Equine tendons and ligaments

Tendonitis and desmitis

Pathophysiology content written by Dr. Vic Cox

Overview

Tendonitis (tendon inflammation) is a common debilitating injury seen in all types of performance horses. The tendons most often damaged in performance horses are the superficial digital flexor (SDFT) and the suspensory ligament (SL). Swelling of a SDFT with tendonitis results in a curvature of the flexor tendons in the cannon bone region. This swelling is referred to as a bowed tendon because the palmar surface of the tendon “bows” out. A ‘bowed tendon’ typically carries a guarded prognosis for return to a high level of athletic performance. The rate of recurrent injury is high.

Desmitis (ligamentous inflammation) is also relatively common. The coffin joint collateral ligaments are often damaged when hoof imbalance develops or with uneven ground. These injuries would be similar to an ankle sprain in a human. Due to the hoof wall, they may be undetected unless an MRI is performed. As with human ankle sprains, reinjury is common for several months. The suspensory body and/or branches can also become inflamed. This injury is most common in athletic horses. It often affects a single limb but can impact both forelimbs or a forelimb and a hindlimb. Soft ground can make the lameness worse.

Pathophysiology of tendonitis

There is controversy on whether degenerative changes weaken the tendon over time or whether tendon injuries occur as a result of a single overloading episode. Likely both occur and the cause may vary depending on the horse. Degeneration may be the result of anoxia (lack of oxygen). Low oxygen may be due to an inherent deficiency in the blood supply or due to vascular constriction caused by stretching during exercise. Others have found an increase in temperature in the core of the tendon. This rise in temperature may occur due to the inability of a deficient capillary system to remove generated heat efficiently. This hyperthermia, perhaps combined with mechanical stress, could cause cellular changes that result in depolymerization of the collagen. This heat could also destroy or interfere with the cross-linking which is required for optimum tendon strength.

Tendons have elastic properties and stretch to a certain degree with normal use. Stretching and rebound is a way of storing energy and then releasing it for propulsion. However, over stretching will cause damage. Transducers implanted on tendons of live horses indicate that the degree of elongation is 3% at the walk, 6-8% at the trot, and 12-16% at the gallop. Laboratory testing of isolated tendons indicates that they will rupture in the 12-16% elongation range. Therefore, the galloping horse is in the danger region but the duration of elongation during locomotion is less than a second.

Cyclical loading (stretching) and unloading of digital tendons results in recovery of about 90% of the energy that is put into the tendon to stretch it. As mentioned above, this is a process of storing and release of energy. The part of this energy that is lost (10%) is dissipated as heat in the tendon. When heat builds up in the tendon faster than it can be removed by radiation and blood circulation, this increase in heat can cause damage to the tendon. Therefore, heat, as well as mechanical strain can lead to tendon injury. During 7-10 minutes of galloping the core temperature of the SDFT can rise to 45-47 degrees C. This heat would kill fibroblast cells of the dermis. Tendon fibroblasts are but more heat tolerant, but, in some cases, their limit is exceeded. SDFT lesions often affect the core of the tendon more than the periphery suggesting that heat damage is a factor in the pathogenesis.

When tendon fibers are torn, capillary hemorrhage and inflammation result at the site of injury. Inflammatory products then result in further damage. Healing of tendon injuries requires stopping the inflammation and then restructuring the tendon with normal collagen (type I), with the fibers aligned along the long axis of the tendon and sufficiently cross-linked to provide strength. However, healing tends to occur by forming a knot of scar tissue: fibrous tissue (collagen type III) that is aligned in a variety of directions.

Over the first 8 weeks, the tissue is a fibrovascular mass of immature collagen fibers with little strength. During remodeling, these fibers are replaced with type I collagen bundles oriented along the lines of tension. Strength improves three-fold between weeks 8 and 12. By 24 weeks, the tendon scar is mature with longitudinally oriented fiber bundles. These bundles still contain some immature collagenous tissue; remodeling continues for many more months.

Chronic injury can lead to calcium deposits in the tendon as the body tries to strengthen the repair.

Hint : the number of letters = months of healing. Bone heals in ~ 4 months, tendons in ~ 6 months and ligaments in ~ 8-9 months.

