10.5 Forecasting Demand

Learning Objective

- Forecast demand for a product.

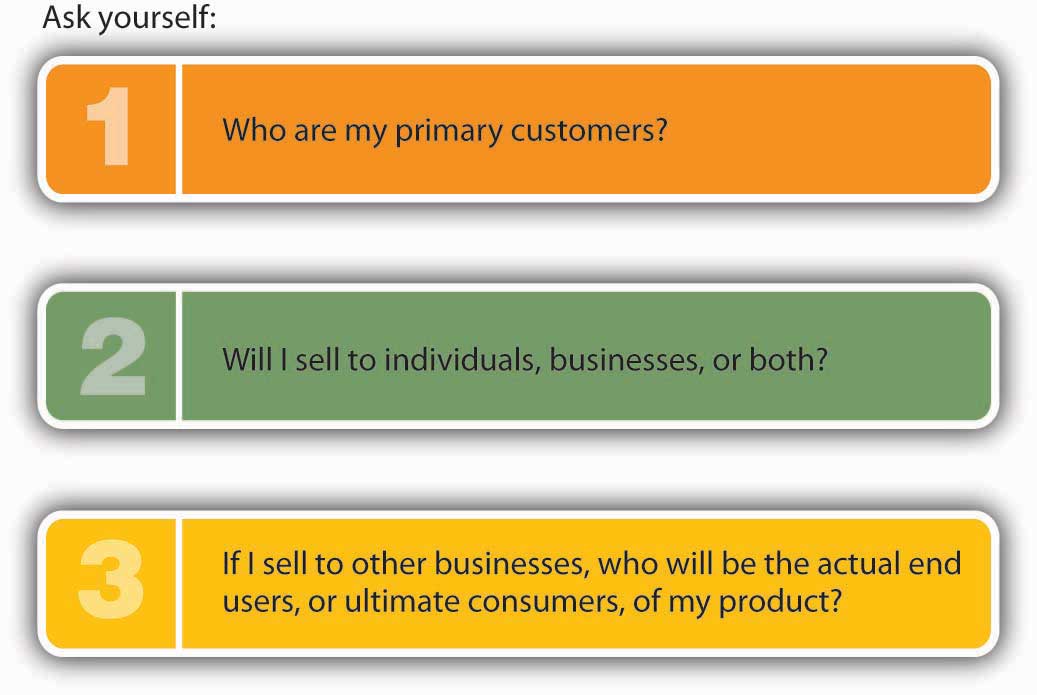

It goes without saying, but we’ll say it anyway: without enough customers, your business will go nowhere. So, before you delve into the complex, expensive world of developing and marketing a new product, ask yourself questions like those in Figure 10.5 “When to Develop and Market a New Product”. When Bob Montgomery asked himself these questions, he concluded that he had two groups of customers for the PowerSki Jetboard: (1) the dealerships that would sell the product and (2) the water-sports enthusiasts who would buy and use it. His job, therefore, was to design a product that dealers would want to sell and enthusiasts would buy. When he was confident that he could satisfy these criteria, he moved forward with his plans to develop the PowerSki Jetboard.

After you’ve identified a group of potential customers, your next step is finding out as much as you can about what they think of your product idea. Remember: because your ultimate goal is to roll out a product that satisfies customer needs, you need to know ahead of time what your potential customers want. Precisely what are their unmet needs? Ask them questions such as these (Ulrich & Eppinger, 2000; Allen, 2001):

- What do you like about this product idea? What don’t you like?

- What improvements would you make?

- What benefits would you get from it?

- Would you buy it? Why, or why not?

- What would it take for you to buy it?

Before making a substantial investment in the development of a product, you need to ask yourself yet another question: are there enough customers willing to buy my product at a price that will allow me to make a profit? Answering this question means performing one of the hardest tasks in business: forecasting demand for your proposed product. There are several possible approaches to this task that can be used alone or in combination.

People in Similar Businesses

Though some businesspeople are reluctant to share proprietary information, such as sales volume, others are willing to help out individuals starting new businesses or launching new products. Talking to people in your prospective industry (or one that’s similar) can be especially helpful if your proposed product is a service. Say, for example, that you plan to open a pizza parlor with a soap opera theme: customers will be able to eat pizza while watching reruns of their favorite soap operas on personal TV/DVD sets. If you visited a few local restaurants and asked owners how many customers they served every day, you’d probably learn enough to estimate the number of pizzas that you’d serve during your first year. If the owners weren’t cooperative, you could just hang out and make an informal count of the customers.

Potential Customers

You can also learn a lot by talking with potential customers. Ask them how often they buy products similar to the one you want to launch. Where do they buy them and in what quantity? What factors affect demand for them? If you were contemplating a frozen yogurt store in Michigan, it wouldn’t hurt to ask customers coming out of a bakery whether they’d buy frozen yogurt in the winter.

