Bladder, Urethra and Ureters

Ruminant urolithiasis

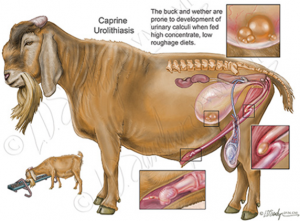

Urolithiasis is a common problem in goats and feedlot cattle. It is not uncommon in pigs, camelids and horses. The type, number and location of stones varies by species. Pigs and camelids can also develop urethral polyps which present in very similar manner to stones but are much harder to treat since we can’t readily remove them. Camelids tend to die due to related metabolic complications.

Horses present for hematuria. All the other species present for partial or complete urinary obstruction. Stones will often lodge in the vermiform appendage of goats and/or in the sigmoid flexure of all ruminants. Animals may be seen straining to urinate or defecate. Bladder or urethral rupture can occur within 12-24 hours if the obstruction is not relieved. Feedlot steers may be found dead, often with calculi on the preputial hairs. A vocalizing buck or wether should be assumed blocked by a urolith until proven otherwise.

Risk factors

Risk factors include high grain diets, early castration (probable risk), season (higher risk in fall/winter in the US) and decreased water intake.

Diagnostics

Passing a urinary catheter is generally not possible in ruminants or camelids due to the urethral diverticulum. Just because you can’t pass a urinary catheter does not mean the animal has stones. The most effective diagnostic test is a digital or manual rectal exam. In an obstructed animal, the urethra is often pulsing.

Imaging can be used to confirm or assess the number and location of stones. Most stones are radio-opaque. Ultrasound can be used to identify full bladders, urine leakage and occasionally urethral stones. The stifle is often right on top of the sigmoid flexure on radiographs so look carefully in that area.

. Caprine urolithiasis

. Caprine urolithiasisTreatment

Enable urination by amputation of the vermiform appendage, tube cystotomy or other procedure OR relieve the bladder via cystocentesis. The most common procedures are amputation of the vermiform appendage, penile amputation and tube cystotomy.

Amputation of the vermiform appendage

Amputation of the vermiform appendage can help temporarily. The offending stone is removed but there are often dozens of stones in the bladder and urethra. It is just a matter of hours before more come down the urethra and become lodged. This procedure may allow you to schedule the surgery in daylight hours rather than at 2am.

Perineal urethrostomy

Perineal urethrostomy is not a great choice in ruminants due to their propensity to stricture. It is acceptable in feedlot steers as their lifespan is limited. However, penile amputation is easier.

Penile amputation

Tube cystotomy

Tube cystotomy is recommended for most pet goats and any ruminant males used for breeding. Surgery is performed under general anesthesia. Cystotomy is performed, as many stones are removed as possible with gentle flushing and a tube placed in the bladder that exits the body wall. The tube allows urine to flow freely while the urethra is still obstructed. The remaining urethral stones will usually pass on their own after the urethra stops pulsating closed.

Antibiotic coverage (usually ampicillin) is maintained while the tube is in place due to the risk of ascending infection

The tube is removed once the goat can urinate on his own through the penis. The goats will usually start urinating normally once the urethra is cleared, even with the tube still in place. Generally we leave the tube in for at least 8 days to create an adhesion to the body wall (this number is pulled out of thin air, as far as I can tell)

Noteworthy

Tube cystotomy is also being performed in dogs with disk disease. The surgery is performed through a keyhole approach since the bladder does not need to be fully exteriorized for stone removal.

Tube cystostomy is effective for urinary outflow management in dogs with intervertebral disk extrusion. JAVMA 2023-12, Vol.261 (12), p.1-7

Modified tube cystotomy

Bladder marsupialization

Laser lithotripsy

Stone passage (removal, dissolution, relaxation)

Retrograde or anterograde flushing of the urethra tends to cause urethral rupture.

Saline flushes may help dissolve stones due to the pH of the saline. Saline can be flushed into the bladder via the tube cystotomy tube.

Minimize the risk of recurrence

Once a stone former, always a stone former. Dietary adjustments are needed:

-

- avoid alfalfa hay, oreo cookies, dog chow

- encourage dilute urine by salting the food. Owners can gradually increase salt levels to 3-5% of the dry matter intake or about 60-100 grams of salt for a 100kg animal

- ensure a reliable source of clean water

- soychlor or pasturechlor is the most effective dietary adjustment we have currently for herd level management

Many people incorrectly believe ammonium chloride in the feed is effective. It works but goats don’t like it. For effective use, it needs to be given orally as a medication. This means it works better in individual animal management rather than herd management. Table sugar helps mask the flavor. Ammonium chloride should also be given in a pulsatile fashion – it stops working if given continuously; titrate the dose to a level that acidifies the urine (pH <6.5) in the affected animal, then treat three days on, four days off. If owners can check urine pH, this may be a useful feed additive for phosphatic urolithiasis; check pH 5-7 hours after giving the acidifier. Oral D, L-Methionine at a dosage of 200 mg/kg can also decrease pH.

Measures to acidify urine may actually increase the risk of calcium carbonate stones – don’t overdo it!

Manage related complications and pain

Complications include uremia, urinary tract infections, ruptured bladders, and/or ruptured urethras.

Analgesics are needed, especially for goats. Goats are pretty sensitive to pain and will tend to be in rough shape for a day or two post-operatively. Consider phenazopyridine (relieves bladder irritation), narcotics and NSAIDs. Uremic animals are not edible. All uremia needs to resolve before an animal is shipped for meat. This can take several weeks.

Key Takeaways

- If you have an animal with renal compromise, be very cautious with NSAIDs, steroids, tetracyclines and aminoglycosides. Penicillins are generally pretty safe. Consider drugs excreted by liver if no other restrictions apply (eg fluoroquinolones).

- Goats get stones because of diet issues. Urethral pulsation = obstruction. Tube cystotomies rule. Do not flush the urethra – goat urethras easily rupture.

- Feedlot steers get stones due to diet issues. Penile amputation is recommended and the site will still stricture. Slaughter when no longer uremic. Uremic animals are not edible.

- Camelids die

- Pigs can have stones (removable) or polyps (not removable)

- DCAD (cation-anion) diets are most effective. Do not give soychlor to the breeding does as it also pulls calcium from the goat and leads to jelly babies (no calcium).

If clients use ammonium chloride (most goats won’t eat enough to help), they need to stop it intermittently or it stops working

Resources

Urinary calculi of small ruminants – VCNA, 2023 -MJ Cook; discussions options for prevention and control based on type of stones

urolithiasis anes and tube cystotomy_ Sheep and Goat Medicine- works through all the diagnostics and options for treatment in more detail

Modified tube cystostomy technique for management of obstructive urolithiasis in small ruminants, JAVMA | FEBRUARY 2024 | VOL 262 | NO. 2

General anesthesia for patients with renal or hepatic disease, DVM 360 2011 – SA perspective but nice review of what drugs are good or bad when your patient has other issues

1990 antibiotic associated complications with renal disease 1990 Reviews of Infectious Diseases- also for your files. hard to find this info.

Surgery of obstructive urolithiasis in ruminants, VCNA 2008 -good overview with nice references; good for your files

Summer 2005 newsletter case of the month (page 3-4)- I use this for soychlor dosing; for your files. Also totally agree with filling the foley balloon with saline vs air. They last longer

Effects of castration on penile and urethral development in Awassi lambs, 2007 Bulgarian J of Vet Med -finally some EBM on this topic

penile amputation -for those of you struggling to visualize or just wanting more: youtube video