9.10 Testing Trivers-Willard in humans

So, does the Trivers-Willard hypothesis apply to human populations? In short, it’s complicated. And it’s always more difficult (or really, impossible) to conduct controlled studies in humans. However, there are certainly tantalizing lines of evidence that suggest that even in humans, mothers in good condition may tend to produce more sons than daughters. As merely a few examples:

- A multi-year study of children born to thousands of Danish mothers investigated the impact of stress on offspring sex ratio. The investigators noted that mothers who experienced an extremely stressful “life event” (such as the death of a spouse or child, a cancer diagnosis, etc.) during pregnancy exhibited a lower offspring sex ratio than did their less-stressed counterparts.[1]

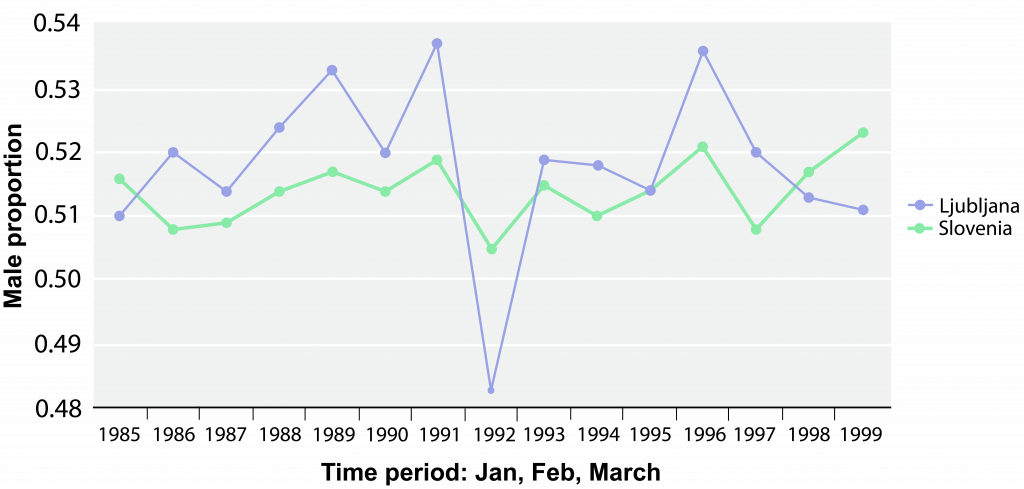

- Stress is high during times of war, and this stress has been hypothesized to be associated with a decline in the M:F sex ratio. For example, in summer 1991, Slovenia engaged in a brief war for independence. The data on human sex ratios in the country and in the capital of Ljubljana, from several years before, during and after, the war, are depicted below.[2]

