12.2 Understanding Financial Statements

Learning Objectives

- Understand the function of the income statement.

- Understand the function of the balance sheet.

- Understand the function of the statement of owner’s equity.

We hope that, so far, we’ve made at least one thing clear: If you’re in business, you need to understand financial statements. For one thing, the law no longer allows high-ranking executives to plead ignorance or fall back on delegation of authority when it comes to taking responsibility for a firm’s financial reporting. In a business environment tainted by episodes of fraudulent financial reporting and other corporate misdeeds, top managers are now being held accountable (so to speak) for the financial statements issued by the people who report to them. For another thing, top managers need to know if the company is hitting on all cylinders or sputtering down the road to bankruptcy. To put it another way (and to switch metaphors): if he didn’t understand the financial statements issued by the company’s accountants, an executive would be like an airplane pilot who doesn’t know how to read the instrument in the cockpit—he might be able keep the plane in the air for a while, but he wouldn’t recognize any signs of impending trouble until it was too late.

The Function of Financial Statements

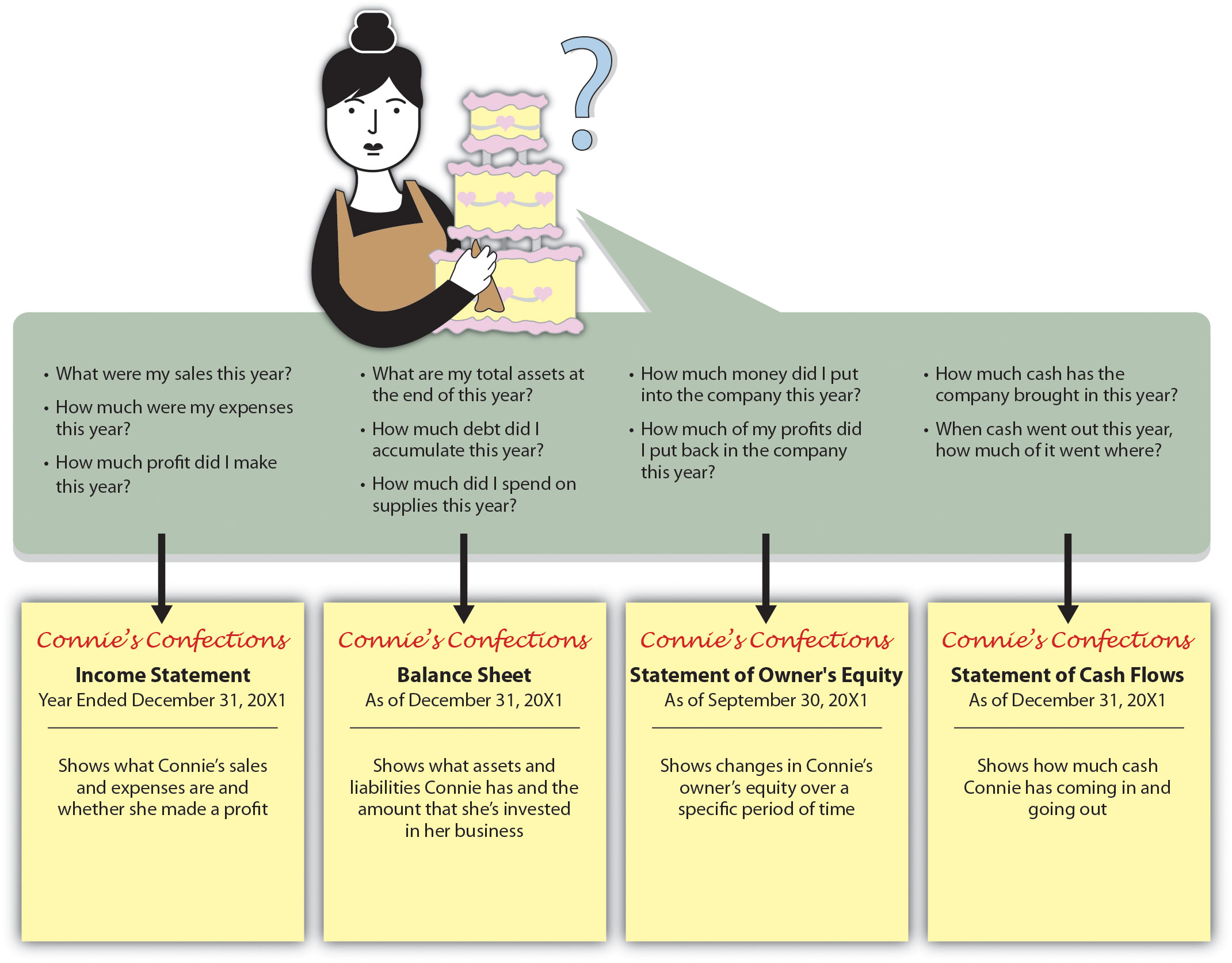

Put yourself in the place of the woman in Figure 12.4 “What Connie Wants to Know”. She runs Connie’s Confections out of her home. She loves what she does, and she feels that she’s doing pretty well. In fact, she has an opportunity to take over a nearby store at very reasonable rent, and she can expand by getting a modest bank loan and investing some more of her own money. So it’s decision time for Connie: She knows that the survival rate for start-ups isn’t very good, and before taking the next step, she’d like to get a better idea of whether she’s actually doing well enough to justify the risk. As you can see, she has several pertinent questions. We aren’t privy to Connie’s finances, but we can tell her how basic financial statements will give her some answers1.

