7.4 What Makes a Great Place to Work?

Learning Objective

- Identify factors that make an organization a good place to work, including competitive compensation and benefits packages.

Every year, the Great Places to Work Institute analyzes comments from thousands of employees and compiles a list of “The 100 Best Companies to Work for in America,” which is published in Fortune magazine. Having compiled its list for more than twenty years, the institute concludes that the defining characteristic of a great company to work for is trust between managers and employees. Employees overwhelmingly say that they want to work at a place where employees “trust the people they work for, have pride in what they do, and enjoy the people they work with” (Great Place to Work Institute, 2011). They report that they’re motivated to perform well because they’re challenged, respected, treated fairly, and appreciated. They take pride in what they do, are made to feel that they make a difference, and are given opportunities for advancement (Great Place to Work Institute, 2006). The most effective motivators, it would seem, are closely aligned with Maslow’s higher-level needs and Herzberg’s motivating factors.

Job Redesign

The average employee spends more than two thousand hours a year at work. If the job is tedious, unpleasant, or otherwise unfulfilling, the employee probably won’t be motivated to perform at a very high level. Many companies practice a policy of job redesign to make jobs more interesting and challenging. Common strategies include job rotation, job enlargement, and job enrichment.

Job Rotation

Specialization promotes efficiency because workers get very good at doing particular tasks. The drawback is the tedium of repeating the same task day in and day out. The practice of job rotation allows employees to rotate from one job to another on a systematic basis, eventually cycling back to their original tasks. A computer maker, for example, might rotate a technician into the sales department to increase the employee’s awareness of customer needs and to give the employee a broader understanding of the company’s goals and operations. A hotel might rotate an accounting clerk to the check-in desk for a few hours each day to add variety to the daily workload. Rotated employees develop new skills and gain experience that increases their value to the company, which benefits management because cross-trained employees can fill in for absentees, thus providing greater flexibility in scheduling.

Job Enlargement

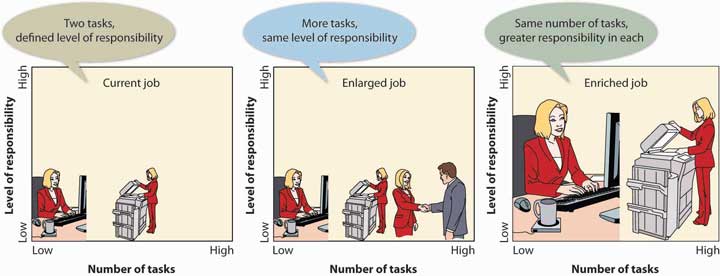

Instead of a job in which you performed just one or two tasks, wouldn’t you prefer a job that gave you many different tasks? In theory, you’d be less bored and more highly motivated if you had a chance at job enlargement—the policy of enhancing a job by adding tasks at similar skill levels (see Figure 7.7 “Job Enlargement versus Job Enrichment”). The job of sales clerk, for example, might be expanded to include gift-wrapping and packaging items for shipment. The additional duties would add variety without entailing higher skill levels.

Job Enrichment

As you can see from Figure 7.7 “Job Enlargement versus Job Enrichment”, merely expanding a job by adding similar tasks won’t necessarily “enrich” it by making it more challenging and rewarding. Job enrichment is the practice of adding tasks that increase both responsibility and opportunity for growth. It provides the kinds of benefits that, according to Maslow and Herzberg, contribute to job satisfaction: stimulating work, sense of personal achievement, self-esteem, recognition, and a chance to reach your potential.

Consider, for example, the evolving role of support staff in the contemporary office. Today, employees who used to be called “secretaries” assume many duties previously in the domain of management, such as project coordination and public relations. Information technology has enriched their jobs because they can now apply such skills as word processing, desktop publishing, creating spreadsheets, and managing databases. That’s why we now hear such a term as administrative assistant instead of secretary (Kerka, 2011).

Work/Life Quality

Building a career requires a substantial commitment in time and energy, and most people find that they aren’t left with much time for nonwork activities. Fortunately, many organizations recognize the need to help employees strike a balance between their work and home lives (Greenhaus, et. al., 2003). By helping employees combine satisfying careers and fulfilling personal lives, companies tend to end up with a happier, less-stressed, and more productive workforce. The financial benefits include lower absenteeism, turnover, and health care costs.

