Equine podiatry

Laminitis

Definition

Laminitis is inflammation of the laminae that attach to the coffin bone and interdigitate with insensitive laminae of the hoof wall. Laminitis is a very painful condition that results in disruption of the laminar connections within the hoof. Laminitis = founder.

Pathophysiology

Many different things cause laminitis and they probably don’t all cause it the same way (ie have different pathophysiology). These causes can be separated into three main groups – endocrinopathic (metabolic syndrome, hyperadrenocorticism, grain overload), inflammatory (black walnut shaving exposure, endotoxemia) and mechanical (weight bearing due to contralateral limb lameness).

With inflammation, vascular leakage and secondary swelling occur within the hoof capsule. Basically, the laminae become swollen but swelling of the foot can’t really happen because of the hoof capsule. Instead, a type of compartment syndrome develops (swelling within a confined space). This swelling leads to pain, pressure necrosis and impaired blood flow. Other theories to explain laminitis include poor blood flow, vascular thrombosis, insulin/glucose regulation changes affecting cellular processes, basal epithelial cell stress and abnormal keratinization. Lately, adiponectin has been proposed to have a role, based on its regulation of cellular proliferation and protection against endothelial stress. Ponies are predisposed to laminitis; insulin dysregulation resulting in basal epithelial cell stress may be a key component.

In general, the toe region is the most damaged due to the limited vascular supply in that region.

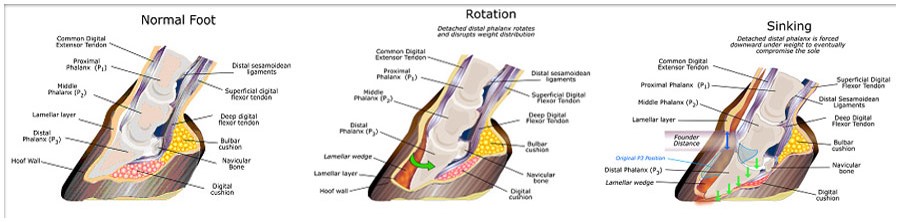

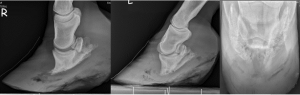

When damaged, the laminae stop holding the coffin bone up in the hoof. The weight of the horse and the pull of the deep flexor tendon battle it out to see if the coffin bone will rotate or sink. Rotation occurs when the laminar inflammation (and loss of use) is primarily dorsal. The deep flexor tendon pulls on the coffin bone and the tip dives toward the ground. The laminae can heal, but are now pulled abnormally. This creates funky hoof growth.

With more severe laminar damage or more weight on the hoof, sinking can occur. Basically the coffin bone is set free and it sinks toward the ground. This is bad.

As the coffin bone shifts downward from either rotation or sinking, a half moon shape or the tip of the bone may be visible on the bottom of the foot. This is not good. Survival is poor if the coffin bone is exposed. Saving these horses requires intensive prolonged hospitalization and is usually not successful.

Etiology

About anything can cause laminitis. Laminitis is common following release of endotoxin — GI colic /diarrhea /enteritis, metritis/retained placenta, etc. On the farm, you may see it following exposure to excessive grain intake, a change in diet (especially fresh pastures), black walnut shavings bedding, excessive weight-bearing due to contralateral limb lameness, hormonal changes (PPID- pituitary dysfunction, equine metabolic syndrome), coagulopathies, and steroid administration.

Laminitis can be readily induced by tubing horses with carbohydrates (grain overload model), iv infusion of insulin (hyperinsulinemia model of metabolic syndrome) and by using black walnut shavings for their bedding (topical absorption of toxins). Laminitis is a common complication of PPID in horses, presumed related to the high endogenous steroid levels. The famous racehorse, Barbaro, developed laminitis of his sound hind foot due to shifting weight off his fractured hind limb. This “secondary” laminitis led to euthanasia. We are seeing increased levels of laminitis related to insulin dysregulation in metabolic syndrome-affected horses. Adipose tissue releases inflammatory mediators that create even more issues.