Toying with a Business Idea

We know what you’re thinking: It’s nice to know that accounting deals with real-life situations, but while you wish Connie the best, you don’t know enough about the confectionary business to appreciate either the business decisions or the financial details. Is there any way to bring this lesson a little closer to home? Besides, while knowing what financial statements will tell you is one thing, you want to know how to prepare them.

Agreed. So let’s assume that you need to earn money while you’re in college and that you’ve decided to start a small business. Your business will involve selling stuff to other college students, and to keep things simple, we’ll assume that you’re going to operate on a “cash” basis: you’ll pay for everything with cash, and everyone who buys something from you will pay in cash.

A Word about Cash. You probably have at least a little cash on you right now—some currency, or paper money, and coins. In accounting, however, the term cash refers to more than just paper money and coins. It also refers to the money that you have in checking and savings accounts and includes items that you can deposit in these accounts, such as money orders and different types of checks.

Your first task is to decide exactly what you’re going to sell. You’ve noticed that with homework, exams, social commitments, and the hectic lifestyle of the average college student, you and most of the people you know always seem to be under a lot of stress. Sometimes you wish you could just lie back between meals and bounce a ball off the wall. And that’s when the idea hits you: Maybe you could make some money by selling a product called the “Stress-Buster Play Pack.” Here’s what you have in mind: you’ll buy small toys and other fun stuff—instant stress relievers—at a local dollar store and pack them in a rainbow-colored plastic treasure chest labeled “Stress-Buster.”

And here’s where you stand: You have enough cash to buy a month’s worth of plastic treasure chests and toys. After that, you’ll use the cash generated from sales of Stress-Buster Play Packs to replenish your supply. Each plastic chest will cost $1.00, and you’ll fill each one with a variety of five of the following toys, all of which you can buy for $1.00 each:

- A happy face stress ball

- A roomarang (an indoor boomerang)

- Some silly putty

- An inflatable beach ball

- A coil “slinky” spring

- A paddle-ball game

- A ball for bouncing off walls

You plan to sell each Stress-Buster Play Pack for $10 from a rented table stationed outside a major dining hall. Renting the table will cost you $20 a month. Because your own grades aren’t what your parents and the dean would like them to be, you decide to hire fellow students (trustworthy people with better grades than yours) to staff the table at peak traffic periods. They’ll be on duty from noon until 2:00 p.m. each weekday, and you’ll pay them $6 an hour. Wages, therefore, will cost you $240 a month (2 hours × 5 days × 4 weeks = 40 hours × $6). Finally, you’ll run ads in the college newspaper at a monthly cost of $40. Thus your total monthly costs will amount to $300 ($20 + $240 + $40).

