38 Vomiting and Reflux

Pathophysiology

Vomiting is a common non-specific condition that affects small animals, pot bellied pigs and some exotics. Vomiting is not routinely seen in horses, camelids or ruminants.

With vomiting, the stomach, abdominal muscles, and diaphragm contract. The lower esophageal sphincter opens. The palate and epiglottis move up to protect the airway. (see link)

Vomiting comes with a very broad list of differential diagnoses, including both GI disorders (obstruction, ulcers, ileus; primary GI) and secondary disorders such as toxin/infection exposure, abdominal pain, endocrine or intracranial processes (secondary GI). They all work through the vomiting center in the brain.

Primary GI causes

Primary GI refers to cases in which the GI tract itself is involved.

Primary GI disorders that cause vomiting can usually be classified as infiltrative, obstructive, infectious, dysmotility and toxins. Examples include canine gastric dilatation volvulus (GDV), foreign body, gastric ulcers, intussusception, parvoviral enteritis, canine distemper, leptospirosis, internal parasites (stomach worms, roundworms), and hemorrhagic gastroenteritis.

Primary GI is more likely if the animal is not overly sick, has something abnormal on abdominal palpation (foreign body, intussusception) or has significant diarrhea. Generally a CBC, profile and UA are most helpful to rule out a secondary GI disorder.

Some of these animals will need surgery!

Secondary GI causes

Secondary GI refers to causes of GI type clinical signs that are related to organ dysfunction that isn’t the GI tract.

Secondary GI disorders that cause vomiting include renal disease, hepatic disease, pancreatic or endocrine disease, adrenal disease (Addisons), peritonitis, hyperthyroidism, or CNS disease (cortical disease, vestibular disease). Besides organ failure, disorders include pyometra, diabetic ketoacidosis, motion sickness, ear infections, and septicemia.

With secondary GI issues, animals are often sick and generally are normal on abdominal palpation.

Generally, surgery and anesthesia is contraindicated!

Differentiating primary and secondary GI issues

| Primary GI | Secondary GI | |

| History | Dietary indiscretion, dietary changes, missing object | Car ride, not spayed, weight changes, head trauma |

| Physical examination | Pain or masses on abdominal palpation. Otherwise healthy | Sick, fever, thyroid enlargement |

| Radiographs (plain or contrast) | Check for foreign bodies or masses | Check for enlarged uterus or liver |

| Fecal/UA | Check for parasites | Check for kidney issues |

| Blood work | Dehydration | Check for systemic disease, hyperthyroidism |

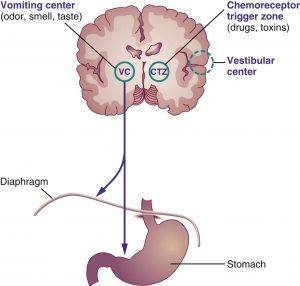

Vomiting reflex

All vomiting stimulants act through the vomiting center in the brain.

The 5 main neurotransmitters involved in the vomiting pathway:

- muscarinic (vagus nerve)

- dopamine

- histamine

- serotonin

- neurokinin

Maropitant (CereniaR) is a highly effective drug in small animals, blocking Substance P (NK-1) receptors in multiple sites. Ondansetron is usually the second choice.

Reflux

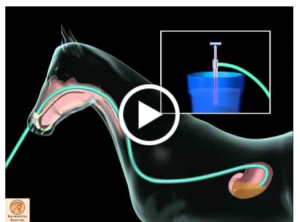

Horses can’t vomit but still have the same fluid backup. Due to the strong lower esophageal sphincter, the stomach will often rupture before the animal can actually vomit. When a horse is colicky, it can be life saving to pass a stomach tube and relieve the fluid. Instead of vomiting, we say horses are refluxing.

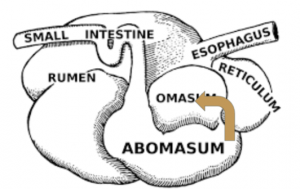

Cattle and camelids don’t usually vomit. In these animals the fluid that would be vomited moves into the omasum, reticulum and/or rumen (cattle) and C2 and C1 (camelids).

Electrolyte and acid base changes

The stomach contents are acidic. If the vomitus/reflux is due to an upper GI problem, the animal loses hydrogen and chloride. Ruminants with abomasal outflow obstruction still lose the HCl but it ends up in the rumen. All animals with an upper GI obstruction tend to hypochloremic. Cattle usually have hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis. Dehydration makes animals acidotic so small animals may not show the alkalosis but may actually be acidotic.

Differentiating dysphagia, regurgitation and vomiting

| Difficulty chewing or swallowing? | Retching noises? | Abdominal effort? | |

| Dysphagia | yes | no | no |

| Regurgitation | no | no | no |

| Vomiting | no | yes | yes |

History and other clinical signs can be useful.

Diagnostics for vomiting

Diagnostics are often NOT performed for acute cases of vomiting. Supportive care is provided and diagnostics only performed if the animal doesn’t respond. One common “test” is response to maropitant (antinausea drug). Maropitant usually controls vomiting due to brain or non-GI lesions. If the animal continues vomiting, this is considered an indication of a surgical lesion.