Alternative Work Arrangements

The accounting firm KPMG, which has made the list of the “100 Best Companies for Working Mothers” for twelve years (KPMG firm, 2011), is committed to promoting a balance between its employees’ work and personal lives. KPMG offers a variety of work arrangements designed to accommodate different employee needs and provide scheduling flexibility (KPMG, 2011).

Flextime

Employers who provide for flextime set guidelines that allow employees to designate starting and quitting times. Guidelines, for example, might specify that all employees must work eight hours a day (with an hour for lunch) and that four of those hours must be between 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. Thus, you could come in at 7 a.m. and leave at 4 p.m., while coworkers arrive at 10 a.m. and leave at 7 p.m. With permission you could even choose to work from 8 a.m to 2 p.m., take two hours for lunch, and then work from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m.

Compressed Workweeks

Rather than work eight hours a day for five days a week, you might elect to earn a three-day weekend by working ten hours a day for four days a week.

Part-Time Work

If you’re willing to have your pay and benefits adjusted accordingly you can work fewer than forty hours a week.

Job Sharing

Under job sharing, two people share one full-time position, splitting the salary and benefits of the position as each handles half the job. Often they arrange their schedules to include at least an hour of shared time during which they can communicate about the job.

Telecommuting

Telecommuting means that you regularly work from home (or from some other nonwork location). You’re connected to the office by computer, fax, and phone. You save on commuting time, enjoy more flexible work hours, and have more opportunity to spend time with your family. A study of 5,500 IBM employees (one-fifth of whom telecommute) found that those who worked at home not only had a better balance between work and home life but also were more highly motivated and less likely to leave the organization (Reported in Work-Life, 2011) (The Business Case for Telecommuting, 2011).

Though it’s hard to count telecommuters accurately, some estimates put the number of people who work at home at least one day a week at 20 percent. This estimate includes 2 percent of workers who run home-based businesses and 2 percent who work exclusively at home for other companies (Telework Research Network, 2011). Telecommuting isn’t for everyone. Working at home means that you have to discipline yourself to avoid distractions, such as TV, personal phone calls, home chores, or pets, and some people feel isolated from social interaction in the workplace.

Family-Friendly Programs

In addition to alternative work arrangements, many employers, including KPMG, offer programs and benefits designed to help employees meet family and home obligations while maintaining busy careers. KPMG offers each of the following benefits (KPMG, 2011).

Dependent Care

Caring for dependents—young children and elderly parents—is of utmost importance to some employees, but combining dependent-care responsibilities with a busy job can be particularly difficult. KPMG provides on-site child care during tax season (when employees are especially busy) and offers emergency backup dependent care all year round, either at a provider’s facility or in the employee’s home. To get referrals or information, employees can call KPMG’s LifeWorks Resource and Referral Service. KPMG is by no means unique in this respect: more than eight thousand companies maintain on-site day care (Harris, 2000) and 18 percent of all U.S. companies offer child-care resources or referral services (CNNMoney, 2003).

Paid Parental Leave

Any employee (whether male or female) who becomes a parent can take two weeks of paid leave. New mothers also get time off through short-term disability benefits.

Caring for Yourself

Like many companies, KPMG allows employees to aggregate all paid days off and use them in any way they want. In other words, instead of getting, say, ten sick days, five personal days, and fifteen vacation days, you get a total of thirty days to use for anything. If you’re having personal problems, you can contact the Employee Assistance Program. If staying fit makes you happier and more productive, you can take out a discount membership at one of more than nine thousand health clubs.

Unmarried without Children

You’ve undoubtedly noticed by now that many programs for balancing work and personal lives target married people, particularly those with children. Single individuals also have trouble striking a satisfactory balance between work and nonwork activities, but many single workers feel that they aren’t getting equal consideration from employers (Collins & Hoover, 1995). They report that they’re often expected to work longer hours, travel more, and take on difficult assignments to compensate for married employees with family commitments.

Needless to say, requiring singles to take on additional responsibilities can make it harder for them to balance their work and personal lives. It’s harder to plan and keep personal commitments while meeting heavy work responsibilities, and establishing and maintaining social relations is difficult if work schedules are unpredictable or too demanding. Frustration can lead to increased stress and job dissatisfaction. In several studies of stress in the accounting profession, unmarried workers reported higher levels of stress than any other group, including married people with children1.

