Large animal masses

Abscesses

Abscesses should show signs of inflammation: heat, pain, swelling, redness, and/or loss of use. Abscesses can result from trauma (puncture wounds, lacerations, surgery); can develop from necrotic tumor centers, bone sequestra or foreign bodies; or can be related to systemic infections. Wounds need to close from the inside out. If the opening of the wound closes too soon, it will trap the infection inside. Similarly, contaminated or infected wounds are rarely closed or at least not closed completely so that the infection can drain.

Abscess management podcast – overview (10min)- note that I said tap water is better than isotonic solutions; I meant to say hypo/hypertonic – these are less safe than tap water.

View the transcript for the Abscess management podcast

Ventral drainage

The primary principle of abscess management is ventral drainage. If the abscess isn’t opened or if the opening is above the floor of the abscess, the abscess will generally continue to exist.

Abscesses with Friends – Dr. Will Powell w/captions

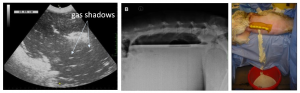

Ultrasound can be very useful to identify the extent and ventral aspect of an abscess. Ultrasound also shows blood flow (which is often increased) and allows the surgeon to avoid large vessels. Abscesses usually show a mixed echogenicity and a capsule is often visible. Ultrasound can also be used to identify the depth of the abscess and permit more accurate needle selection and incision depth.

Gas in the abscess indicates either an opening to the environment or an anaerobic infection. Ultrasound is also useful for identifying foreign bodies or bone sequestra that are preventing healing in chronic abscesses or wounds. However, ultrasound isn’t useful when there is gas in the wound; do your ultrasound before making holes to enable better evaluation of the structures.

Radiographs are useful for gas detection; fluid appears as a soft tissue density and may not be readily differentiated from soft tissue structures; gas will usually highlight the abscess but isn’t always present.

Creating ventral drainage of abscesses:

- Identify a site that is safe (not in or through an important structure) and most likely to be abscess. You can identify this site through ultrasound, visual inspection (the lowest aspect) and /or palpation (feel for a soft stop). It is ideal if this is ventral but that isn’t always possible. Inject lidocaine for local anesthesia.

- Insert a large gauge needle (at least 18ga for horses, at least 16ga for cattle) through the local block into the abscess to confirm pus. If pus is obtained, a second needle is inserted at least a centimeter away (2-3 cm is better). If this needle also yields pus, connect the two sites via sharp incision with a scalpel blade. If no pus, try again or return to step 1.

- Collect a sample of pus for culture and sensitivity

- Explore the abscess cavity to determine if the incision is ventral enough and/or where a ventral incision should be created. Digital palpation is ideal; sterile probes can also help identify the extent of the abscess cavity and appropriate drainage sites. If needed, the original incision can also be extended to allow better inspection or drainage. Having a finger or probe evaluate the pocket makes this safer.

- Enlarge the incision if needed. Ideally, ventral drainage is created with a big enough incision made to allow the wound to heal from the inside out. *Cattle close holes very quickly – be generous (but safe) with the size of the incision.

- Penrose drains can be used to encourage drainage from wounds but are also irritants and only serve to wick the pus out. Drains should be time limited (use for only a few days). It is often more effective to make a bigger ventral hole rather than trying to use a drain. Penrose drains are not very effective in cattle due to the thickness of the pus.

Pigs – Draining abscesses on pigs kept with other pigs can actually make things worse for the affected pig as the others will root around in the wound. If the welfare of the pig is not impaired, the abscess may be left untreated. If treatment is needed, isolation of the affected pig will help minimize complications.

Abscess management

After the abscess is lanced, it needs to heal from the inside out. The wound can be kept open through flushing or packing (gauze, sugar, honey).

-

- The solution to pollution is dilution. Flush with copious amounts of isotonic fluids; tap water is fine in most of these. Sterile LRS and sterile saline are fine. Hypotonic and hypertonic solutions should be avoided as they cause cellular damage. Adding antibiotics is usually not helpful as most of your antibiotics drain back out again. Creating colored water through other additives is similarly not helpful.

- Diluted iodine based solutions are more effective than strong iodine solutions as the iodine is released and active (weak tea color)

- tincture of iodine is way too strong and is tissue toxic

- examples of iodine based solutions – betadine, povidone iodine

- Most betadine and chlorhexidine solutions are tissue toxic unless very dilute

- Betadine and chlorhexidine should only be infused when they can drain back out, regardless of dilution

- Distilled water is hypotonic and damaging to cells.

