31 Gastric activity and function

The stomach is designed to hold food, destroy microbes and start the process of digestion.

Food storage

As food enters the stomach, the stomach relaxes in a process called receptive relaxation or accommodation. The process is mediated by the vagal nerve and allows for the storage of more food. Predators tend to have larger stomachs with more relaxation capability as they may not eat frequently. Grazers such as horses have smaller stomachs relative to body size.

Acid production

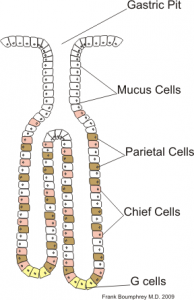

Stimulated parietal cells produce hydrochloric acid (HCl) via a proton pump, creating a very acidic environment. This helps to kill any microbes that entered on or with the food.

Stimulated parietal cells produce hydrochloric acid (HCl) via a proton pump, creating a very acidic environment. This helps to kill any microbes that entered on or with the food.

The acid proton pump is stimulated by a combination of acetylcholine, histamine and gastrin. Vagal stimulation and release of acetylcholine occurs with swallowing and gastric distension. G cells produce gastrin in response to stretching of the stomach wall, protein in the chyme, and higher gastric pH. Enterochromaffin cells produce histamine in response to gastrin and pituitary peptides.

Activation of the pump is summative – the activation is strongest when all three compounds (acetylcholine, histamine and gastrin) are binding compared to when only one or two compounds are binding the pump.

The proton pump is inhibited by prostaglandins, antihistamines, and somatostatin.

The HCl also activates pepsinogen produced by the chief cells. Pepsinogen is turned into pepsin and can begin protein digestion.

The stomach also contains mucin cells which produce mucous to protect the stomach wall from the acid production.

Pepsin production

Once the environment is acidic, pepsinogen is converted to pepsin. Pepsin starts breaking down proteins into peptides. Once proteins are small enough, the stomach will allow them to move into the duodenum for further digestion.

Stomach motility and emptying

The stomach does contract to grind and mix the food.

As food is broken into smaller particles, the pylorus opens to allow the “chyme” to move into the duodenum.

The stomach empties faster with liquid contents (especially isotonic liquids) and with large meals (gastric distension).

Mostly things delay stomach emptying. The stomach empties only when the duodenal environment suggests that the prior meal has moved down the GI tract. The presence of acid, protein byproducts and fats in the duodenum mean the last “meal” is still in the duodenum and there is no room for more. This information is sent back to the pylorus, preventing emptying of more food.

When the pH is elevated (from the pancreatic secretions) and minimal food byproducts are present in the duodenum and if the stomach contents are small enough, the pylorus will push more gastric content into the duodenum and the cycle starts again.

Cholecystokinin and secretin delay gastric emptying as their release from the pancreas and SI are due to the presence of feed stuffs (CCK released in the presence of lipids and tryptophan) and excessive stomach acid (secretin).

Other factors that can delay stomach emptying include pregnancy, stress, pain and drugs.

Key Takeaways

The gastric fundus relaxes when a meal is anticipated. This allows it to fill without increasing tone. The stomach empties in response to changes in gastric and duodenal contents. Large meals and fluids stimulate emptying. Everything else delays gastric emptying.

Resources

The parietal cell acid secretion – Colostate vivo

How HCl is formed and secreted – animation

Gastric acid physiology – watch 2:30-6:30 in particular; rest is good too

What the stomach cells do – gastrin, parietal, chief cells, g cells, oh my

Physio of the stomach and gastric juices -advanced info about digestion

Just for fun

Upper GI movies – stomach peristalsis