The Income Statement

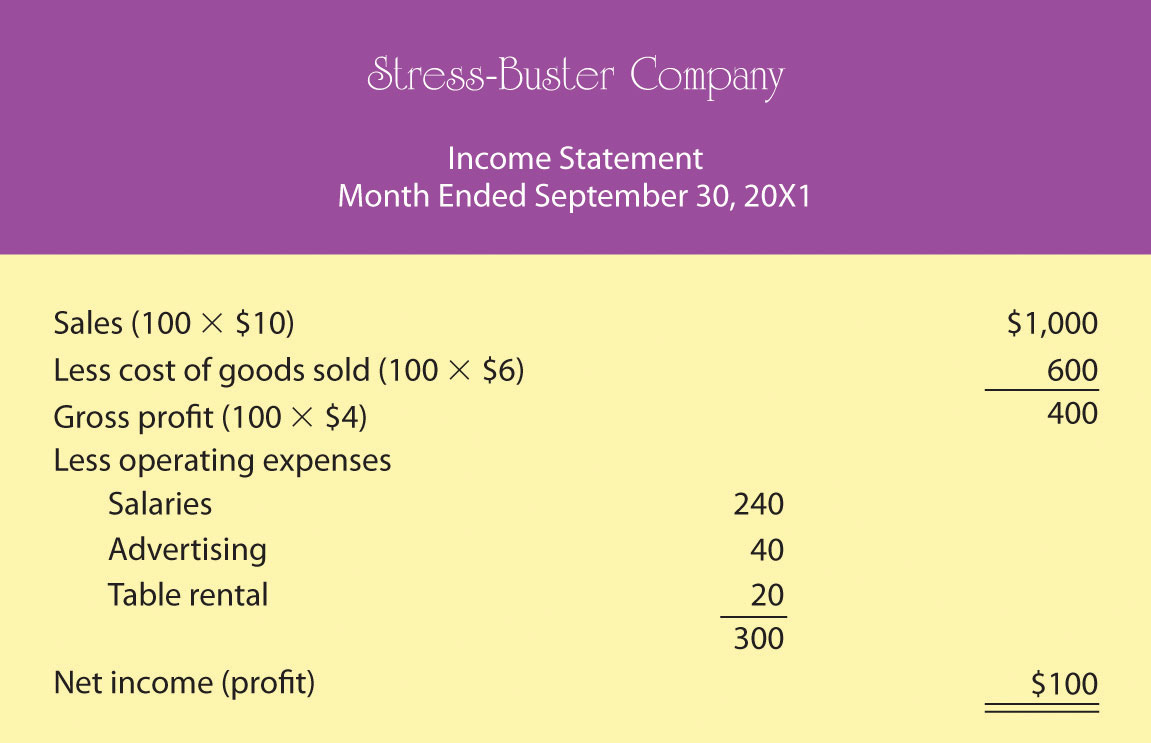

Let’s say that during your first month, you sell one hundred play packs. Not bad, you say to yourself, but did I make a profit? To find out, you prepare an income statement showing revenues, or sales, and expenses—the costs of doing business. You divide your expenses into two categories:

- Cost of goods sold: the total cost of the goods that you’ve sold

- Operating expenses: the costs of operating your business except for the costs of things that you’ve sold

Now you need to do a little subtracting:

- The positive difference between sales and cost of goods sold is your gross profit or gross margin.

- The positive difference between gross profit and operating expenses is your net income or profit, which is the proverbial “bottom line.” (If this difference is negative, you took a loss instead of making a profit.)

Figure 12.5 “Income Statement for Stress-Buster Company” is your income statement for the first month. (Remember that we’ve made things simpler by handling everything in cash.)

Did You Make Any Money?

What does your income statement tell you? It has provided you with four pieces of valuable information:

- You sold 100 units at $10 each, bringing in revenues or sales of $1,000.

- Each unit that you sold cost you $6—$1 for the treasure chest plus 5 toys costing $1 each. So your cost of goods sold is $600 (100 units × $6 per unit).

- Your gross profit—the amount left after subtracting cost of goods sold from sales—is $400 (100 units × $4 each).

- After subtracting operating expenses of $300—the costs of doing business other than the cost of products sold—you generated a positive net income or profit of $100.

What If You Want to Make More Money?

You’re quite relieved to see that you made a profit during your first month, but you can’t help but wonder what you’ll have to do to make even more money next month. You consider three possibilities:

- Reduce your cost of goods sold (say, package four toys instead of five)

- Reduce your operating costs (salaries, advertising, table rental)

- Increase the quantity of units sold

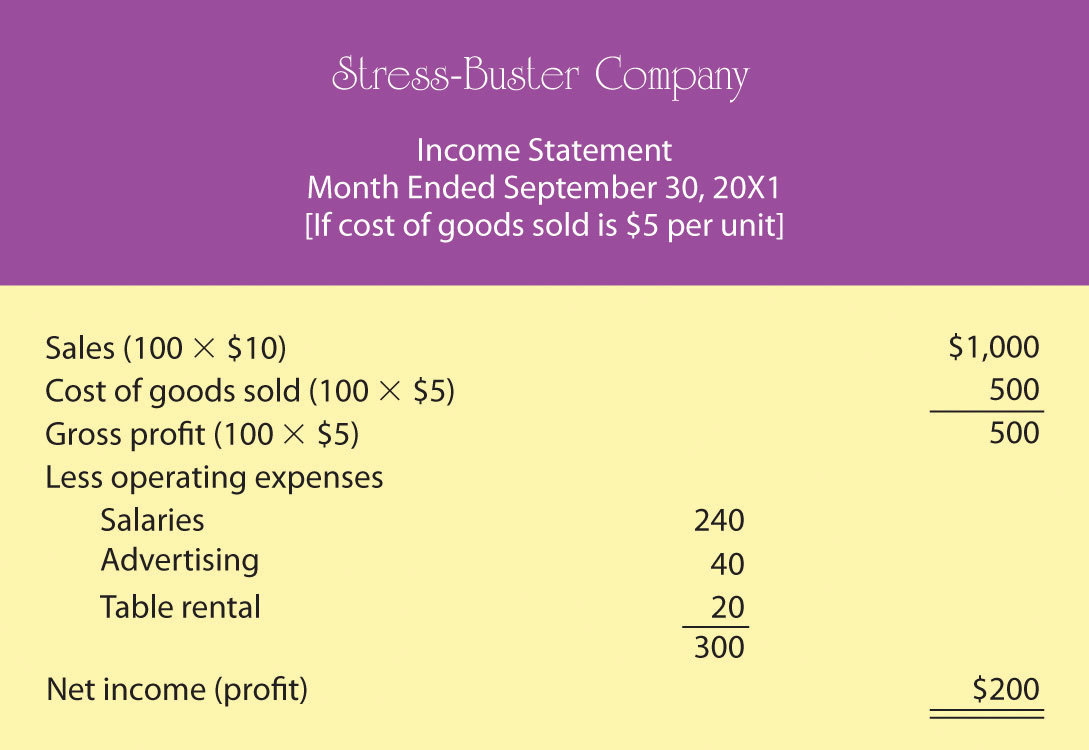

In order to consider these possibilities fully, you need to generate new income statements for each option. And to do that, you’ll have to play a few “what-if” games. Because possibility #1—packaging four toys instead of five—is the most appealing, you start there. Your cost of goods sold would go down from $6 to $5 per unit (4 toys at $1 each + 1 plastic treasure chest at $1). Figure 12.6 “Proposed Income Statement Number One for Stress-Buster Company” is your hypothetical income statement if you choose this option.