With singles, as with married people, companies can reap substantial benefits from programs that help employees balance their work and nonwork lives: they can increase job satisfaction and employee productivity and reduce turnover. PepsiCo, for example, offers a “concierge service,” which maintains a dry cleaner, travel agency, convenience store, and fitness center on the premises of its national office in Somers, New York (Lifestyle Concierge Services, 2011). Single employees seem to find these services helpful, but what they value most of all is control over their time. In particular, they want predictable schedules that allow them to plan social and personal activities. They don’t want employers assuming that being single means that they can change plans at the last minute. It’s often more difficult for singles to deal with last-minute changes because, unlike married coworkers, they don’t have the at-home support structure to handle such tasks as tending to elderly parents or caring for pets.

Compensation and Benefits

Though paychecks and benefits packages aren’t the only reasons why people work, they do matter. Competitive pay and benefits also help organizations attract and retain qualified employees. Companies that pay their employees more than their competitors generally have lower turnover. Consider, for example, The Container Store, which regularly appears on Fortune magazine’s list of “The 100 Best Companies to Work For” (Fortune, 2011). The retail chain staffs its stores with fewer employees than its competitors but pays them more—in some cases, three times the industry average for retail workers. This strategy allows the company to attract extremely talented workers who, moreover, aren’t likely to leave the company. Low turnover is particularly valuable in the retail industry because it depends on service-oriented personnel to generate repeat business.

In addition to salary and wages, compensation packages often include other financial incentives, such as bonuses and profit-sharing plans, as well as benefits, such as medical insurance, vacation time, sick leave, and retirement accounts.

Wages and Salaries

The largest, and most important, component of a compensation package is the payment of wages or salary. If you’re paid according to the number of hours you work, you’re earning wages. Counter personnel at McDonald’s, for instance, get wages, which are determined by multiplying an employee’s hourly wage rate by the number of hours worked during the pay period. On the other hand, if you’re paid for fulfilling the responsibilities of a position—regardless of the number of hours required to do it—you’re earning a salary. The McDonald’s manager gets a salary for overseeing the operations of the restaurant. He or she is expected to work as long as it takes to get the job done, without any adjustment in compensation.

Piecework and Commissions

Sometimes it makes more sense to pay workers according to the quantity of product that they produce or sell. Byrd’s Seafood, a crab-processing plant in Crisfield, Maryland, pays workers on piecework: Workers’ pay is based on the amount of crabmeat that’s picked from recently cooked crabs. (A good picker can produce fifteen pounds of crabmeat an hour and earn about $100 a day.) (Crisfield Off the Beaten Path, 2006; Learner, 2000). If you’re working on commission, you’re probably getting paid for quantity of sales. If you were a sales representative for an insurance company, like The Hartford, you’d get a certain amount of money for each automobile or homeowner policy that you sell (The Hartford, 2011).

Incentive Programs

In addition to regular paychecks, many people receive financial rewards based on performance, whether their own, their employer’s, or both. At computer-chip maker Texas Instruments (TI), for example, employees may be eligible for bonuses, profit sharing, and stock options. All three plans are incentive programs: programs designed to reward employees for good performance (Texas Instruments, 2011).

Bonus Plans

TI’s year-end bonuses—annual income given in addition to salary—are based on company-wide performance. If the company has a profitable year, and if you contributed to that success, you’ll get a bonus. If the company doesn’t do well, you’re out of luck, regardless of what you contributed.

Bonus plans have become quite common, and the range of employees eligible for bonuses has widened in recent years. In the past, bonus plans were usually reserved for managers above a certain level. Today, however, companies have realized the value of extending plans to include employees at virtually every level. The magnitude of bonuses still favors those at the top. High-ranking officers (such as CEOs and CFOs) often get bonuses ranging from 30 percent to 50 percent of their salaries. Upper-level managers may get from 15 percent to 25 percent and middle managers from 10 percent to 15 percent. At lower levels, employees may expect bonuses from 3 percent to 5 percent of their annual compensation (Opdyke, 2004).

Profit-Sharing Plans

TI also maintains a profit-sharing plan, which relies on a predetermined formula to distribute a share of the company’s profits to eligible employees. Today, about 40 percent of all U.S. companies offer some type of profit-sharing program (Obringer, 2011). TI’s plan, however, is a little unusual: while most plans don’t allow employees to access profit-sharing funds until retirement or termination, TI employees get their shares immediately—in cash.

