52 Gastric dysfunction

Gastritis, gastric obstruction and gastric emptying issues

The stomach can have issues. Gastric ulcers are discussed in a different chapter. Gastritis is common and can cause motility disorders, vomiting and pain. Animals can develop gastric impactions, emptying disorders, volvuluses and gastric foreign bodies (toys, bones, bezoars).

Dogs, cattle and small ruminants are fairly indiscriminate eaters and commonly have foreign bodies in the stomach (forestomach in ruminants). Generally these require surgery. Ruminants can eat sharp objects that puncture the reticulum, creating local or diffuse peritonitis. The heart sits on just the other side of the diaphragm, making these animals also prone to pericarditis and pleuritis.

Gastric impactions in horses can be related to poor motility (Friesians are prone) and to dehydration. Horses that eat fresh cut grass can end up with gastric impactions and/or extensive gas due to fermentation. Horses don’t usually eat things they shouldn’t but occasionally develop gastric foreign bodies. Persimmon seeds can be an issue. Occasionally stomach tubes break and parts end up in the stomach. Stomach tube breakage is most common in cold climates.

All species can develop tumors that lead to gastric obstruction.

Gastric “dislocation” is possible is dogs and ruminants. Dogs can develop gastric displacements and gastric volvulus while ruminants (particularly cattle) can develop abomasal displacements or abomasal volvulus. These movements will cause gastric obstruction and distension.

Clinical signs

Animals with gastric distension will show signs of pain and anorexia (lack of interest in food).

Gastric distension can be visible in dogs. It is not typically visible in horses or ruminants unless it associated with abomasal displacement in cattle. [Rumen distension is visible as bloat. Abomasal displacement can lead to some filling of the paralumbar fossa.]

Animals with gastric distension may show vomiting, shock and respiratory changes due to pressure on the diaphragm and impaired venous return. Death can occur.

Horses with gastric distension need to have a nasogastric tube passed to check for reflux or the stomach is likely to rupture.

Small animals with gastric obstruction will typically be vomiting frequently. Vomitus is often white or clear due to lack of bile.

Small animals with gastritis are often vomiting but vomitus is often bile colored (greenish or yellowish).

Diagnostics

Endoscopy can be helpful in larger animals to identify obstructions and ulcers. Ultrasound may show gastric distension or gastric emptiness but is not often helpful in identifying motility patterns. Breath hydrogen levels and acetaminophen absorption are used in research studies.

In horses, reflux can be assessed for pH (lower with gastric outflow obstruction). In cattle, rumen fluid can be checked for chloride level and pH (elevated chloride and lowered pH with gastric outflow obstruction).

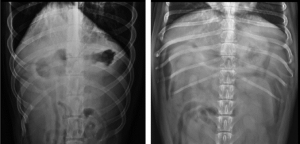

Gastric function can be evaluated by contrast radiographs in smaller animals. The stomach can be relatively distended in normal animals but should change over time.

This is abnormal gastric distension

Key Takeaways

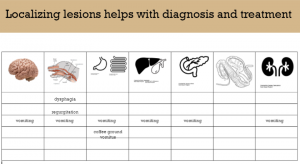

- Vomitus color can help localize lesions and identify upper GI bleeding.

- Gastric distension can lead to shock and death

- In cattle, rumen fluid values can identify abomasal backflow.

- To prevent gastric rupture, horses need to have a nasogastric tube passed when they show signs of colic.

The abomasum, UGA free ibook