Signalment

Laminitis is a disease of adult horses. Foals do not usually put enough weight on the foot to cause laminitis. It may be more common in older horses, particularly associated with PPID. Ponies are also more commonly affected by chronic laminitis, likely related to their propensity towards equine metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance.

Clinical signs

Acute laminitis

Signs include increased heat near coronary band, pounding digital pulses, sensitivity to hoof testers around the hoof wall, reluctance to stand on that foot (eg have the other foot picked up), increased heart rate and signs of pain. Horses develop a “sawhorse” stance due to bilateral forelimb involvement since they are trying to unload weight from the front limbs, especially the toe region. Horses may incessantly weight shift in the stall. Laminitis leads to a “walking on eggshells” gait.

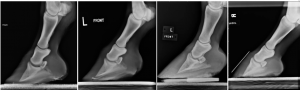

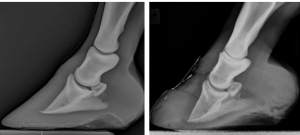

Chronic laminitis

These horses will often have a dished foot because the foot starts growing at a different angle due to rotation of the coffin bone, founder rings (rings around hoof wall), widening of the white line on the solar surface, changes in position of the coffin bone on radiographs, broken forward hoof-pastern axis, chronic pain, and chronic abscessation. Chronic laminitis may present as recurrent forelimb lameness.

Diagnostics

- Sensitive to hoof testers at the toe

- Should improve with palmar digital or basisesamoid nerve block

- Radiographic changes consistent with rotation, sinking or chronic laminitis (coffin bone remodeling)

- Classic gait (avoid toe pressure)

Radiographs

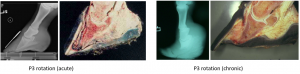

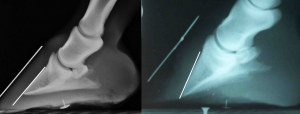

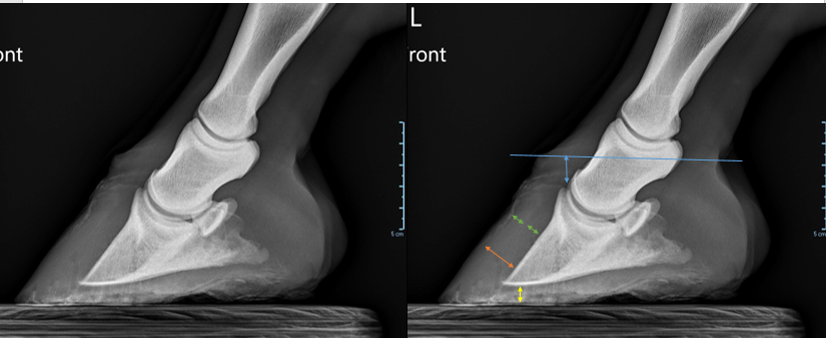

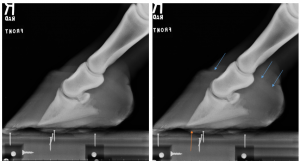

Rotation

- changes in angle between hoof wall and dorsal surface of the third phalanx

Sinking

Sinking may be missed on radiographs as it is more subtle.

- increased distance between dorsal hoof wall and dorsal surface of the third phalanx

- flattening of ledge at top of coronary band

- increased laminae width – In some radiographs you can see a darker line between the horny corium (hoof wall) and laminae. When the laminae is more than half of the total distance, that is also related to sinking of the pedal bone.

- limited distance between third phalanx and ground

- halo at coronary band (more prominent due to sinking of collateral cartilages along with coffin bone)

- gas around the third phalanx (infection)

Chronic laminitis

- remodeling of the hoof capsule (founder rings, dished shape)

- remodeling of P3 (“elf shoe”, deformity, lysis)

Treatment

Treatment is focused on the most likely pathophysiology. If swelling is a concern, we try to decrease swelling. If we are concerned about clotting, we try anti-clotting factors. Unfortunately, all of these type of laminitis look the same and we don’t yet know enough about what is happening inside the hoof. Therefore, horses tend to get a “shotgun” approach and we treat all possible forms.