- Twice daily flushing is often necessary to keep the abscess from sealing over prematurely

- Keep hydrogen peroxide far away from wounds. It is damaging.

- Diluted iodine based solutions are more effective than strong iodine solutions as the iodine is released and active (weak tea color)

- The wound can be packed with dry or betadine soaked gauze that is pulled out slowly over time

- Honey and sugar are good packing agents in wounds as they help control infection and stimulate granulation tissue formation

- The solution to pollution is dilution. Flush with copious amounts of isotonic fluids; tap water is fine in most of these. Sterile LRS and sterile saline are fine. Hypotonic and hypertonic solutions should be avoided as they cause cellular damage. Adding antibiotics is usually not helpful as most of your antibiotics drain back out again. Creating colored water through other additives is similarly not helpful.

If sterile fluids are needed, a 3 way stop cock and two extension sets can make it much easier to flush a wound or abscess. Just turn the stop cock to fill up the syringe and then turn again to force the fluid out the tubing. The faster but more physical alternative is to put an 18 gauge needle on the end of an extension set and just squeeze.

Antibiotic therapy

Antibiotics are generally not necessary if drainage can be obtained (but many graduate vets have a hard time with this). Antibiotics are indicated if the animal shows signs of systemic infection (fever, white blood cell changes) after drainage is obtained, if ventral drainage is impossible or if vital structures are at risk (eg pleural cavity, mediastinum, abdominal cavity, joint).

Regional antibiotics (including infusion into the abscess) tend to be more effective than systemic antibiotics. Regional antibiotics include infusion into the joint, tendon sheath or local veins with a tourniquet in place to keep the drugs in the region. Many antibiotics cannot readily penetrate an abscess capsule and/or may not be effective in the abscess environment due to pH changes and other factors in the pus. Remember antibiotic choices are limited in food animals and require strict attention to withholding times to protect food safety. If an abscess doesn’t respond, it is more often due to foreign material in the wound than it is to the bacterial infection.

Most wound infections will be inhabited by multiple species of bacteria and should be cultured to determine antibiotic selection if antibiotics are needed (generally antibiotics aren’t needed!). Abscesses relating to infectious organisms are less common but important to identify to prevent further spread.

The majority of bovine abscesses, regardless of cause, will be infected with Trueperella pyogenes (last known as Arcanobacter pyogenes). This agent is sensitive to most antibiotics but creates a thick walled abscess that makes antibiotic penetration difficult. It Is also very hardy in the environment; try to collect the pus during surgery (vs letting it go everywhere) or separate the animal while the abscess is draining.

Common mistakes

-

- Insufficient ventral drainage – not drained, not ventral or not big enough

- Flushing with irritating solutions that make things worse

- Avoid hydrogen peroxide, strong iodine and chlorhexidine solutions

- Contaminating the environment

If the abscess isn’t resolving:

- Is there adequate ventral drainage?

- Is there systemic infection? (eg Streptococcus or Corynebacterium)

- Is there a foreign body or sequestrum?

The abscess over this horse’s shoulder isn’t resolving as ventral drainage is impossible to achieve in this area (the thoracic spines and scapula prevent it). This is a case of fistulous withers. Surgical resection was required to resolve the infection. [Brucella can cause fistulous withers; use caution and culture.]

Camelids can develop spontaneous bone sequestra, particularly in the head. As the body tries to resolve these sequestra, sterile abscesses develop. More often, they develop abscesses in the jaw region from infected teeth. Resolving these abscesses will require removing the tooth, tooth root or bony sequestrum.

Foreign bodies can be left in wounds from the initial trauma (stick) or be added by vets (suture). Remove to resolve the problem!

Key Takeaways

Abscesses are warm, painful and contain pus

- Create ventral drainage

- Flush or pack

- Minimize environmental contamination

- Avoid antibiotics

If abscesses are not resolving, look for a foreign body.

Resources

Bad advice about antibiotic prophylaxis

Treatment of fistulous cranial nuchal bursitis by complete surgical resection in two horses, Equine Vet Educ. 2023;35:e391–e397.

pieces of dead bone that cause persistent draining tracts as the body tries to liquefy them