal prolapse).

Recurrence of vaginal prolapses is common.

Vaginal prolapses do not lead to uterine prolapses.

Therapy

The 3 R’s apply to fixing vaginal prolapses:

- Replace

- Retain

- [Prevent] recurrence

In the middle of that we try to deliver a live neonate.

Epidural anesthesia is indicated. Pudendal nerve blocks may help.

If the prolapsed tissue isn’t damaged, osmotic agents (hypertonic saline, hypertonic dextrose*) are used to reduce swelling and return the tissue to its normal position. The bladder is sometimes involved in the prolapse; emptying it can help with replacement. To do this, lift the prolapse toward the anus.

*we can create a sugar or salt paste, as well, but there is some concern that sugar and salt granules can directly damage the mucosa.

If the tissue is damaged or the swelling just won’t go back in, we can perform surgery to remove the damaged area, using either mucosal resection/anastomosis or a complete amputation and anastomosis.

Retention can be via:

- closing the vulva lips and preventing anything from extruding

- creating scar tissue to hold the vagina in position (pexy)

- removing the vaginal tissue to minimize the amount that can prolapse

As the animals are often pregnant, it is necessary to choose a technique that will not cause delivery issues. This can vary depending upon accuracy of due dates and level of calving supervision (see notes in the techniques listed below).

Standing sedation (if needed) and local anesthetic blocks are effective for these procedures. A pudendal nerve block can help with relaxing the vagina as well as providing analgesia if pexy techniques are performed (see page 22 in the linked reference).

Sheep are often treated with a commercial retention device, rather than surgery.

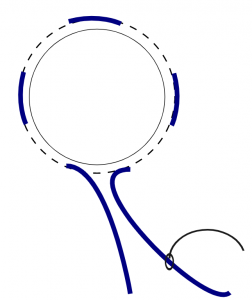

Buhner stitch

The Buhner stitch is basically a “purse string suture” around the vulva, designed to hold everything in place.

A large Buhner needle is used to place umbilical tape deeply around the vulva. This is tightened until only 1-2 fingers can fit into the vulva. The umbilical tape must be removed prior to parturition or delivery will result in trauma to mom and baby. Cattle do develop signs of impending parturition that can be used as markers (milk in the udder, relaxed tail head, etc) to tell the manager when to remove the Buhner stitch. A Buhner stitch would not be a good option for a beef cow that calves unsupervised on pasture.

Variations of the Buhner include horizontal mattress sutures (easier to put in but less physiological in the type of closure) and bootlace patterns (suture loops on each side of the vulva are placed for umbilical tape to be threaded through; this variant can be opened and reclosed without surgery but is not as strong).

Minchev Pexy

The Minchev procedure creates an adhesion between the vagina and the sacrosciatic ligament (in the pelvis) to prevent prolapse. This technique keeps the vagina open and does not need to be removed for delivery. It is important to avoid the rectum when performing the pexy. Typically we place two Minchev sutures to distribute forces. The sutures should be on the same side of the cow to avoid squeezing the rectum between them. “Buttons” or stents are used to distribute pressure; without such stents the suture tends to cut through the tissue. Sutures are left in place until after calving.

A Minchev can be challenging to perform if the tissue is very swollen. If you can get the prolapse back where it belongs, the swelling goes down. It may help to place a Buhner stitch initially and then replace it with a Minchev pexy the following day.

Cervicopexy

Since the prolapse typically originates from the floor of the vagina just in front of the cervix, that would be an ideal location for a pexy. However, there is a large artery in the area that makes doing a blind pexy too dangerous. The ideal cervicopexy procedure actually involves a flank approach as well as a vaginal approach. One surgeon inserts the needle vaginally, pushing it into the abdomen. The second surgeon, working through the flank incision, grabs the needle, passes it through the prepubic tendon and then back vaginally to the first surgeon.

The procedure is easier if the cow is off feed and if pneumovagina is created manually.

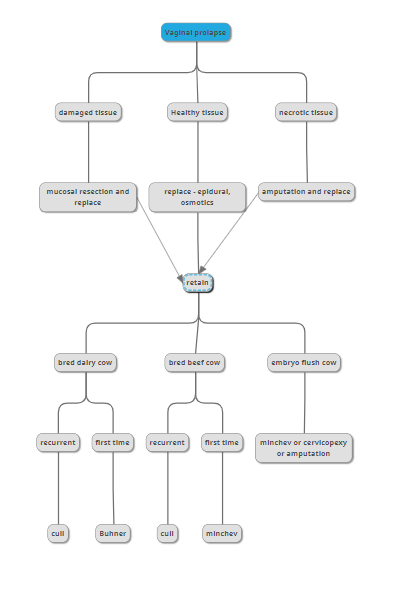

Malone’s decision tree – downloadable prolapse management

Resources

Prolapse section, Veterinary Care of Sheep and Goats textbook

Management of uterine and vaginal prolapse in the bovine, VCNA 2008 – pp 214-end. Note : While this article says vaginal prolapses can be either pre or postpartum, the majority are prepartum unless the cow is on hormones for superovulation. The chapter is more useful for uterine prolapses.

The purse string suture, Aneskey

cervicopexy notes from ACVS, 2016

Bovine Prolapse surgeries