LA Orthopedic Emergencies

Lacerations involving synovial structures

A soft tissue laceration that is located over or near a synovial structure (joint, bursa, tendon sheath) may extend into the synovial structure with the initial injury and/or during the evaluation and treatment process. These lacerations are considered emergencies and should be examined and treated as quickly as possible. While these can happen in any species, horses are prone due to the limited soft tissue covering of the limbs and their propensity to kick things that worry them.

Systemic evaluation

- Perform a brief physical exam (heart rate, respiratory rate, mucous membranes, etc.) to assess the systemic health of the animal. Think about why the animal could have gotten the laceration in the first place. There could be an underlying issue, such as colic, that should be identified.

- If the animal is shocky (high heart rate, prolonged CRT), neurological or colicky, consider early referral. Hemorrhage control should be attempted prior to referral.

- If the injury is acute, the animal may or may not be lame. There is no way of determining whether or not there is synovial structure involvement just based on degree of lameness.If the injury has occurred a few days prior to examination, the animal may become suddenly non-weight bearing lame. This is generally because inflammation starts accumulating in the joint, thus increasing the pressure and pain. If the infected area is draining, the animal may not be lame even with joint involvement.

Laceration evaluation

- The animal will likely need to be sedated. Avoid acepromazine if there is a risk of moderate to severe blood loss.

- Local nerve blocks are useful to improve the examination quality and to increase the duration of the sedation.

- Clip the area around the wound. This will make the area cleaner and much easier to work with. You can place sterile lube in the wound and around the edges to prevent excessive hair and debris from entering the wound.

- Synovial fluid could possibly be seen coming from the wound, but this is not always the case. This is more likely in an acute wound, rather than a chronic one

- Aseptically clean around the laceration. Never clean with chlorhexidine scrub or solution when there is potential for synovial involvement because it is toxic to joints. Sterile saline is an excellent option for these situations (as well as other sensitive areas like around the eyes). Dilute iodine solution can also be used to clean the site, but remember that iodine is inactivated by debris in the wound.

- Lavage the wound with sterile saline or LRS. “The solution to pollution is dilution”

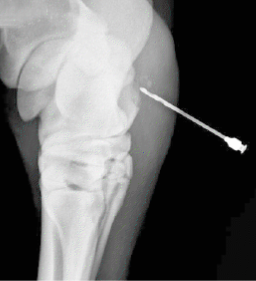

- Using a sterile glove +/- sterile probes or other surgical instruments, perform an examination of the wound. Try to determine the margins of the wound, how close it is to synovial structures, and the depth of the wound. The sterile probe can even be used when taking radiographs to get a better idea of depth and direction of the wound.

- Administer a tetanus toxoid if the animal has an unknown tetanus vaccination history or if the horse/small ruminant has not been vaccinated for tetanus in the last 6 months.

- **Always offer referral when there is a wound with potential synovial structure involvement**

Joint integrity assessment

It can be very difficult to tell if joint fluid is leaking from a joint. The following are options.

Joint pressurization

The most efficient means of evaluating joint (or other synovial space) integrity is to attempt to pressurize the joint. Identify a “normal” (covered in skin, not lacerated) area and prep the site for a joint injection. Inject sterile saline or LRS into the joint. Eventually the joint should pressurize and become harder to inject. Joint fluid may spurt out of the needle when the syringe is removed. This means the joint is currently intact. If no pressure develops despite copious fluid injection (relative to the joint size), it is leaking out and the synovial space has been opened.

If it appears closed, flex and extend the joint following the distension to fully assess.

Radiographs

Radiographs are not the most sensitive way to assess for joint involvement: however, they are quick and easy to do in the field. Look for gas near or in the joint space. This indicates a path for room air to enter the joint space. Radiographs can also help assess for any bone involvement or fractures that may have occurred during the trauma.

You can also inject sterile contrast media into the joint of concern (at a site distant from the wound) and then take radiographs. **This is one reason why it is important to be aware of and comfortable with different sites to inject each joint. Injecting into a path within the wound is not likely to force contrast material into the joint.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is another quick and non-invasive way to assess a wound and can also be done in the field. Place a sterile glove or sterile rectal sleeve on the ultrasound probe, which will enable you to use the ultrasound directly in the wound without contaminating the wound or your ultrasound probe. Ultrasound can be used to assess the depth and direction of the wound.

Some indications of joint involvement include: increased synovial fluid within the joint, gas or fibrin present in the joint, and/or a thickened synovial membrane.

Note: too much air in the wound will make ultrasound difficult.

Arthrocentesis

Clip and aseptically scrub a site on the joint that is distant from the wound. Insert a needle into the prepared area and always start by taking a sample for culture and cytology. This fluid can be analyzed for evidence of joint contamination immediately after retrieval, either microscopically or grossly (especially in the case of chronic joint infection).

**Never perform arthrocentesis on a joint through the wound or through cellulitis. This will drag bacteria into the joint.**

Follow up care

- Even if no joint involvement is suspected, after distending the joint or examining the cytology sample, antibiotics may be injected directly into the joint as prophylaxis.

- If there is joint involvement:

- Start the animal on systemic antibiotics as quickly as possible or perform a regional limb perfusion, depending on where the wound is located and the species involved (horse).

- Thoroughly lavage the joint using standing sedation or general anesthesia, depending on the case. This can be done by inserting a large gauge (14 g) needle into a site distant from the wound. This will likely be the same location that was prepared for the diagnostic arthrocentesis. Lavage with at least 1-2 L of sterile LRS. Do not forget local anesthesia!

- Following lavage, administer intra-articular antibiotics.

- If the wound and joint are severely contaminated (usually chronic wounds), do not suture the wound closed. This allows for maximum drainage and enables you to lavage the wound and joint thoroughly every day until there is no sign of infection cytologically or from culture results.

- If the wound is acute and not severely contaminated, the wound can be sutured closed, but leave a small opening to allow for fluid drainage.

- Regardless if the wound is sutured closed or not, apply a topical antimicrobial agent and a sterile bandage

Key Takeaways

Assume the joint is infected until proven otherwise. Remember, cattle can get infected joints without a wound (hematogenous spread).

Submit any samples for culture and sensitivity

Start systemic antibiotics

Refer for joint lavage

References

Crosby et al (2023) Current treatment and prevention of orthopaedic infections in the horse. Equine Vet Educ. 2023;35:437–448. Excellent review. Download if planning on an internship or residency.

Biasutti A et al (2021) A review of regional limb perfusion for distal limb infections in the horse. Equine vet. Educ. 33 (5) 263-277

Orsini, J. A., & Divers, T. J. (2014). Equine Emergencies: Treatment and Procedures. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders.

Murray, S. J. (2012). How to Manage Penetrating Injuries of Synovial Structures in the Field. AAEP Proceedings, 58, 221–227.

Moyer, W., Schumacher, J., & Schumacher, J. (2011). Equine Joint Injection and Regional Anesthesia. Chadds Ford, PA: Academic Veterinary Solutions, LLC – highly recommended resource