TI’s plan is also pretty generous—as long as the company has a good year. Here’s how it works. An employee’s profit share depends on the company’s operating profit for the year. If profits from operations reach 10 percent of sales, the employee gets a bonus worth 4 percent of his or her salary. If operating profit soars to 20 percent, the employee bonuses go up to 26 percent of salary. But if operating profits fall short of a certain threshold, nobody gets anything (Texas Instruments, 2011).

Stock-Option Plans

Like most stock-option plans, the TI plan gives employees the right to buy a specific number of shares of company stock at a set price on a specified date. At TI, an employee may buy stock at its selling price at the time when he or she was given the option. So, if the price of the stock goes up, the employee benefits. Say, for example, that the stock was selling for $30 a share when the option was granted in 2007. In 2011, it was selling for $40 a share. Exercising his or her option, the employee could buy TI stock at the 2007 price of $30 a share—a bargain price (Texas Instruments, 2011).

At TI, stock options are used as an incentive to attract and retain top people. Starbucks, by contrast, isn’t nearly as selective in awarding stock options. At Starbucks, all employees can earn “Bean Stock”—the Starbucks employee stock-option plan. Both full- and part-time employees get options to buy Starbucks shares at a set price. If the company does well and its stock goes up, employees make a profit. CEO Howard Schultz believes that Bean Stock pays off: because employees are rewarded when the company does well, they have a stronger incentive to add value to the company (and so drive up its stock price). Shortly after the program was begun, the phrase “bean-stocking” became workplace lingo for figuring out how to save the company money.

Benefits

Another major component of an employee’s compensation package is benefits—compensation other than salaries, hourly wages, or financial incentives. Types of benefits include the following:

- Legally required benefits (Social Security and Medicare, unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation)

- Paid time off (vacations, holidays, sick leave)

- Insurance (health benefits, life insurance, disability insurance)

- Retirement benefits

Unfortunately, the cost of providing benefits is staggering. According to the Employee Benefit Research Institute, it costs an employer 30 percent of a worker’s salary to provide the same worker with benefits. If you include pay for time not worked (while on vacation or sick and so on), the percentage increases to 41 percent. So if you’re a manager making $100,000 a year, your employer is also paying out another $41,000 for your benefits. The most money goes for health care (8 percent of salary costs), paid time off (11 percent), and retirement benefits (5 percent) (Employee Benefit Reasearch Institute, 2011).

Some workers receive only benefits required by law, including Social Security, unemployment, and workers’ compensation. Low-wage workers generally get only limited benefits and part-timers often nothing at all (National Compensation Survey, 2003). Again, Starbucks is generous in offering benefits. The company provides benefits even to the part-timers who make up two-thirds of the company’s workforce; anyone working at least twenty hours a week gets medical coverage.

Key Takeaways

- Employees report that they’re motivated to perform well when they’re challenged, respected, treated fairly, and appreciated.

-

Other factors may contribute to employee satisfaction. Some companies use job redesign to make jobs more interesting and challenging.

- Job rotation allows employees to rotate from one job to another on a systematic basis.

- Job enlargement enhances a job by adding tasks at similar skill levels.

- Job enrichment adds tasks that increase both responsibility and opportunity for growth.

- Many organizations recognize the need to help employees strike a balance between their work and home lives and offer a variety of work arrangements to accommodate different employee needs.

- Flextime allows employees to designate starting and quitting times, compress workweeks, or perform part-time work.

- With job sharing, two people share one full-time position.

- Telecommuting means working from home. Many employers also offer dependent care, paid leave for new parents, employee-assistance programs, and on-site fitness centers.

- Competitive compensation also helps.

- Workers who are paid by the hour earn wages, while those who are paid to fulfill the responsibilities of the job earn salaries.

- Some people receive commissions based on sales or are paid for output, based on a piecework approach.

- In addition to pay, many employees can earn financial rewards based on their own and/or their employer’s performance.

- They may receive year-end bonuses, participate in profit-sharing plans (which use predetermined formulas to distribute a share of company profits among employees), or receive stock options (which let them buy shares of company stock at set prices).

- Another component of many compensation packages is benefits—compensation other than salaries, wages, or financial incentives. Benefits may include paid time off, insurance, and retirement benefits.

