Equine Lameness

Interpreting the lameness examination

Horses do not make it easy. A very lame horse may avoid weight bearing on a limb while at rest or point the sore limb forward but horses need to use all four limbs to move. Horses cannot carry (hold up) a limb like a dog or cat can.

Horses can also have more than one lame limb. However, one limb is typically the most lame and that difference can be identified. We use techniques such as footing changes, lunging and flexion tests to exacerbate the difference.

Newer diagnostics such as standing CT typically find multiple lesions; however, this does not mean the lesions are causing the lameness.

As a novice, try to determine if 1) the horse is lame and 2) if it is a forelimb or hindlimb lameness. You can move on from there with practice.

When a limb is painful, the horse will try to adjust its weight to avoid much pressure on the limb. Changes include:

- using the head to shift weight off the lame leg

- changing how long the horse bears weight on the lame leg

- minimizing how much the joints on the lame leg bend

Lameness evaluation is not a sensitive test, even in the hands (eyes) of experienced practitioners. Our ability to detect change is low and horses adapt to a pain in multiple ways. Often more than one limb is painful. These factors commonly lead to inaccuracy. The active lameness exam is a starting point. If you don’t find anything of importance, check again to see if you could be missing the painful limb(s) or are potentially looking for pain that doesn’t exist.

Forelimb lameness

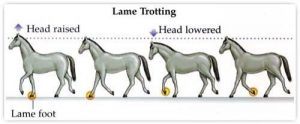

The classic sign associated with forelimb lameness is a “head nod“. The horse uses the “head nod” to shift the weight of its head in order to change the weight on the sore limb. The head is thrown up in the air when the lame leg is weight bearing. Since the head is pretty heavy, this moves the center of mass toward the hindquarters, putting less weight on the lame forelimb. As a secondary result, the head falls back toward the ground when the sound leg is weight bearing. We say “down on sound” rather than “up on lame” but either works. We can often hear a louder landing on the sounder limb, as well.

The horse may quickly shift off the lame leg due to the pain in weight bearing. This rapid recovery or shifting to the good leg results in an asymmetrical appearance to the gait but is harder to detect.

Sore joints are also held more stiffly. This can result in toe dragging. Toe dragging can be heard when the horse is moving on solid ground and/or seen because of sand or footing being thrown into the air as the foot drags. You may also notice that the fetlock on the sound limb sinks more because of greater weight being put onto that limb.

Forelimb lameness is more challenging when the problem is bilateral, such as with navicular syndrome. The horse can’t decide which leg to bear more weight on and instead shows a short choppy gait.

Horses with forelimb lameness will often be sore in the shoulder region even if foot pain was the original issue; this is due to abnormal carriage of the limb. Always check the foot for sensitivity even if the shoulder seems sore on palpation.

In the forelimb, the source of the majority of the lameness is in the foot.

Hindlimb lameness

For the hindlimb, we look at hip excursion rather than head nod. The more lame limb moves up and down more. This can be seen at the level of the tuber coxae or ischial tuberosity. Normally the hindlimb joints bend and the hip doesn’t move up and down much. However, if the joint(s) hurts, the horse will try to avoid bending it. To lift the foot, the horse has to lift the whole leg (raising the hip more). A greater hip excursion (more total vertical movement) is usually found on the lame limb. You will hear about hip hikes and hip drops; it is more useful to concentrate on total movement. Caveat: this is oversimplified. There are many ways to look at hindlimb lameness and more than one may be needed to determine which leg is lame. The most robust is the difference in tuber coxae movement between the hindlimbs.

We can also use toe dragging, decreased flexion and rapid recovery in the hindlimb.

Horses with hindlimb pain will often have sore or stiff backs due to changes in how they use their backs to propel themselves forward.

In the hindlimb, the hock is the source of the most causes of lameness.

Rule of sides

Occasionally a horse will throw its head forward with a hindlimb lameness (hindlimb head nod). This means when the lame hindlimb hits the ground, the horse has a head nod down on the contralateral forelimb. Due to how the trot works, this can look like a forelimb lameness on the same side.

Example; The horse is lame on the left hindlimb. If it throws its weight forwards, the head will nod down on the right front limb. We would typically interpret a right front nod as a left front lameness. Therefore, a left hindlimb lameness may be misinterpreted as a left forelimb lameness.

Since head nods are harder to interpret a walk, the rule of sides is typically used when head nods are identified at the trot.

A recent study showed that the withers can also help differentiate between fore and hind limb head nods if the observer is using a device to measure asymmetry in the withers. At least 80% of horses with a forelimb lameness have asymmetrical withers movement. This movement matches the head nod, pointing to the same lame forelimb. If the nod is from a hindlimb lameness, the withers do not match and point to the opposite forelimb as compared to the head nod (head nod says right fore, withers analysis says left fore; this means right hind).

Lameness grades (AAEP)

- Grade 5: non-weight bearing

- Grade 4: lame at a walk

- Grade 3: lame at a trot

- Grade 2: lame consistently under special circumstances (eg lunging)

- Grade 1: lameness difficult to observe and inconsistent, regardless of circumstances

We try to exacerbate the lameness using flexion tests, lunging, different footing and wedge tests. Flexion tests make joint pain more evident; it does not make bone or tendon pain worse. Lunging makes the inside limb bear more weight and makes any weight bearing pain more obvious. Hard ground also worsens bone and weight bearing pain. If the pain is in the tendons/ligaments, the outside limb will be more painful during lunging and the lameness will be worse with soft footing.

Key Takeaways

Oversimplified

- horses with a forelimb lameness will have a head nod with the nod down on the sound limb

- horses with a hindlimb lameness will have a disparity in the movement of the tuber coxae, with more movement on the lame limb

- horses with an apparent left forelimb lameness may actually have a left hindlimb lameness; ditto for the right

Resources

Lameness Evaluation of the Athletic Horse, Vet Clin Equine 34 (2018) 181–191- thorough review