Possibility #1 seems to be a good idea. Under this scenario, your income doubles from $100 to $200 because your per-unit gross profit increases by $1 (and you sold 100 stress packs). But there may be a catch: If you cut back on the number of toys, your customers might perceive your product as a lesser value for the money. In fact, you’re reminded of a conversation that you once had with a friend whose father, a restaurant owner, had cut back on the cost of the food he served by buying less expensive meat. In the short term, gross profit per meal went up, but customers eventually stopped coming back and the restaurant nearly went out of business.

Thus you decide to consider possibility #2—reducing your operating costs. In theory, it’s a good idea, but in practice—at least in your case—it probably won’t work. Why not? For one thing, you can’t do without the table and you need your workers (because your grades haven’t improved, you still don’t have time to sit at the table yourself). Second, if you cut salaries from, say, $6 to $5 an hour, you may have a hard time finding people willing to work for you. Finally, you could reduce advertising costs by running an ad every two weeks instead of every week, but this tactic would increase your income by only $20 a month and could easily lead to a drop in sales.

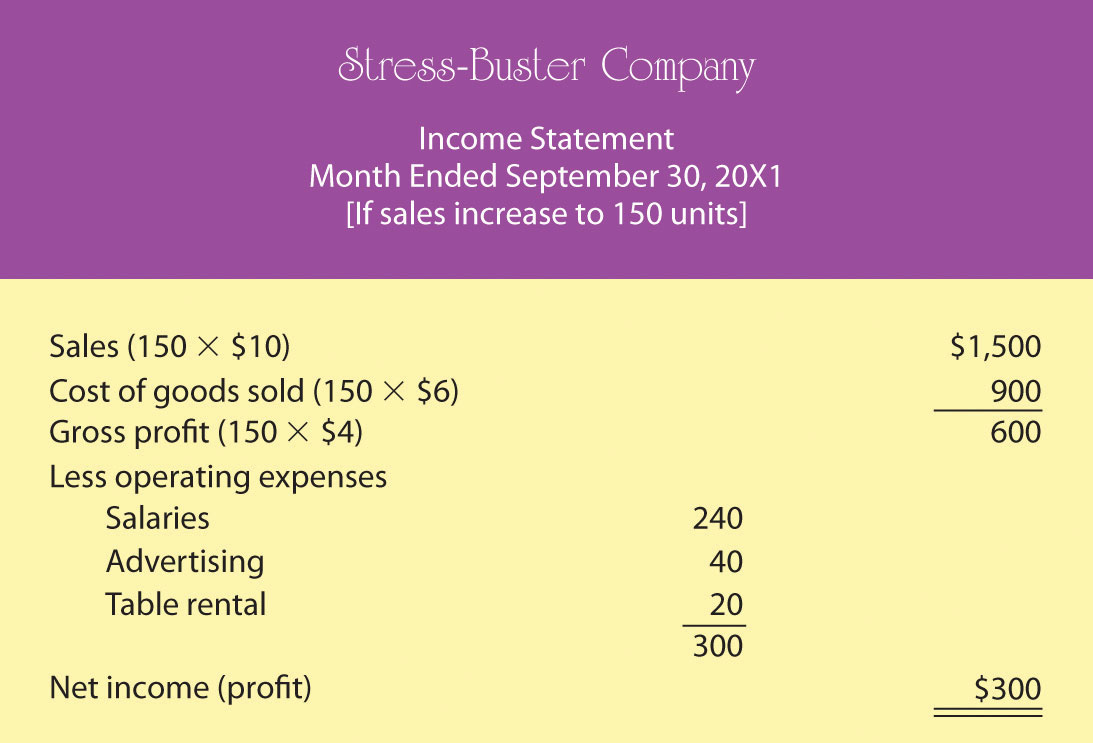

Now you move on to possibility #3—increase sales. The appealing thing about this option is that it has no downside. If you could somehow increase the number of units sold from 100 Stress-Buster packs per month to 150, your income would go up, even if you stick with your original five-toy product. So you decide to crunch some numbers for possibility #3 and come up with the new “what-if” income statement in Figure 12.7 “Proposed Income Statement Number Two for Stress-Buster Company”.

As you can see, this is an attractive possibility, even though you haven’t figured out how you’re going to increase sales (maybe you could put up some eye-popping posters and play cool music to attract people to your table. Or maybe your workers could attract buyers by demonstrating relaxation and stress-reduction exercises).

