LA umbilical disorders

Umbilical infections

Umbilical infections are most commonly seen in calves. Camelids and foals can also present with umbilical infections; these animals tend to be much sicker and present at a younger age.

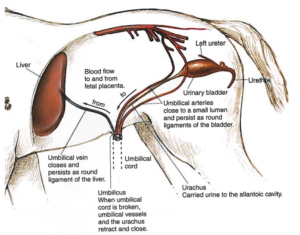

Normally the urachus dissolves and is not present at birth. The umbilical arteries (n=2) turn into the round ligaments of the bladder. The umbilical vein (n=1) becomes the falciform ligament (aka the round ligament of the liver).

Any of the umbilical structures can become infected. If infected, they tend to not dissolve normally. Urachal infections are the most common; umbilical vein infections the least common. It is common to have an umbilical hernia with an umbilical infection (see hernia section).

Diagnostics

Ultrasound can be used to identify gaps in the body wall, enlarged umbilical structures and the presence of infection. (see slide show above)

It is common to see both infection and hernia.

Treatment

Camelids and foals often get very sick if the umbilicus is infected. Management of umbilical infections typically involves either systemic broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy or surgical removal of the affected tissues (omphalectomy) or often times both. Medical therapy alone can be appropriate when infection is confined to the external urachal remnant and there are no signs of sepsis or infection elsewhere. However, exclusive medical management still carries a risk of serious complications, such as septic arthritis. Surgical intervention is recommended if sepsis is identified or if the foal’s condition worsens despite antimicrobial treatment.

Calves tend to have more chronic infections and are treated by removal or drainage of the infected structure. If possible, we remove the infected stalk without opening it or rupturing it. In calves, open hernia repair* is preferred over closed repair to evaluate for any signs of infected umbilical structures or adhesions that might be hiding in the abdomen. The infected stalk is identified and, ideally, removed. The infected component usually ends in a wider area that looks like a mushroom cap. This signifies the extent of the infection. Any vessel remnant proximal to that cap is usually solid and can be transected safely.

If the urachus is infected, it is best to remove the end of the bladder. Closing the bladder is easy, bladders stretch really well and this ensures all infection is removed.

Calves with umbilical vein infections often have liver involvement. This makes them higher anesthetic risks and poor doers. At surgery, the infected structure often requires “marsupialization” rather than removal. The infection often extends into the liver and this means it cannot be readily cut out at surgery. Instead, the infected vein is moved so it drains out of a smaller incision. A smaller incision is made away from the main incision. The umbilical vein is separated from the umbilical stump and moved to the new incision. At this site, the vessel wall is sutured to the skin edges to allow the infection to drain out. While this marsupialization has been done in foals, it is rarely indicated and has variable results. It can be challenging in calves due to the anesthetic risk of poorly metabolized drugs.

In real life, it is easy to “pop” these structures at surgery. If the umbilicus is draining and/or the infected structure is adhered to the body wall, drainage of most of the pus before surgery minimizes the risk of peritonitis. Once the drainage has mostly resolved, surgery can be performed to remove the tract and remaining infected structures. It is important to oversew or cover the drainage area at the time of surgery.

Calf hernias intro (consider this required viewing)- youtube link

*Open hernia repair- the hernial sac is opened for abdominal exploratory

Closed hernia repair – the hernial sac is inverted into the abdomen and is not opened.

Key Takeaways

- Urachal infections are the most common form of umbilical infection in calves. Surgery to remove the stalk includes amputating the end of the bladder.

- Close the bladder in 2 layers with inverting suture patterns that do not go into the lumen (eg Cushing). Avoid suture in the lumen of the bladder (nidus for stone formation). 3-0 monocryl works well in foals, goats and other smaller patients.

- Umbilical artery infections can usually be removed en bloc (cut after the mushroom cap and where the “artery” is thin). No blood flow to worry about.

- Umbilical vein infections -> liver and have a poor prognosis. Surgery involves marsupialization.

- Keep these animals on restricted exercise for 6-8 weeks to avoid recurrence of the hernia.

- No matter what you read, don’t do a vest over pants or a Mayo mattress suture for these. Appositional continuous pattern is best!

- Use suture material that will last the 6-8 weeks (PDS or Vicryl) and use large enough (#1, #2, #3) suture (depending on the size of the animal)

Resources

Umbilical masses in calves, ACVS- nice review; client focused

Calf umbilical surgery,-nice details if you will be doing these in the future – save for your files

We do recommend continuous patterns for all 3 layers of the body wall closure. I also agree with her suture removal time (14 days) but really keep calves and foals restricted for much longer than 14 days. What can happen if they bounce in the time frame between when the suture is no longer strong and body wall is still weak?

Comparison anesthesia techniques in calves undergoing umbilical surgery, Vet Anes Anal 2012 – for future reference

More visual details for those of you interested: youtube link

Umbilical abscess

Reuben and Katie’s Abridged Calf Umbilical Abscess w/captions

suture pattern in which tissue edges are turned inward