Key factors:

| Primary GI | Secondary GI | |

| History | Head trauma | |

| Physical examination | Abnormal abdominal palpation. Otherwise healthy | Sick. Fever. |

| Lab work | Dehydration | Abnormalities |

| Response to maropitant | Not if surgical | Yes |

Diagnostics for severe or chronic vomiting might include

SA Tier 1

- Fecal evaluation –internal parasites

- CBC or PCV/TPP- hydration status, signs of infection or inflammation

- UA-urine specific gravity, UTI, proteinuria, glucosuria

- Chemistry – organ function (kidney, liver, pancreas), electrolyte levels

- Baseline cortisol – Addisons in dogs

- Blood gas/istat- electrolyte, acid base status

- T4-hyperthyroidism- cats > 7yo

- Abdominal radiographs-foreign body, gas distension in stomach/SI/LI, feed/fecal obstruction, lymphadenopathy, intussusception

- Thoracic radiographs- pneumonia

- Parvo SNAP test- kittens and puppies with diarrhea and vomiting

SA Tier 2

- ACTH stim-adrenal insufficiency

- Abdominal ultrasound/AFAST-free fluid, intestinal activity, abnormal densities, intestinal wall thickness

- Contrast upper GI study

- Bile acids, cPLI/fPLI

SA Tier 3

- CT -cranial, thoracic or abdominal disease/masses

- Endoscopy- esophageal/gastric ulceration/obstruction

- Surgery– abdominal masses, obstruction

LA diagnostics

- Check for reflux by passing a tube into the stomach

- Check rumen pH to determine if it is lower than usual due to the addition of acidic stomach contents

Therapy

Drugs are available to block each part of the vomiting pathway in small animals. In veterinary medicine, the first line agent is typically maropitant.

Maropitant blocks the NK-1 receptors, keeping substance P from binding and starting the vomiting process.

Odansetron blocks 5-HT3 serotonergic receptors and is used if maropitant isn’t working.

Metoclopramide is used, particularly if there is a motility disorder, as it stimulates gastric emptying. Metoclopramide blocks dopaminergic function in part.

Antihistamines can also be useful but have sedative effects as well.

In most clinical situations vomiting is acute, self-limited, lasting for several hours to days. Acute vomiting is often treated supportively. Chronic vomiting represents symptoms present for greater than 7-10 days or unresponsive to initial therapy; such patients need a more involved diagnostic evaluation.

In addition to identifying the underlying cause of the vomiting, complications of vomiting such as dehydration, acid-base and electrolyte abnormalities, gastroesophageal-reflux disease (GERD), weight loss and aspiration pneumonia should be identified early in the patient assessment.

GERD occurs due to damage of the esophagus by refluxed (vomited) gastric juices. Aspiration pneumonia due to inhalation of vomitus. As stomach and biliary fluids are lost, animals may develop related electrolyte and acid-base changes. Saliva contains large amounts of bicarbonate. If the fluid lost is primarily saliva, the animal will become acidotic.

Fix electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities.

Supportive care for vomiting may include

- No food for 6-12 hours, then an easily digestible diet (boiled chicken and rice, prescription diets such as I/D, EN or Gastrointestinal diets)

- Fluids

- Antiemetics (maropitant)

- Prokinetics (metoclopramide)

- Probiotics

- Antacid treatment

- H2 blockers (famotidine, ranitidine)

- Proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole)

- Coating agents (sucralfate)

- Antimicrobials

- Psyllium

- Specific antitoxins

- Primary disease related therapy (eg insulin)

Pharmacological stimulation of vomiting

Apomorphine is used to stimulate vomiting when an animal has ingested something it shouldn’t. Apomorphine works by stimulating dopamine receptors. Dilute hydrogen peroxide can also be used in certain species; however it is basically being used for its toxic effects, ideally at a low dose.

Ropinirole ophthalmic solution (Clevor) has recently been approved by the FDA to induce vomiting in dogs. This drug is a dopamine agonist, as well.

Vomiting should not be induced if it is more than 1-2 hours after eating (the substance has left the stomach) or if coming back up would be just as bad (alkali or corrosive substances, etc).

Key Takeaways

- With vomiting, the stomach, abdominal muscles and diaphragm contract. The lower esophageal sphincter relaxes. Abdominal muscle contraction is a key factor that differentiates vomiting from regurgitation and dysphagia.

- All vomiting is initiated by the vomiting center. The major neurotransmitters are 5HT3, NK-1 and dopamine. The vagal nerve plays a role in sending signals to the vomiting center.

- Vomiting can occur due to primary GI issues (problems with the GI tract) or secondary GI issues (problems with other organs).

Resources

Vomiting in pets – WSU CVM

Chronic vomiting in cats – JAAHA, 2016 – nice outline of approach

Symptomatic Management of Primary Acute Gastroenteritis, Todays Vet Pract 2015- SA general; lots of info about therapies

Digestive system part 2 – an additional look at digestion or skip to 8:50 to see the vomiting part

Physiology of vomiting – video – more details but good

Dog vomiting causes and treatment – Purina blog

Colic in horses when is surgery necetssary – The Horse article

Approach to diagnosis and therapy of the vomiting patient, Today’s Veterinary Practice March/April 2013 – nice review of pathophysiology, drugs and common causes

Just for fun

Vomiting vs regurgitation with Dr. Foley – animated description

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis – occasionally seen in small animals; we do get similar conditions due to tumors and adhesions ; good anatomy/physio review

Vomiting in pigs– the pig site typically has good info!

Apomorphine administration -> vomiting; useful for toxins that have recently been ingested

Inducing vomiting, VSPN

Pharmacology – Antiemetics– more drugs than vets typically use but good info

How does my stomach work – good explanation of esophageal reflux disease and hiatal anatomy

Physiology of vomiting (dogs) – fancier than it needs to be

Nausea and vomiting (people); shorter than some others and easy to understand