Breakeven Analysis

Playing these what-if games has started you thinking: is there some way to figure out the level of sales you need to avoid losing money—to “break even”? This can be done using breakeven analysis. To break even (have no profit or loss), your total sales revenue must exactly equal all your expenses (both variable and fixed). For a merchandiser, like a hypothetical one called The College Shop, this balance will occur when gross profit equals all other (fixed) costs. To determine the level of sales at which this will occur, you need to do the following:

1. Determine your total fixed costs, which are so called because the total cost doesn’t change as the quantity of goods sold changes):

- Fixed costs = $240 salaries + $40 advertising + $20 table = $300

2. Identify your variable costs. These are costs that vary, in total, as the quantity of goods sold changes but stay constant on a per-unit basis. State variable costs on a per-unit basis:

- Variable cost per unit = $6 ($1 for the treasure chest and $5 for the toys)

3. Determine your contribution margin per unit: selling price per unit – variable cost per unit:

- Contribution margin per unit = $10 selling price – $6 variable cost per unit = $4

4. Calculate your breakeven point in units: fixed costs ÷ contribution margin per unit:

- Breakeven in units = $300 fixed costs ÷ $4 contribution margin per unit = 75 units

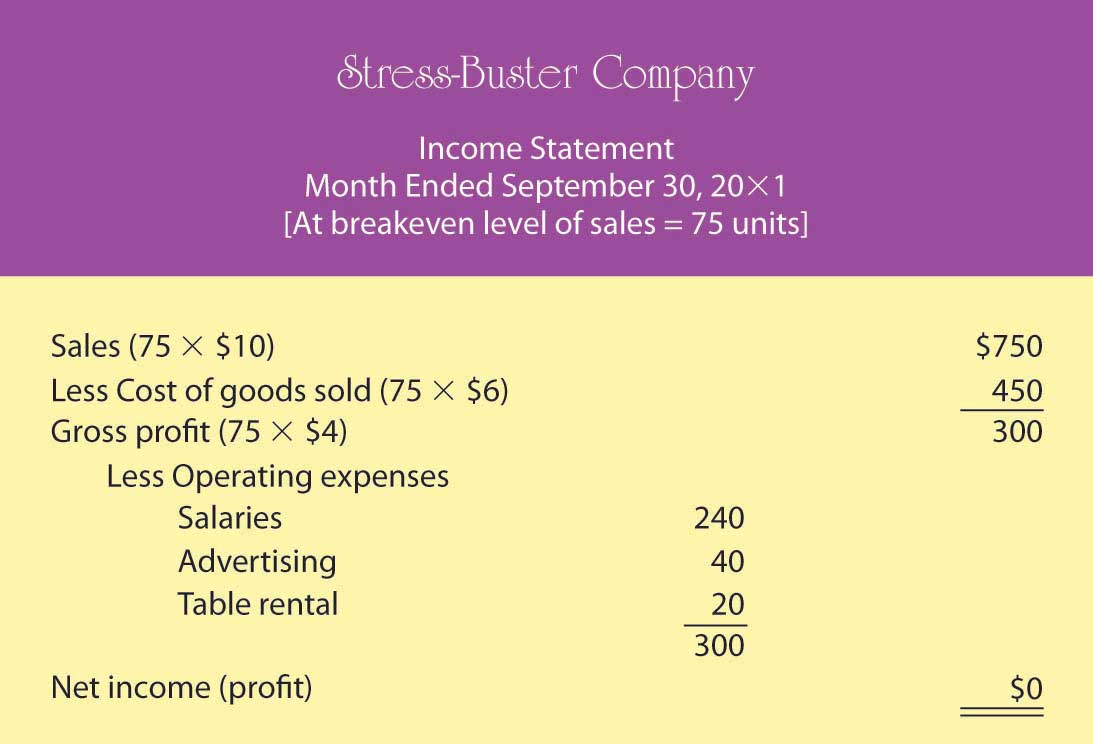

Your calculation means that if you sell 75 units, you’ll end up with zero profit (or loss) and will exactly break even. To test your calculation, you can prepare a what-if income statement for 75 units in sales (which is your breakeven number of sales). The resulting statement is shown in Figure 12.8 “Proposed Income Statement Number Three for Stress-Buster Company”.

What if you want to do better than just break even? What if you want to earn a profit of $200 next month? How many Stress-Buster Pack units would you need to sell? You can find out by building on the results of your breakeven analysis. Note that each additional sale will bring in $4 (contribution margin per unit). If you want to make a profit of $200—which is $200 above your breakeven point—you must sell an additional 50 units ($200 desired profit divided by $4 contribution margin per unit) above your breakeven point of 75 units. If you sell 125 units (75 breakeven units + the additional 50), you’ll make a profit of $200 a month.

As you can see, breakeven analysis is rather handy. It enables you to determine the level of sales that you must reach to avoid losing money and the level of sales that you have to reach to earn a profit of $200. Such information will help you plan for your business. For example, knowing you must sell 125 Stress-Buster Packs to earn a $200 profit will help you decide how much time and money you need to devote to marketing your product.