Analgesia

All cases are going to require some form of analgesia. This often includes NSAIDs but many horses require additional pain relief or may be at risk of NSAID toxicity and need a change. Epidurals may help hindlimb laminitis ( but hindlimb laminitis is less common). Fentanyl patches, gabapentin, iv infusions of narcotics or ketamine, and acupuncture have been used with some success.

Remove the inciting cause

Remove the inciting cause (retained placenta, black walnut shavings, etc). If the horse ingested too much grain or other toxins, mineral oil or activated charcoal may be administered via nasogastric tube to minimize absorption and speed transit. Metabolic syndrome should be addressed by weight loss and any indicated medications or feeding changes. PPID (Cushings) disease should be treated.

Limit walking

Walking requires laminae to work hard to keep the pedal bone in position. If the laminae are dysfunctional or damaged, walking will only cause more damage. The horses should not be walked more than is absolutely necessary during acute or inflamed stages. There is recent evidence (see AJVR 2025 article below) that weight bearing without ambulation also causes damage; however, we don’t yet know if this research will apply to clinical cases or if standing still is the better of two evils.

Decrease swelling/impact of swelling

Swelling inside the hoof capsule leads to more damage. Horses may be given DMSO or other agents to decrease swelling. Ice therapy may also help with swelling. The hoof capsule can also be rasped to allow a bit more swelling by creating a thinner, more expandable wall. Currently we have moved away from more drastic hoof capsule removal. We used to remove the entire dorsal hoof capsule to allow swelling but it creates lots of challenges with normal hoof function and healing.

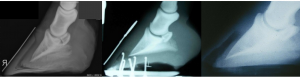

Support the coffin bone

Gravity is pushing the bone downward and the deep flexor tendon is pulling it around. We can relax the pull of the deep flexor tendon by elevating the heel in cases with rotation (this does not help cases of sinking). For sinkers, counteracting gravity is challenging. In acute cases, builders styrofoam can be used to make a soft support that molds to the horses foot and distributes weight.

Sand or peat moss can work similarly. “Lily pads” are rubber pads designed to support the frog and provide a small amount of heel elevation. In severe cases without financial restrictions, horses can be placed in a sling to minimize weight bearing.

In more chronic cases, the foot is trimmed or shod to enable easy turning or “breakover“*. Heart bar shoes are designed to use the frog and heel for more weight bearing, removing some of the stress from the laminae. Shoes may also be applied backward to put more support in the heel and avoid pressure at the toe region. The EDSS (Equine digital support system shoe) is designed to flex based on the horse’s response. Farrier recommendations vary significantly over time!

Nailing a shoe on the foot is avoided in acute episodes as this is too traumatic and painful. Glue on shoes or foot boots can be used to hold pads in place during the acute stages.

*breakover is the time from when the horse starts to take a step until the toe leaves the ground. A long toe leads to a longer breakover time.

Encourage blood flow

Due to sluggish blood flow and constricted capillaries, clotting is involved in many forms of laminitis. Low dose heparin, aspirin (every other day) and other platelet mediators have been tried and are often used.

Acepromazine is used with the goal of vasodilation.

Even though walking would encourage blood flow, it is contraindicated in laminitis due to the related damage.

Surgery

Surgery is considered in more chronic cases with significant rotation of P3. The goal is to realign the rotated coffin bone so that the pull on the laminae is more normalized. Cutting the inferior check ligament may be sufficient in a few cases. In many cases, the deep flexor tendon is transected in the pastern region or in the mid-cannon bone region. This temporarily relieves the pull on the coffin bone. The surgery must be accompanied by appropriate farrier work to ensure the tendon heals with the desired conformation. If the heel is left long, the tendon will heal back in its original position. By lowering the heel at the time of surgery, we hope to encourage healing in the more desirable position.