Exercise

(AACSB) Analysis

- Describe the ideal job that you’d like to have once you’ve finished college. Be sure to explain the type of work schedule that you’d find most satisfactory, and why. Identify family-friendly programs that you’d find desirable and explain why these appeal to you.

- Describe a typical compensation package for a sales manager in a large organization. If you could design your own compensation package, what would it include?

1Data was obtained from 1988 and 1991 studies of stress in public accounting by Karen Collins and from a 1995 study on quality of life in the accounting profession by Collins and Jeffrey Greenhaus. Analysis of the data on single individuals was not separately published.

References

The Business Case for Telecommuting, Reported in Work-Life and Human Capital Solutions, The Business Case for Telecommuting (Minnetonka, MN: WFC Resources), http://worklifeexpo.com/EXPO/docs/The_Business_Case_for_Telecommuting-WFCResources.pdf, (accessed October 10, 2011).

CNNMoney, “New List of Best Companies for Mom,” CNNMoney, September 23, 2003 http://money.cnn.com/2003/09/23/news/companies/working_mother/?cnn=yes (accessed October 11, 2011).

Collins, K., and Elizabeth Hoover, “Addressing the Needs of the Single Person in Public Accounting,” Pennsylvania CPA Journal, June 1995, 16.

Crisfield Off the Beaten Path, “Crab Pickers,” Crisfield Off the Beaten Path, http://www.crisfield.com/sidestreet/ickers.html (accessed May 6, 2006).

Employee Benefit Reasearch Institute, “FAQs About Benefits—General Overview,” Employee Benefit Research Institute, http://www.ebri.org/publications/benfaq/?fa=fullfaq (accessed October 10, 2011).

Fortune, “The 100 Best Companies to Work For,” Fortune, http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/bestcompanies/2011/index.html (accessed October 10, 2011).

Great Place to Work Institute, “What do Employees Say?” Great Place to Work Institute, http://www.greatplacetowork.com/great/employees.php (accessed May 6, 2006).

Great Place to Work Institute, “What Is a Great Workplace?,” Great Place to Work Institute, http://www.greatplacetowork.com/our-approach/what-is-a-great-workplace (accessed October 10, 2011).

Greenhaus, J., Karen Collins, and Jason Shaw, “The Relationship between Work-Family Balance and Quality of Life,” Journal of Vocational Behavior 63, 2003, 510–31.

Harris, B., “Child Care Comes to Work,” Los Angeles Times, November 19, 2000, http://articles.latimes.com/2000/nov/19/news/wp-54138, (accessed October 11, 2011).

The Hartford, “Benefits,” The Hartford, http://thehartford.com/utility/careers/career-benefits (accessed October 11, 2011).

Kerka, S., “The Changing Role of Support Staff,” http://calpro-online.com/eric/docgen.asp?tbl=archive&ID=A019 (accessed October 10, 2011).

KPMG firm Web site, Careers Section, http://www.kpmgcareers.com/whoweare/awards.shtml (accessed October 11, 2011).

KPMG, “Career,” KPMG, http://www.kpmgcareers.com/index.shtml (accessed October 10, 2011).

Learner, N., “Ashore, A Way of Life Built around the Crab,” Christian Science Monitor, June 26, 2000, http://csmonitor.com/cgi-bin/durableRedirect.pl?/durable/2000/06/26/fp15s1-csm.shtml (accessed May 6, 2006).

Lifestyle Concierge Services, “Concierge Service Is A Surprisingly Low Cost Solution That Can Meet A Variety Of Needs With A Single Provider,” Lifestyle Concierge Services, http://www.lifestyleconciergeservices.com/Corporate-Concierge-Service-for-businesses.html (accessed October 11, 2011).

National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in Private Industry, 2003, U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 2003, 2, http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/home.htm (accessed October 9, 2011).

Obringer, L. A., “How Employee Compensation Works—Stock Options/Profit Sharing,” HowStuffWorks, http://money.howstuffworks.com/benefits.htm (accessed October 11, 2011).

Opdyke, J. D., “Getting a Bonus Instead of a Raise,” Wall Street Journal, December 29, 2004, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB110427526449111461.html, (accessed October 7, 2011).

Telework Research Network, “How Many People Telecommute?,” Telework Research Network, http://www.teleworkresearchnetwork.com/research/people-telecommute (accessed October 11, 2011).

Texas Instruments, “Benefits,” http://www.ti.com/recruit/docs/benefits.shtml (accessed October 11, 2011).