Check Yourself

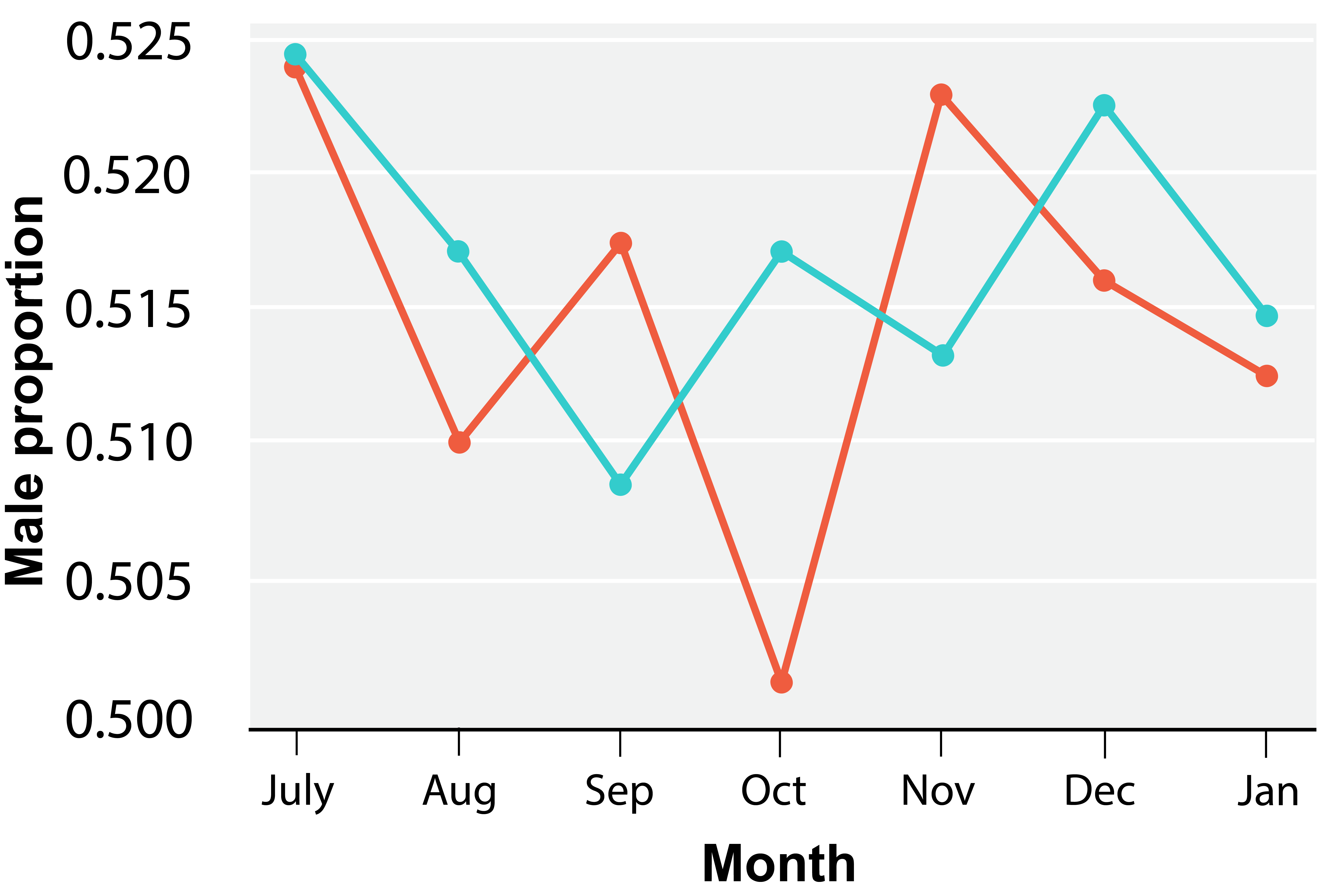

- Stress is also high after natural disasters, and several lines of evidence suggest that enduring an extreme natural disaster can lead to a lowered sex ratio in a population. For example, a catastrophic earthquake shook Kobe, Japan, in January 1995. Consider these data, from the period afterwards, and note the pattern at approximately nine months later. [3]

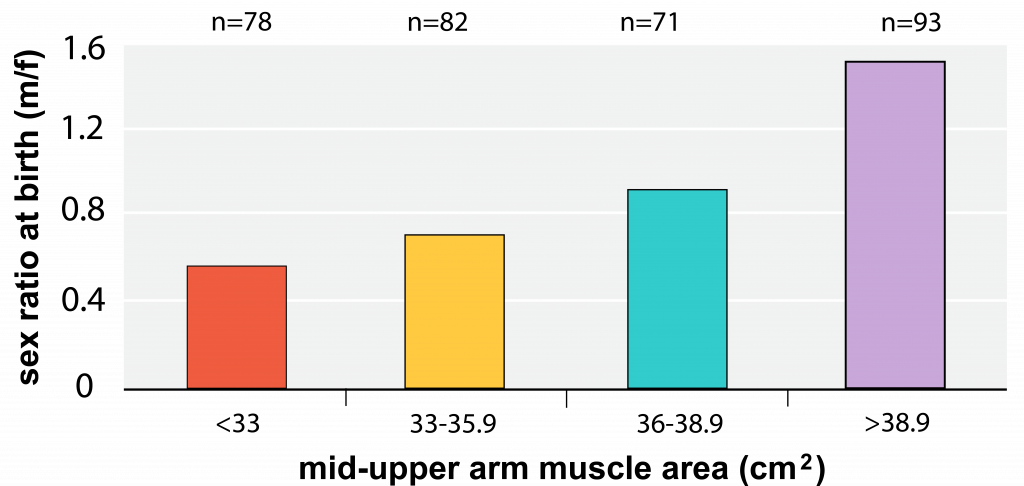

- Another way to measure “condition” is through the mother’s general health. In many human populations, this can be a metric as simple as body weight—that is, does the mother typically get enough to eat? Several studies have examined the relationship between maternal weight and offspring sex ratio. For example, in Mhairi Gibson and Ruth Mace’s study of an agrarian community in southern Ethiopia, they documented a relationship between upper-arm circumference (which is itself a measure of health—i.e., strength, having enough to eat) and offspring sex ratio. [4] Their data is represented here:

Check Yourself

- Hansen, D., Moller, H., & Olsen, J. (1999). Severe periconceptional life events and the sex ratio in offspring: follow up study based on five national registers. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 319 (November 2008), 548–549. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7209.548] ↵

- Hansen, D., Moller, H., & Olsen, J. (1999). Severe periconceptional life events and the sex ratio in offspring: follow up study based on five national registers. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 319(November 2008), 548–549. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7209.548] ↵

- Hansen, D., Moller, H., & Olsen, J. (1999). Severe periconceptional life events and the sex ratio in offspring: follow up study based on five national registers. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 319(November 2008), 548–549. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7209.548 ↵

- Gibson, M. a, & Mace, R. (2003). Strong mothers bear more sons in rural Ethiopia. Proceedings. Biological Sciences / The Royal Society, 270 Suppl (August), S108-9. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2003.0031 ↵