Equine tendons and ligaments

Tendon and ligament structure and function

Structure

Tendons must have high tensile strength and elasticity and be able to glide across other tissues.

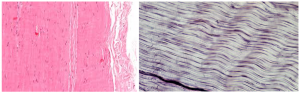

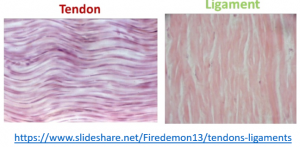

Tendons are comprised of an extracellular matrix of collagen, proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, and a few tenocytes. To create the high tensile strength, tendons are composed of type I collagen arranged in triple helix (tropocollagen) fibrils oriented parallel to the long axis of the tendon with a large amount of cross-linking. The cross-linking is possible due to the precise arrangement in healthy tendons. The tendons are arranged in bundles with an undulating pattern called crimp. This crimp structure permits stretching without tearing (elasticity).

Tendons are connected to muscle on one end and to bone on the other end. Fibrocartilage regions create zones of increasing stiffness at the tendon-bone junction.

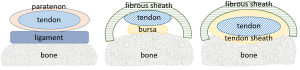

In areas where the tendon has to make a course change (eg over the fetlock joint), the tendon is usually surrounded by a tendon sheath. The tendon sheath is lined by synovium and forms a fluid filled cavity for the tendon. A bursa is similar to a tendon sheath except it only covers part of the tendon surface. Bursae are found between tendons and bony prominences (eg bicipital bursa). In other areas, the tendon is surrounded the paratenon, an elastic connective tissue sheath with an excellent vascular supply.

Tendons are relatively acellular. Tenocytes obtain nutrition from penetrating vessels (from tendon sheaths, paratenon, bony attachment) and the synovial fluid if within a tendon sheath.

Compared to tendons, ligaments stretch less and fibers are arranged in less of a parallel fashion and are not crimped. Ligaments may also contain skeletal muscle fibers. Ligaments are attached to bone on both ends or connect bone and tendons (so less stretch overall). Ligaments often function to bind bones together.

Tendonitis

Tendon inflammation is referred to as tendonitis; suspensory inflammation as desmitis. Injury occurs when the elastic forces of the tendon are overcome or the vascular supply is overstretched. Healing requires repair and realignment of fibers. Tendon healing requires approximately 6 months while ligamentous healing takes approximately 9 months.

Suspensory ligament degeneration

Degenerative suspensory ligament disease seems to be the result of excessive accumulation of proteoglycans that weaken the ligament. The disease is considered heritable and there is no known cure. The proteoglycan accumulation can affect tendons and other connective tissue structures, as well. As the ligament loses strength, the fetlock drops. Horses are typically very lame with abnormal hindlimb conformation (dropped fetlocks).

Key Takeaways

Tendons connect muscle to bone. Ligaments do not connect to muscle and tend to be involved with limiting rather than permitting stretch.

Both tendons and ligaments contain large amounts of type I collagen.

Tendons are often associated with a tendon sheath or bursa when crossing bendable bits.

Tendon fibers are crosslinked and aligned with weight bearing; when tendons are injured, they need weight bearing to know how to align.

Tendons require about 6 months to heal (under good conditions), while ligaments require 8-9 months.

Suspensory ligaments can also degenerate and weaken. The condition is considered heritable.