Equine Colic

The field colic – approach and management

The most common causes of after hours visits for horses are colic (35%), wounds (20%) and lameness (11%) (2020, A Bowden et al, Vet Record).

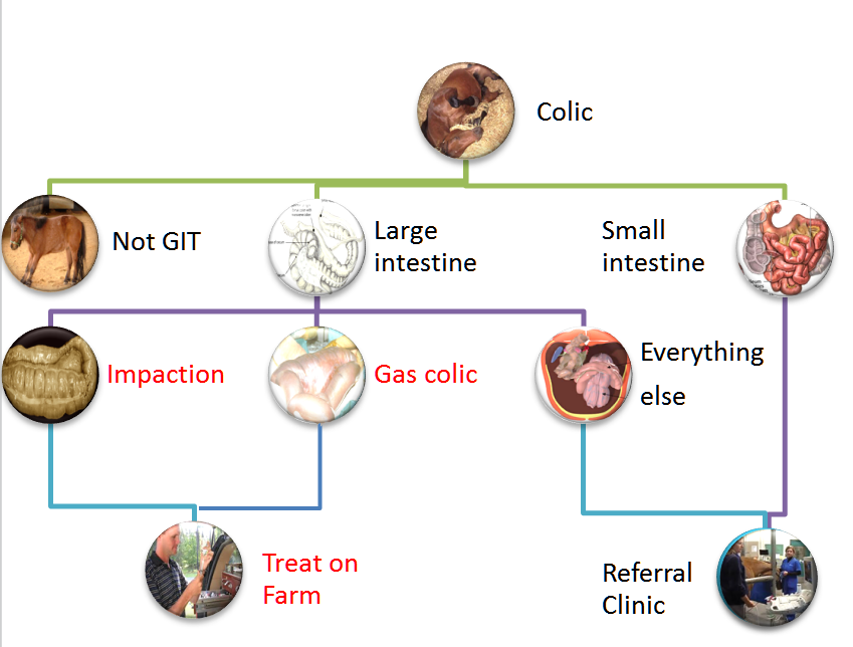

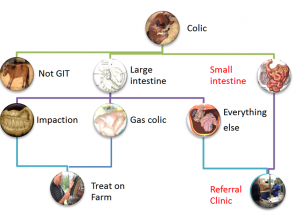

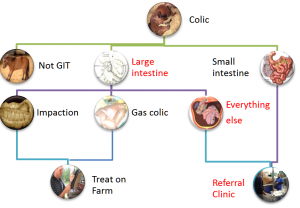

Two types of colic comprise 80% of the colics seen in the field. Gas (tympanic) colics and impaction colics are by far the most common and typically respond to one visit by the veterinarian. Luckily, treatment is similar enough that differentiating between them really isn’t necessary. If you can treat a gas colic, you can treat 80% of the colics you will encounter. This means the main challenge involves identifying and managing the other 20%. Almost all of the 20% “other” colics should be referred; it is reasonable to refer 100%* of the colics you see, including those gas and impaction colics.

In my mind, this is a bit like the car that stops running. I can add gas or try jump starting the engine. I check the gas gauge and try the jumper cables. If the car has gas and the battery has a charge, it is time to call an expert. For field colics, I can treat impactions and gas colics. I refer the rest to a hospital.

*A colic that walks off the trailer pooping and comfortable likely had a “curative” trailer ride. Bouncing might be helpful with getting that gas knocked loose (a LA version of burping?). Everyone is happy. The colic that isn’t better is the most stable it is going to be – ready for surgery or intensive medical management if needed. Waiting until it is obvious that things are bad significantly decreases prognosis!

Small intestinal colics

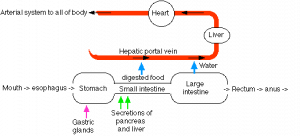

Horses with SI (small intestinal) lesions should be referred to a hospital that can provide 24 hour care, fluid set ups and surgical options. These horses typically need intensive care, surgery or both. Horses with SI lesions are sicker due to the large volume of secretions produced by the SI. With those secretions “lost”, horses will become dehydrated and will have electrolyte derangements.

Most horses with SI lesions are refluxing or will be soon. This means they need careful attention to avoid stomach rupture and cannot drink or eat.

Small intestinal disorders may need referral for surgery, reflux management, intensive therapy and/or just for maintenance of hydration. SI lesions are identified chiefly by the presence of reflux and/or identification of distended SI on ultrasound or rectal.

Hints that the horse has a small intestinal lesion:

- Reflux

- Due to small intestinal secretory activity, any type of small intestinal obstruction will eventually lead to reflux (fluid in the stomach). As horses cannot vomit, the fluid buildup will lead to a gastric rupture if not removed via nasogastric intubation. Large quantities of reflux will also cause electrolyte and acid base changes. Oral fluids will not go anywhere, so IV fluids are required to manage hydration.

- Small intestinal lesions can be differentiated from large intestinal lesions most readily if reflux is present. Only a couple of large intestinal lesions will lead to reflux (nephrosplenic entrapments and small colon impactions can reflux). Small intestinal lesions do not generally cause bloat. If bloat is present, it is likely a large intestinal problem.

- Low protein

- Small intestinal infiltration will lead to weight loss and low protein levels if it persists. Infiltrates in the villi increase the distance to the capillaries, making nutrient absorption less likely. Small intestinal inflammation can lead to loss of absorptive cells, also impairing nutrient absorption. When low protein leads to edema, it is definitely time for more intensive management. Steroids may be needed to control the inflammation and plasma may be needed to restore oncotic pressure.

- Metabolic derangements

- Stomach and biliary secretions are lost in the reflux, leading to more severe changes in electrolyte and acid-base levels in horses with small intestinal lesions.

Other LI colics

LI colics that need intensive care or are not responding to field treatment should be referred. This includes those that have a low protein (eg Lawsonia or right dorsal colitis), weight loss, fever or diarrhea. Hints that you are dealing with a different type of LI colic (vs gas or impaction) include more severe colic, abnormal rectal examinations, abnormal abdominal fluid or just lack of response to the normally effective treatment regimen. Many of these cases will need ongoing monitoring, more intensive treatment and/or surgery. Some displacements and sand colics can be managed in the field; most will benefit from hospitalization.

Cases that need surgery should be referred as early as possible. This may even mean referring in a case that is not yet surgical but isn’t following the normal course of response to therapy. Refer to the physiology/pathology section to learn how fast lesions become irreversible.

Indications for surgery include

- poorly manageable pain

- serosanguinous or abnormal abdominocentesis

- lack of response to therapy

- a need for further evaluation

Cases that need more intensive therapy:

- Reflux, diarrhea, or low protein levels necessitate iv fluids or colloids

- Horses with fevers may indicate contagious disease, particularly Salmonellosis and/or Clostridial infections

Not all clients will let you refer. Develop a mutual plan on when it will be time to stop.

Resources

Updates on Diagnosis and Management of Colic in the Field and Criteria for Referral, 2023 VCNA- good review of rectal palpation and criteria for referral

Management of colic in field, 2021 VCNA

Nasogastric intubation ibook(2015)- these are free downloads

Equine colic podcast- more of Malone

Review of Packed Cell Volume and Total Protein for Use in Equine Practice, 2001 AAEP

Evaluation of the colic in horses: decision for referral, 2014 VCNA

Current Topics in Medical Colic, 2023 VCNA

How to manage the challenging colic when referral is not an option, 2016 FAEP

nonspecific term meaning abdominal pain; typically applied to horses

blockage or partial blockage of the intestinal lumen by feedstuff