Female urogenital surgery

Teat trauma

Teats wounds are managed similarly to wounds in other species with the exception of milk flow.

As with other wounds, it is important to determine the level of healing potential.

- Is the wound acute or chronic?

- Is the wound clean or contaminated?

- Was the type of trauma blunt or sharp?

- How deep does the wound go? Any other structures involved?

- Does the wound have good blood supply?

- Is any skin missing?

- Are there any other factors that can interfere with healing?

- Has the wound been treated already? If so, with what? Response?

- Is the cost of treatment reasonable for the client?

Due to the good blood supply to the teat, superficial wounds heal well even with skin loss. Blood supply obviously comes from above so horizontal lacerations do disrupt the blood supply more than vertical lacerations. Blunt trauma can do internal damage that causes later issues; wounds created by a sharp object generally have a better prognosis.

Primary repair is ideal for full thickness wounds, so acute lacerations have a better prognosis than chronic wounds. However, partial thickness wounds do well regardless.

It is also important to consider the process of milking during the healing process. Machine milking is a vacuum process and is much less traumatic than hand milking. Machine milking can start as soon as fibrin seal forms across the suture line (approximately 6 hours in a healthy animal). Lactating dairy cattle have their teats cleaned 2-3x daily as part of the milking process; this also helps in wound healing.

Full thickness wounds

Wounds that extend into the teat lumen require special consideration.

Lactating animals

The repair of full thickness lacerations in lactating cows can be challenging. Adulteration of the milk with antibiotics and antiseptics must be avoided in lactating animals. Salves may help keep the wound moist and healthy but need to be food safe, as well.Teat bandaging is difficult and unnecessary.

Milk flow and milking will tend to keep the wound open. Fistula formation is more likely in lactating animals. With fistulas, the laceration heals but leaves an opening that permits milk to leak out the wound.

Wounds into the teat lumen significantly increase the risk of mastitis from environmental contaminants prior to repair so waiting to fix the laceration isn’t a better option. Lactating animals will also be losing milk as long as the wound remains open. This can be a significant financial loss. If it occurs, fistula formation also continues to increase the risk of bacterial contamination and mastitis.

Non-lactating animals

Full thickness wounds in non-lactating animals are a risk primarily due to the need for sedation and recumbency in these pregnant animals. Avoid dorsal recumbency and avoid xylazine sedation in the third trimester whenever possible.

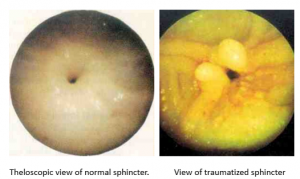

Sphincter wounds

At this time, we do not have any way to recreate the teat sphincter. The sphincter can be damaged by lacerations or blunt trauma. Cows with a laceration involving the sphincter should be treated by teat amputation, udder amputation or culling. Cows with blunt trauma to the teat end (eg from a foot) may rupture the sphincter. Parts will prolapse into the teat and interfere with milk flow due to a ball-valve type action. The prolapsed tissue can be trimmed but granulation tissue will form and block milking. This occurs within a few weeks. Prognosis is poor.