41 Enteritis and colitis

Pathophysiology

Enteritis is inflammation of the small intestine. Colitis is inflammation of the large intestine. Enterocolitis is both.

Inflammation can lead to cell damage and infiltration of inflammatory cells. Inflammatory cell infiltration will lead to thickening of the villi. Release of inflammatory cell mediators can lead to cellular and tissue destruction.

Both enteritis and colitis can result in fluid loss and diarrhea.

Enteritis is also associated with bloating as the food stuff that isn’t absorbed in the SI may actually be digestible by the colonic bacteria.

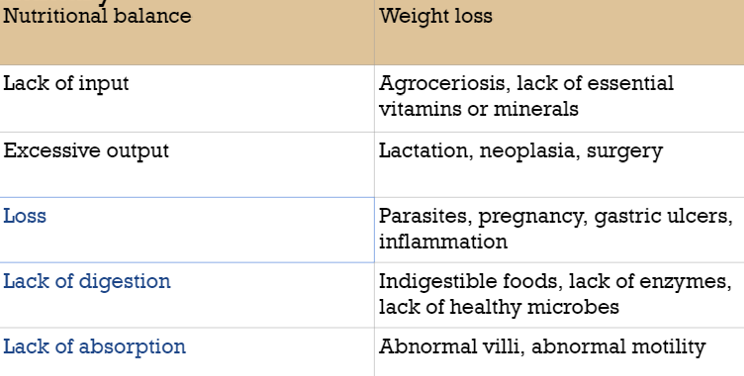

Enteritis also results in weight loss and malnutrition:

- With a thickened or destroyed villus, nutrients do not always make it into the lacteals and vasculature. Movement of nutrients is due to passive diffusion and requires a very thin villus.

- Protein is often lost into the gut lumen with inflammation or gut damage, particularly due to loss of tight junctions between cells.

- Maldigestion occurs when villi do not produce the normal peptidases or with pancreatic insufficiency. Malabsorption occurs when thickened or damaged villi do not absorb fluid or nutrients properly.

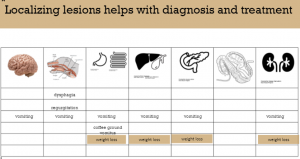

Diagnostics

Gut inflammation can lead to diarrhea or pain signs. Many affected animals have weight loss accompanied by hypoproteinemia (low blood protein).

Low protein

Low protein is often associated with enteritis. Low protein can occur due to limited production (liver) or loss (gut, skin, kidneys). Diagnostic testing to rule out liver and kidney dysfunction can strongly indicate gut loss. GI loss of protein can be difficult to identify since the protein can be digested and broken down into peptides and amino acids. These breakdown products can be absorbed in the SI or utilized by the microbes.

Elevated fecal alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor

This is a protein that is lost with other proteins but, because it inhibits proteinases, does not get destroyed. Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor can be measured in the feces to identify gut protein loss.

Low blood nutrients

Low levels of glucose and other nutrients can indicate maldigestion. Ruling out exocrine pancreatic issues is recommended. We can also measure gastrin levels.

Low levels of folate (vitamin B9) generally indicate malabsorption as high levels are present in most diets.

D-xylose or glucose absorption tests can also be used. Digestion is not required, so blood levels of xylose or glucose directly reflect absorption. D-xylose or glucose absorption is abnormal with malabsorption but normal with pancreatic disease.

Imaging

Ultrasound or contrast radiographs can identify thickened intestinal walls.

Enteritis/colitis therapy

Therapy is often supportive.

Fluids and intravenous protein supplementation are often required. Electrolyte therapy may be needed.

Antibiotics may be used for particular disease (eg Lawsonia) and to minimize bacterial translocation.

Anti-inflammatory therapy may be indicated.

The gut needs nutrition too; easily digestible foodstuffs are indicated.

-

- Treat dehydration – oral rehydration mixes can help force fluid back out of the lumen; sicker animals may need intravenous fluids

- We use salt and glucose to work with the transport mechanisms to encourage movement of water from the bowel back into the bloodstream. These work when the enterocytes are still function (eg with secretory diarrheas). The most common use is in calves with E coli diarrhea.

- Treat electrolyte and acid-base disturbances – most animals become acidotic and need an oral alkalinizing agent (acetate, citrate, bicarbonate) or fluid adjustments

- Restore oncotic pressure – give plasma etc if needed

- Clean and protect the perineum (diaper cream)

- Deworm any likely suspects

- Treat endotoxemia with NSAIDs, polymyxin B, etc

- Treat pain

- Administer gut protectants (pepto bismol, kaopectate, biosponge)

- Potentially give antibiotics

- Potentially give motility modifiers to allow more absorption; contraindicated if infective agents!

- Loperamide (opioid type) and buscopan (anticholinergic agent) have been used to slow motility and enhance water absorption. With diarrhea related to organisms, out is generally better than in and we avoid these agents.

- Bland diet (I/D; no grain; etc)

- Provide oncotic pressure

- Ice feet to prevent laminitis in horses

- Treat dehydration – oral rehydration mixes can help force fluid back out of the lumen; sicker animals may need intravenous fluids

Key Takeaways

- The small intestine is responsible for most of the GI tract fluid absorption

- Obstruction of the SI leads to dehydration, electrolyte derangements, and vomiting and/or reflux

- Digestion and absorption are primary roles of the SI. Abnormalities of the SI lead to low protein and weight loss.

- Protein loss through the bowel leads to elevated fecal alpha-1 proteinase levels.

- Maldigestion is indicated by low gastrin, lipase and/or trypsin levels

- Malabsorption can be detected by low folate levels and/or low glucose absorption

Resources

Symptomatic Management of Primary Acute Gastroenteritis, Todays Vet Pract 2015- SA general; lots of info about therapies

Diagnosis of small intestinal disorders in dogs and cats, VCNA 2013 – inflammatory bowel disease and more

Integrated function – the intestinal phase – includes crypt cell function and general overview

Secretion in the small intestine- another briefer look at secretory action

Fecal alpha1-proteinase inhibitor concentration in dogs with chronic gastrointestinal disease– 2003 article

Malabsorption syndromes in small animal- Merck manual

Lawsonia in horses – web page

Diagnostic testing for SI disorders– Battlab