Equine joint disorders

Osteochondrosis

Pathophysiology

Osteochondrosis is due to abnormal endochondral ossification – the cartilage does not develop into bone as expected. Histologically, osteochondrosis is characterized by abnormal chondrocyte differentiation and formation of defective intracellular matrix. The process of ossification is interrupted due to loss of vascular supply and subsequent loss of chondrocyte nutrition. Abnormally thick cartilage develops. The abnormal cartilage is an area of focal weakness and can separate or collapse (fold inward). Repair is typically not possible due to the poor repair qualities of cartilage.

Two types of osteochondrosis develop: osteochondrosis dissecans (OCD) and osteochondral cyst-like lesions. The type of osteochondrosis that develops depends on the location of the abnormal cartilage.

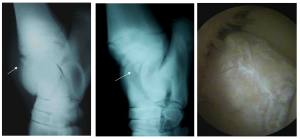

Osteochondrosis dissecans (OCD)

OCD develops when the abnormal cartilage occurs in non-weight bearing areas within the joint. Fragments of cartilage become partially or totally separated (“dissecting away”) from the parent bone. Some will stay cartilaginous and other fragments may ossify. The level of ossification will determine if they are visible radiographically.

Floating fragments cause mild inflammation and joint trauma. Horses do not typically show lameness in the early stages. However, the resultant synovitis (synovial inflammation) causes an increased production of synovial fluid and joint swelling. Over time, the joint capsule becomes more fibrotic and less flexible. Cartilage damage and arthritis can develop from the direct trauma and ongoing inflammation but it is a relatively slow process.

Common sites of OCD in the horse include the lateral trochlear ridge of the distal femur, cranial intermediate ridge of the distal tibia (DIRT lesions), lateral trochlea of the talus, and caudal aspect of the humeral head. DIRT lesions are the most common.

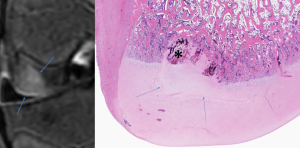

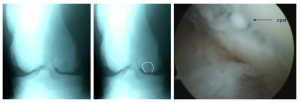

Subchondral cyst-like lesions

Subchondral bone cysts develop when the cartilage abnormality is in an area that is weight bearing. Instead of the overlying articular cartilage becoming detached from the subchondral bone, the cartilage becomes infolded (crushed by the weight). The crushed materials release inflammatory mediators into the joint, causing synovitis and joint swelling.

Affected horses are often lame and arthritis progresses more rapidly than with OCD. The amount of pain and inflammation are usually associated with the amount of weight-bearing articular cartilage involved. Cysts can “improve” over time, filling in with more normal bone. However, the articular cartilage on the surface does not usually gain normal strength.

The most common site of subchondral cyst-like lesions due to osteochondrosis is the medial femoral condyle (stifle).

Note: Cysts may also occur secondary to trauma to the cartilage, subchondral bone or both. Common sites for developmental cysts include the medial femoral condyle, glenoid fossa, and distal cannon bone.

Etiology

Several factors have been proposed as causative agents for osteochondrosis. These include genetic predisposition, rapid growth, nutritional mismanagement, and trauma. None of these factors can be identified as the most critical; most cases are likely multifactorial.

Osteochondrosis often affects rapidly growing animals; however, it appears to be more closely related to a high energy diet than to rapid growth. Controlled diet studies strongly implicate excess digestible energy (often excessive carbohydrates) as a factor in the development of osteochondrosis. Excess protein did not seem to make a difference. Diets high in calcium and phosphorus may induce osteochondrosis, as can abnormal copper (low) and zinc (high) levels. In another study, mares with wobbler syndrome (probably cervical OCD) were bred to similarly affected stallions. Offspring were not wobblers but had a high incidence of developmental orthopedic disease, including osteochondrosis. In Standardbreds, tarsocrural OCD has a heritability rate of 0.52 (high). Finally, trauma may precipitate disease when biomechanical forces act on structurally abnormal cartilage. This correlates with the identification of clinical signs in horses just starting training.

Older horses can develop osteochondral cysts and fragments due to wear and tear on joints and related changes in bone and cartilage structure.

Diagnosis

Osteochondrosis is most commonly diagnosed in young horses being put into work. This timing is more likely related to closer examination of the horse than to development of the disorder at this stage of life (ie it was probably there but not noticed). Joint effusion is the most common presenting complaint. Lameness may or may not be apparent but is more typically seen with cysts due to the weight bearing locations. Diagnosis is confirmed by radiographs. As this is a developmental disorder, both joints (eg both stifles or both hocks) should be radiographed as should any other joints that have effusion (particularly fetlocks). Radiographs may not show lesions in mild cases (not ossified, small cysts); ultrasound and/or arthroscopy may be needed to fully evaluate the joints.

Therapy

Nonsurgical treatment includes rest, controlled exercise, and minimizing joint inflammation. Nonsurgical treatment may be successful depending upon the site of the lesion and the intended use of the horse. As fragments can lead to osteoarthritis, surgical removal of any loose fragment is recommended. Cysts may be injected with steroids using ultrasonographic guidance.

Surgical treatment has become the treatment of choice for osteochondrosis and involves removing loose pieces of cartilage and debriding defective subchondral bone. Treatment of cysts involves decompression of the cyst (needles, curets etc). Injection with steroids or placement of screws (nonabsorbable and absorbable versions) across the cyst may improve the likelihood of future performance and shorten recovery periods. Prognosis is favorable for hock and stifle joints, depending upon the amount of cartilage damage at the time of surgery (up to 70-80% success rates). Prognosis is less favorable for shoulder, pastern, and fetlock joint lesions. These areas tend to develop progressive osteoarthritis.

Key Takeaways

Osteochondrosis is abnormal cartilage development (failure of endochondral ossification) leading to osteochondral fragments (joint mice) or cysts. Fragments occur in non-weight bearing areas but lead to local inflammation and joint changes. Cysts occur in weight bearing areas due to cartilage malformation or local trauma. The primary presenting complaint is often synovial effusion (fluid in the joint). Lameness is more likely to be associated with cysts; many horse with osteochondral fragments have joint effusion but are not lame. Lesions are frequently bilateral.

Resources

Large animal arthropathies, Merck. Updated 2022- good initial starting place

Environmental factors of equine osteochondrosis and fetlock osteochondral fragments: A scoping review – Part 1. The Veterinary Journal 308 (2024) 106249. One stop shop that explains how little we really know.

Equine subchondral lucencies: Knowledge from the medial femoral condyle. Veterinary Surgery. 2024;53:426–436. Review of pathophysiology and treatment

Just for fun

Osteochondral fragments from the

Distal

Intermediate

Ridge of the

Tibia