Large animal masses

Abscesses related to systemic infections

It is important to identify systemic infections. These tend to 1) be infectious to other animals and 2) be harder to treat due to recurrence of lesions.

Caseous lymphadenitis

Sheep and goats with abscesses may be infected with Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis and have caseous lymphadenitis (CLA). Sheep tend to develop onion like abscesses (firm, layered pus) and are prone to internal abscesses, while goats get white creamy pus filled lesions and are more likely to have external abscesses. The abscesses are generally infected lymph nodes; the submandibular nodes are a common site.

This organism is very infectious and very hardy. Lancing abscesses will lead to more environmental contamination. Removing abscesses surgically can become expensive due to the frequent incidence of new infections in the herd (same patient and other patients). Tulathromycin injected into the lesion or subcutaneously into the goat helped resolve lesions in one study. At the UMN, we did not find it that effective. Generally, to control this disease, all infected animals must be culled and no new animals placed in the space for at least 8 months. This is often unpalatable to owners. Additionally, animals with more than one abscess or those with a draining abscess are usually rejected at the slaughterhouse. Vaccination may be helpful in sheep.

*Culturing small ruminant abscesses is important and client education is a crucial part of therapy.*

Pigeon fever

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis (equine serovar) is a growing problem in horses and leads to superficial and internal abscesses. This disease has been localized to California and other western states in the past but is expanding as the vectors involved in its transmission enjoy global warming (likely horn flies, stable flies and house flies). The most common presentation is abscesses in the pectoral or ventral abdominal area, leading to the name “pigeon fever” as they look like they have big pigeon-like breasts.

It can also lead to ulcerative lymphangitis on the limbs of affected horses. Horses in endemic regions may have some resistance to the organism; as it enters new territory, it may be more virulent. Most cases are seen in the late summer and fall but it has been identified year round and the seasonality may be shifting to midsummer months. This version of the organism is also very hardy in the environment and can survive at least 2 months on fomites and in the soil for 8 months. Affected animals should be isolated. Corynebacterium sp can infect people but is generally not infectious unless individuals are immunocompromised.

Strangles

Horses with abscessed lymph nodes may also have strangles (Streptococcus equi). The lymph nodes in the head are most commonly affected but the infection can affect any lymph node.

If the horse has nasal discharge or if there is a history of strangles in the barn or the community, strangles should be at the top of your differential list and appropriate precautions taken to limit its spread. You and your vehicle can be fomites! Streptococcus equi can survive in the environment and on your gear for up to 4 weeks.

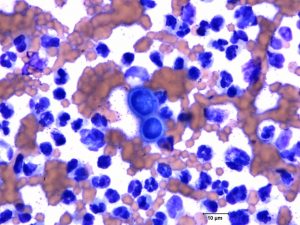

Blastomycoses and other infections

Other bacterial and fungal organisms can also create abscesses or masses in all species. Most of these are easily spread between animals of the same species and many have the ability to cross species lines (including humans). We have seen blastomycoses infections in horses in this area. Cytology and culture can help figure out what you are dealing with. Chronic abscesses may need a specialist.

Osteomyelitis blastomycoses in a Minnesota horse

Key Takeaways

Keep in mind those organisms that are serious environmental contaminants such as

- Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis

- Streptococcus equi

- Blastomycoses

Resources

Can vaccinating sheep reduce the occurrence of caseous lymphadenitis? Veterinary Evidence, 2020 : Vol 5, Issue 1. [Article will download]

AAEP infectious disease guidelines: pigeon fever, revised 2023

Diagnosis of caseous lymphadenitis in sheep and goat, Small Ruminant Research, January 2015, Vol.123(1), pp.160-166

Control of caseous lymphadenitis, VCNA Vol.27(1), pp.193-202, 2011

Comparison of three treatment regimens for sheep and goats with caseous lymphadenitis, JAVMA Vol.234(9), pp.1162-6, 2009

Eliminating Chronic Disease Using a Farm-based Approach – Maine study, 2014

inflammation of the lymphatics, associated with swollen limbs and skin ulcerations