Clinical signs

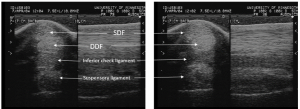

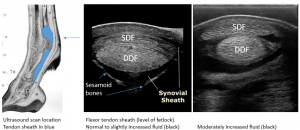

The most common site for tendon injury in Thoroughbreds is the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) in the mid-metacarpal region. This region has the smallest cross-sectional area and may be stressed to a greater extent at this level. The deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) is most often affected near the insertion of the distal check ligament or within the tendon sheath adjacent to or below the fetlock.

Initially, the cardinal signs of inflammation are observed both on physical exam and ultrasonographically.

The damaged tendon is warm, painful and often swollen. The horse is lame initially but this typically improves rapidly.

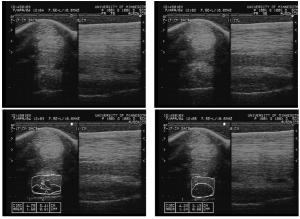

On ultrasound, tendon fibers are often disrupted and hemorrhage and/or edema is present (separating the fibers and creating enlargement of the tendon).

Desmitis is harder to detect on physical examination as the ligament is less likely to swell and the location makes any swelling harder to detect. The suspensory may be painful on palpation but many horses resent palpation of the suspensory body even without any underlying injury. Ultrasound and/or MRI are often needed to make a diagnosis.

Fluid in the tendon sheath is often seen with injury – it may be primary (the tendon sheath is damaged) or secondary (nearby inflammation causes tendon sheath inflammation – aka tenosynovitis).

Tenosynovitis generally has obvious effusion (fluid in the sheath). However, some areas are constricted by bands of ligaments (eg annular ligament); this pushes the fluid above and below the band.

Over time, the tendon stays swollen but the signs of inflammation resolve. The area may no longer be painful on palpation and the horse may be sound at a walk. However, the damaged tendon or ligament is weak and prone to re-injury.

Therapy

Medical treatment initially includes anti-inflammatory agents, cold therapy, physical support/compression (wraps or casts keep the swelling down and permit safe transport if needed) and complete rest until the initial inflammation resolves. Other agents may be given to increase blood supply to the area to speed healing (the rationale behind therapeutic ultrasound and the previous use of ‘firing’).

From R. Smith Treatment of tendinopathies -Equine Vet Educ. 2024;36:659–672.

The simplest and most cost-effective anti-inflammatory treatment is physical therapy consisting of the application of cold and/or compression [emphasis added] . Cold should be started as soon as possible and needs to be applied regularly (eg 20 min every 2–4 h).

Bandage casts can be applied to support the fetlock with a severely damaged tendon in the acute stage, often as a first aid procedure (Figure 5). Cast immobilisation has also been shown to reduce lesion enlargement in an experimental model (David et al., 2012).

Incorporation of topical anti-inflammatory agents such as DMSO under bandages (‘leg sweats’) have also been popular to accelerate the resolution of intratendinous inflammation although the efficiency of leg sweats at doing so has not been well established.

McCarthy and coworkers recently demonstrated the combination of compression and cold therapy was more effective at limb cooling than ice boots without compression (February 2025, Veterinary Surgery 54(3)).

For chronic lesions, controlled exercise is the key component of therapy. Controlled exercise is needed to stimulate healing and realignment of fibers along the lines of stress.

Exercise protocols are designed to stimulate fiber alignment without overuse and re-tearing. Controlled exercise is key. Horses are NOT turned out as this would immediately result in reinjury. Complete stall rest is contraindicated as this doesn’t provide enough force for proper fiber alignment. Once a horse is sound at a walk without NSAID administration, horses are allowed to walk in hand (under control) for increasing amounts of time. If ultrasound reevaluation shows improvement, trotting is started at low levels (2 minutes per day). Exercise is gradually increased as long as the horse stays sound. Ultrasound rechecks are essential to detect early damage. If the tendon shows signs of worsening on ultrasound (more damage), the training program is slowed and more time taken to move to the next level. Horses should still be on stall rest during this process. Turnout is not advised until the horse is cantering for ~10 minutes/day.

From R. Smith Treatment of tendinopathies -Equine Vet Educ. 2024;36:659–672.