Published Industry Data

To get some idea of the total market for products like the one you want to launch, you might begin by examining pertinent industry research. For example, to estimate demand for jogging shoes among consumers sixty-five and older, you could look at data published on the industry association’s Web site, National Sporting Goods Association, http://www.nsga.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=1 (Running USA, 2011; National Sporting Goods Association, 2011). Here you’d find that forty million jogging/running shoes were sold in the United States in 2008 at an average price of $58 per pair. The Web site also reports that the number of athletes who are at least forty and who participate in road events increased by more than 50 percent over a ten year period (USA Track & Field, 2011). To find more specific information—say, the number of joggers older than sixty-five—you could call or e-mail USA Track and Field. You might find this information in an eighty-seven-page statistical study of retail sporting-goods sales published by the National Sporting Goods Association (2011). If you still don’t get a useful answer, try contacting organizations that sell industry data. American Sports Data, for instance, provides demographic information on no fewer than twenty-eight fitness activities, including jogging (American Sports Data, 1987). You’d want to ask them for data on the number of joggers older than sixty-five living in Florida. There’s a lot of valuable and available industry-related information that you can use to estimate demand for your product.

Now, let’s say that your research turns up the fact that there are three million joggers older than sixty-five and that six hundred thousand of them live in Florida, which attracts 20 percent of all people who move when they retire (Zagier, 2003). How do you use this information to estimate the number of jogging shoes that you’ll be able to sell during your first year of business? First, you have to estimate your market share: your portion of total sales in the older-than-sixty-five jogging shoe market in Florida. Being realistic (but having faith in an excellent product), you estimate that you’ll capture 2 percent of the market during your first year. So you do the math: 600,000 pairs of jogging shoes sold in Florida × 0.02 (a 2 percent share of the market) = 12,000, the estimated first-year demand for your proposed product.

Granted, this is just an estimate. But at least it’s an educated guess rather than a wild one. You’ll still want to talk with people in the industry, as well as potential customers, to hear their views on the demand for your product. Only then would you use your sales estimate to make financial projections and decide whether your proposed business is financially feasible. We’ll discuss this process in a later chapter.

Key Takeaways

- After you’ve identified a group of potential customers, your next step is finding out as much as you can about what they think of your product idea.

- Before making a substantial investment in the development of a product, you need to ask yourself: are there enough customers willing to buy my product at a price that will allow me to make a profit?

- Answering this question means performing one of the hardest tasks in business: forecasting demand for your proposed product.

- There are several possible approaches to this task that can be used alone or in combination.

- You can obtain helpful information about product demand by talking with people in similar businesses and potential customers.

- You can also examine published industry data to estimate the total market for products like yours and estimate your market share, or portion of the targeted market.

Exercise

(AACSB) Analysis

Your friends say you make the best pizzas they’ve ever eaten, and they’re constantly encouraging you to set up a pizza business in your city. You have located a small storefront in a busy section of town. It doesn’t have space for an eat-in restaurant, but it will allow customers to pick up their pizzas. You will also deliver pizzas. Before you sign a lease and start the business, you need to estimate the number of pizzas you will sell in your first year. At this point you plan to offer pizza in only one size.

Before arriving at an estimate, answer these questions:

- What factors would you consider in estimating pizza sales?

- What assumptions will you use in estimating sales (for example, the hours your pizza shop will be open)?

- Where would you obtain needed information to calculate an estimate?

Then, estimate the number of pizzas you will sell in your first year of operations.

References

Allen, K., Entrepreneurship for Dummies (Foster, CA: IDG Books, 2001), 79.

American Sports Data, “Trends in U.S. Physical Fitness Behavior (1987–Present),” http://www.americansportsdata.com/phys_fitness_trends1.asp (accessed October 28, 2011).

National Sporting Goods Association, http://nsga.org (accessed October 28, 2011).

National Sporting Goods Association, “Sporting Goods Market in 2010,” National Sporting Goods Association, http://www.nsga.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=1 (accessed October 28, 2011).

Running USA, “Running USA: Running Defies The Great Recession, Running USA’s State of the Sport 2010—Part II,” LetsRun.com, http://www.letsrun.com/2010/recessionproofrunning0617.php (accessed October 28, 2011)

Ulrich, K., and Steven Eppinger, Product Design and Development, 2nd ed. (New York: Irwin McGraw-Hill, 2000), 66

USA Track & Field, “Long Distance Running: State of the Sport,” USA Track & Field, http://www.usatf.org/news/specialReports/2003LDRStateOfTheSport.asp (accessed October 29, 2011).

Zagier, A. S., “Eyeing Competition, Florida Increases Efforts to Lure Retirees,” Boston Globe, December 26, 2003, http://www.boston.com/news/nation/articles/2003/12/26/eyeing_competition_florida_increases_efforts_to_lure_retirees (accessed October 28, 2011).