Chapter 6: Intimate Partner Violence among Immigrants and Refugees

Jaime Ballard (Family Social Science, University of Minnesota), Matthew Witham (Family Social Science, University of Minnesota), and Dr. Mona Mittal (School of Public Health, University of Maryland)

Introduction

Imagine that you, your partner, and your children are recently arrived in the United States. You do not speak the language well, and everything from the foods in grocery stores to the type of floor in your apartment feels new to you. While you and your family try to adjust to these changes, what kind of stresses would you be under? How would it affect your relationship with your partner?

Now imagine that in the midst of these stressors and changes, your partner periodically comes home and snaps. Your partner curses at you, grabs your shoulders, and throws you down on the ground. What do you do? Who in this new country can help you?

Approximately one out of every three women (36%) and one out of every four men (29%) in the United States report lifetime experiences of rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner (Black et al., 2011). Rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) are even higher among immigrants, ranging from 30% to 60% (Biafora & Warbeit, 2007; Erez, Adelman, & Gregory, 2009; Hazen & Soriano, 2005; Sabina, Cuevas, & Zadnik, 2014). There are likely additional incidents that go unreported when immigrant and refugee groups do not know how to access or navigate social and legal services in the United States, or when immigrants and refugees come from nations where violence against women is culturally accepted.

IPV has a significant impact on immigrant and refugee women and their families. Immigrant and refugee women who experience IPV are more likely to experience mental health issues and distress; for example, Latina immigrants who experience IPV are three times as likely to be diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as Latina immigrants with no experiences of IPV (Fedovskiy, Higgins, & Paranjape, 2008). Also, children who witness IPV are more likely to experience anxiety, depression, PTSD, and aggression than children with no exposure to IPV (Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, 2003; Wolfe, Crooks, Lee, & McIntyre-Smith, 2003). IPV can also be fatal. Studies show that immigrant women are more likely than United States-born women to die from IPV (Frye, Hosein, Waltermaurer, Blaney, & Wilt, 2005). IPV is particularly threatening for undocumented immigrants as their access to police and social services is limited and accusations of abuse in the presence of a child can lead to both deportation and alternative custody arrangements (Rogerson, 2012).

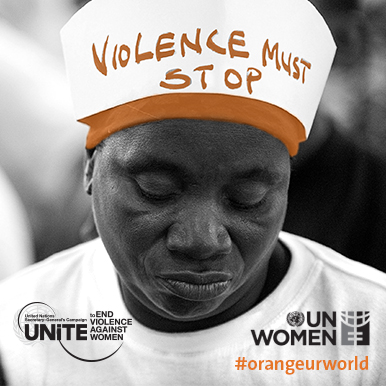

The UN has a campaign to end violence against women across the globe. For 2 weeks in 2013, activists and celebrities wore orange to raise awareness of violence against women.

UN Women – Orange Your World in 16 days – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide a broad overview of IPV and its unique characteristics among immigrants. We will explore IPV-related risk and protective factors, and also discuss how survivors cope with IPV. Finally, we will suggest how future research and interventions might address IPV among immigrants and refugees.

Which term to use?

There is controversy over whether to call people who have experience IPV “victims” or “survivors.” In this chapter we use the word “survivor,” but there are good reasons to use both terms. To read a brief description of the reasons for using each term, visit: https://www.rainn.org/articles/key-terms-and-phrases.