The Balance Sheet

Your balance sheet reports the following information:

- Your assets: the resources from which it expects to gain some future benefit

- Your liabilities: the debts that it owes to outside individuals or organizations

- Your owner’s equity: your investment in your business

Whereas your income statement tells you how much income you earned over some period of time, your balance sheet tells you what you have (and where it came from) at a specific point in time.

Most companies prepare financial statements on a twelve-month basis—that is, for a fiscal year which ends on December 31 or some other logical date, such as June 30 or September 30. Why do fiscal years vary? A company generally picks a fiscal-year end date that coincides with the end of its peak selling period; thus a crabmeat processor might end its fiscal year in October, when the crab supply has dwindled. Most companies also produce financial statements on a quarterly or monthly basis. For Stress-Buster, you’ll want to prepare a monthly balance sheet.

The Accounting Equation

The balance sheet is based on the accounting equation:

assets = liabilities + owner’s equity

This important equation highlights the fact that a company’s assets came from somewhere: either from loans (liabilities) or from investments made by the owners (owner’s equity). This means that the asset section of the balance sheet on the one hand and the liability and owner’s-equity section on the other must be equal, or balance. Thus the term balance sheet.

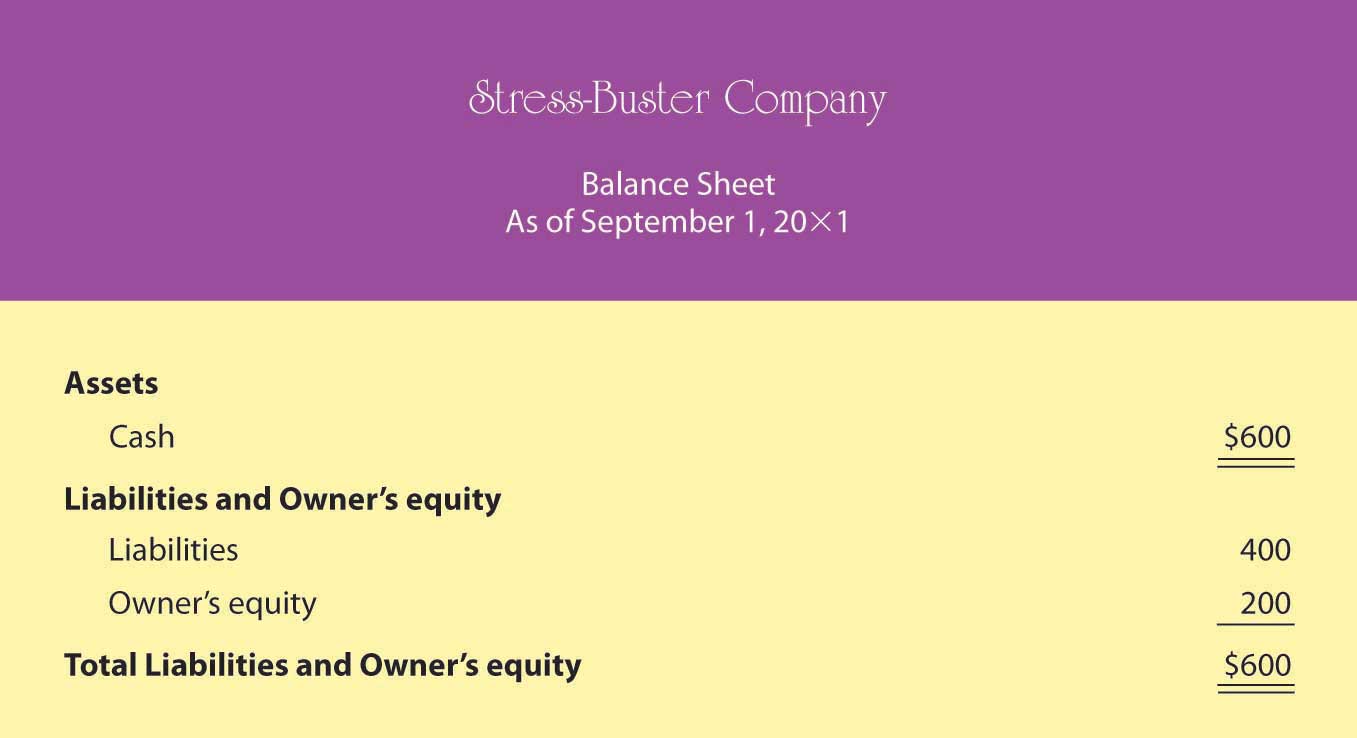

Let’s prepare two balance sheets for your company: one for the first day you started and one for the end of your first month of business. We’ll assume that when you started Stress-Buster, you borrowed $400 from your parents and put in $200 of your own money. If you look at your first balance sheet in Figure 12.9 “Balance Sheet Number One for Stress-Buster Company” you’ll see that your business has $600 in cash (your assets): Of this total, you borrowed $400 (your liabilities) and invested $200 of your own money (your owner’s equity). So far, so good: Your assets section balances with your liabilities and owner’s equity section.