The most important approach at this stage is early and progressive mobilisation, beginning with 5–10 min of in-hand walking exercise as soon as the signs of acute inflammation subside (signified by reduced swelling and lameness) and so long as there is no marked fetlock sinking/hyperextension. The duration of the daily walking exercise is gradually increased over a 3–4-month period before the introduction of trotting exercise

If healing is not progressing, other techniques may be used to minimize scar tissue and maximize collagen structure and alignment. Hyaluronic acid has been injected in the area in an attempt to prevent adhesions but has not been very effective. Polysulfonated glycosaminoglycan (PSGAGs) injections (IM) did help healing in experimental studies. Shockwave therapy is most likely useful at bone-tendon junctions and unlikely to be useful in the middle of a tendon (despite its widespread use). Various stem cells and stem-cell types have been injected in the region with varying results. The most promising include platelet rich plasma and stem cells of various sources; however, better controlled clinical studies are still needed.

Previously, surgical treatment has been considered only when horses do not respond to medical therapy and exercise or if they plateau (no further improvement). A recent retrospective study suggested that racehorses have a better chance of returning to the track with intralesional bone marrow injections and superficial check desmotomy than if just treated conservatively. Another option is “tendon splitting”. A scalpel is used to cut through the nonhealing region in order to increase blood supply to the area. It is most useful for core (central) lesions that aren’t healing with medical treatment.

If the tendon is swollen in the area of the fetlock, the palmar annular ligament may be cut to reduce pressure on the tendon. The area (damaged tendon + secondary tendon sheath effusion) can then swell without causing compartment syndrome effects. Finally, in one study, cutting the proximal check ligament aided in preventing recurrence of the tendonitis, not by increasing strength of the repair but by increasing the elasticity of the entire tendon unit. Cutting the proximal check releases the pull of the inflexible ligament on the SDFT leaving only the more flexible SDF muscle belly to “pull” on the tendon. In a more recent retrospective study, racehorses did better if the proximal check ligament was transected. However, the procedure can also lead to higher risk of suspensory ligament damage.

Shockwave therapy is often used in damaged ligaments that have plateaued and are no longer healing. Shockwave works best if there is a tissue interface (eg insertion of ligament on bone) at the injury. For suspensory ligament injuries in the hindlimb that won’t heal, neurectomy of the branch to the suspensory may be performed.

Bandage bow

A bandage bow is damage to the peritendinous structures leading to inflammation that looks like a bow. Luckily the tendon itself is not involved but you can’t tell that by appearance (they look similar). Ultrasound is typically needed to differentiate tendinous swelling (real tendonitis) from peritendinous swelling (bandage bows). Bandage bows often occur due to a bandage being too tight or too loose (sliding down and constricting). Bandage bows respond to anti-inflammatory treatment (cold therapy and NSAIDs). The horse should be stall rested until ultrasound can be performed to confirm the tendon is okay.

This sort of bandage on a horse is likely to cause damage at the edges -it can be pretty tight and put pressure on the soft tissue structures and tendons. Bandages should extend from the carpus to below the fetlock and NOT stop in the middle of the tendon.

This sort of bandage on a horse is likely to cause damage at the edges -it can be pretty tight and put pressure on the soft tissue structures and tendons. Bandages should extend from the carpus to below the fetlock and NOT stop in the middle of the tendon.

Key Takeaways

Tendonitis is inflammatory damage within a tendon. The superficial digital flexor tendon is most commonly affected and gives the appearance of a “bowed” tendon. Healing is slow and requires controlled exercise. Ultrasound is used to monitor healing as the initial signs of heat, pain, and lameness fade before the tendon is healed enough for regular work.

Treatment involves rest, cold therapy, compression and anti-inflammatory agents during the acute stage and stall rest+ controlled exercise after lameness resolves. Other therapies are added if needed due to poor healing.

Controlled exercise is essential. Tendon and ligament fibers require exercise force to align properly. Complete stall rest minimizes those forces resulting in a mishmash of fibers. Pasture turn out is too much exercise and leads to continued damage.

Bandage bows are not truly tendonitis but are swellings around the tendon due to improper bandaging. These heal readily.

Resources

Treatment of tendinopathies -Equine Vet Educ. 2024;36:659–672. lovely review and includes what to do as well as why and how.

Palmar/plantar tenosynovitis – client education, AEC- nice explanation with images

Ultrasonography of the equine pastern region – UGA free ibook

Equine shock wave therapy – where are we now? Equine Vet J. 2023;55:593–606. extensive literature review

Current use of biologic therapies for musculoskeletal disease: A survey of board-certified equine specialists. Veterinary Surgery. 2022;51:557–567. – doesn’t mean they work….

inflammation of a tendon sheath

An animal is put into the fenced in pasture and allowed to wander and exercise at will.