Minimize further trauma

Chronic laminitis cases are prone to hoof abscesses. Abscesses cause inflammation (inflammation = inflamed laminae= laminitis) and add to the damage. Any acute exacerbations of pain should be evaluated to determine if it is recurrent laminitis (often bilateral) or a hoof abscess (often unilateral). Of course that inflammation tends to set off the laminitis in both feet (one is direct since inflammation of the laminae involved, the other foot indirectly due to increased weight bearing).

Other inciting factors should also be avoided (lush pastures, hard surfaces, grain overload) as these horses are at increased risk of recurrent laminitis.

Prevention

Retained placenta, colitis, endotoxemia, excessive weight bearing due to a contralateral limb lameness, and excessive grain intake can all cause laminitis. Other treatable risk factors include PPID (Cushings) and obesity.

Because the amount of damage present by the time clinical signs are noticed, treatment is very difficult. Our focus needs to be on prevention. If the horse is at risk, we try to prevent damage:

- Ice the lower limb to decrease metabolic requirements

- this is easier said than done as it needs to be continuous.

- currently it is easiest to use a fluid bag filled with crushed ice and water; no dry cold therapies have been shown as effective

- Support the foot and limb via deep sand or peat moss bedding and/or styrofoam pads

- Administer mineral oil/charcoal through nasogastric tube to bind ingested toxins, minimize toxin absorption and encourage faster movement of any grain or other substances through the GI tract

- Pentoxifylline or polymyxin B are administered to bind endotoxin and prevent endotoxic action

- Flunixin meglumine can be given for both its anti-inflammatory and antiendotoxin properties

- Bismuth subsalicylate and/or kaolin are given to bind endotoxin in cases of colitis

- Lower insulin levels if indicated; however, we do not have an effective drug for this at the current time. Ertugliflozin has shown some promise in Australian studies.

Prognosis

Prognosis is based on clinical signs, rate of change in the foot, and amount of sinking (+/- amount of rotation if severe). Sinking is bad.

The prognosis is poor if you can’t pick up the other foot, the horse needs continued large amounts of analgesics, the coffin bone is sinking or is exposed at the sole, or if you can’t get rid of the inciting cause.

Sequelae

Pain, rotation of the third phalanx, sinking of the third phalanx, chronic abnormal hoof growth (rings, dished foot), chronic infection (hoof abscesses) due to damage to white line, and recurrent episodes of laminitis are all potential sequelae to a bout of laminitis.

Since horses are prone to recurrent laminitis, it is crucial to take radiographs early on in the diagnosis. The rate and severity of changes can help determining severity but you need to know the starting point.

Key Takeaways

Laminitis is bad

- Clinical signs include shifting weight, lying down, hoof tester sensitivity, and “walking on eggshells”

- The coffin bone can rotate or sink. Sinking is worse.

- Ice can help minimize laminitis develop in high risk cases

- Keep swelling minimal (NSAIDs) and avoid exercise.

- Horses are prone to new bouts of laminitis and to abscesses

- Treatment is supportive and surgery can be used to realign the hoof-pastern axis

Resources

A review of cellular and molecular mechanisms in endocrinopathic, sepsis-related and supporting limb equine laminitis. Equine Vet J. 2023;55:350–375.- lots of pathophysiology

A review of laminitis in the donkey. Equine vet. Educ. (2022) 34 (10) 553-560. Nice overview for horses too!

Pharmacology of the equine foot: Medical Pain Management for Laminitis. Vet Clin Equine 37 (2021) 549–561- good reference to have on file

“Feeding the Foot” Nutritional Influences on Equine Hoof Health, Vet Clin Equine 37 (2021) 669–684- nice review of risk factors, pathophysiology and therapies

Cryotherapy Techniques. Vet Clin Equine 37 (2021) 685–693

Clinical insights: Treatment of laminitis, EVJ 2019

Radiographic and radiological assessment of laminitis, EVE 2013 – excellent resource for measurements

Used in horses to describe the end of the stance phase: the period of time from when the heel is off the ground to the time when the toe is off the ground. This time window is prolonged with long toes and when a horse is shod. A longer breakover requires more joint motion.