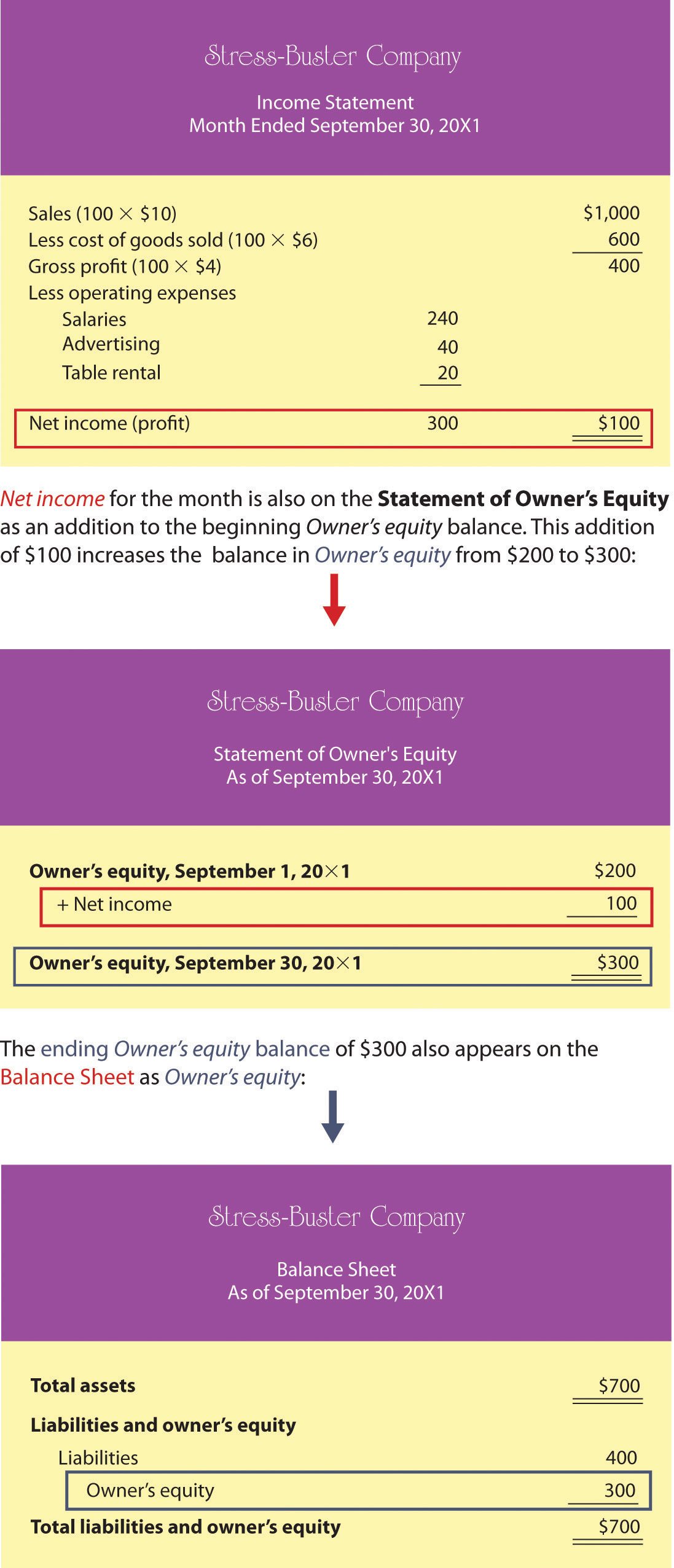

Now let’s see how things have changed by the end of the month. Recall that Stress-Buster earned $100 (based on sales of 100 units) during the month of September and that you decided to leave these earnings in the business. This $100 profit increases two items on your balance sheet: the assets of the company (its cash) and your investment in it (its owner’s equity). Figure 12.10 “Balance Sheet Number Two for Stress-Buster Company” shows what your balance sheet will look like on September 30. Once again, it balances. You now have $700 in cash: $400 that you borrowed plus $300 that you’ve invested in the business (your original $200 investment plus the $100 profit from the first month of operations, which you’ve kept in the business).

The Statement of Owner’s Equity

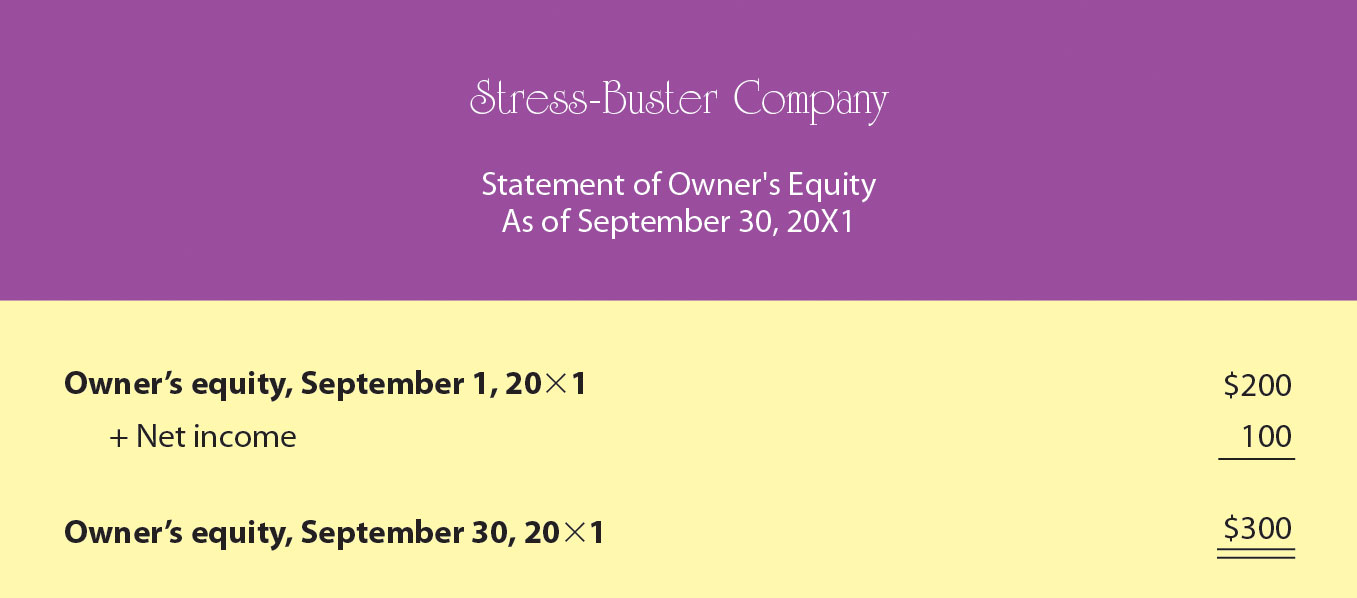

Note that we used the net income figure from your income statement to update the owner’s equity section of your end-of-month balance sheet. Often, companies prepare an additional financial statement, called the statement of owner’s equity, which details changes in owner’s equity for the reporting period. Figure 12.11 “Sample Statement of Owner’s Equity for Stress-Buster Company” shows what this statement looks like.

How Do Financial Statements Relate to One Another?

When you prepare your financial statements, you should complete them in a certain order:

- Income statement

- Statement of owner’s equity

- Balance sheet

Why must they be prepared in this order? Because financial statements are interrelated: Numbers generated on one financial statement appear on other financial statements. Figure 12.12 “How Financial Statements Relate to One Another” presents Stress-Buster’s financial statements for the month ended September 30, 20X1. As you review these statements, note that in two cases, numbers from one statement appear in another statement:

If the interlinking numbers are carried forward correctly, and if assets and liabilities are listed correctly, then the balance sheet will balance: Total assets will equal the total of liabilities plus owner’s equity.

Key Takeaways

- Accountants prepare four financial statements: income statement, statement of owner’s equity, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows (which is discussed later in the chapter).

- The income statement shows a firm’s revenues and expenses and whether it made a profit.

- The balance sheet shows a firm’s assets, liabilities and owner’s equity (the amount that its owners have invested in it).

-

The balance sheet is based on the accounting equation:

assets = liabilities + owner’s equity

This equation highlights the fact that a company’s assets came from one of two sources: either from loans (its liabilities) or from investments made by owners (its owner’s equity).

- The statement of owner’s equity reports the changes in owner’s equity that have occurred over a specified period of time.

- Financial statements should be competed in a certain order: income statement, statement of owner’s equity, and balance sheet. These financial statements are interrelated because numbers generated on one financial statement appear on other financial statements.

- Breakeven analysis is a technique used to determine the level of sales needed to break even—to operate at a sales level at which you have neither profit nor loss.

- To break even, total sales revenue must exactly equal all your expenses (both variable and fixed costs).

- To calculate the breakeven point in units to be sold, you divide fixed costs by contribution margin per unit (selling price per unit minus variable cost per unit).

- This technique can also be used to determine the level of sales needed to obtain a specified profit.

Exercises

-

(AACSB) Analysis

Describe the information provided by each of these financial statements: income statement, balance sheet, statement of owner’s equity. Identify ten business questions that can be answered by using financial accounting information. For each question, indicate which financial statement (or statements) would be most helpful in answering the question, and why.

-

(AACSB) Analysis

You’re the president of a student organization, and to raise funds for a local women’s shelter you want to sell single long-stem red roses to students on Valentine’s Day. Each prewrapped rose will cost $3. An ad for the college newspaper will cost $100, and supplies for posters will cost $60. If you sell the roses for $5, how many roses must you sell to break even? Because breaking even won’t leave you any money to donate to the shelter, you also want to know how many roses you’d have to sell to raise $500. Does this seem like a realistic goal? If the number of roses you need to sell in order to raise $500 is unrealistic, what could you do to reach this goal?

1We’ll discuss the statement of cash flows later in the chapter.