1.2 Current Immigration Policy

Current Immigration Policy

Although the decision to migrate is generally made and motivated by families, immigration policy generally focuses on the individual. For example, visas are granted to individuals, not families. In this section, we will describe the immigration policies that are most influential for today’s families. For an overview of all immigration policies and their historical context, please see Appendices 1-4 (The History of Documented Immigration Policy 1850s-1920s, 1920s-1950s, 1950s to Present, and the History of Undocumented Immigration Policy, respectively).

In the landmark decision of Arizona et al. v. United States (2012), Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy remarked that “The history of the United States is in part made of the stories, talents, and lasting contributions of those who crossed oceans and deserts to come here.”

1952 McCarran-Walter Act: This act and its amendments remains the basic body of immigration law. It opened immigration to all countries, establishing quotas for each (US English Foundation, 2016). This act instituted a priority system for admitting family members of current citizens. Admission preference was given to spouses, children, and parents of U.S. citizens, as well as to skilled workers (Immigration History, 2019). This meant that more families from more countries had the opportunity to reunite in the United States.

1965 Hart-Celler Immigration Act or Immigration and Nationality Act and 1978 Amendments. In this act, the national ethnicity quotas were repealed. Instead, a cap was set for each hemisphere. Once again, priority was given to family reunification and employment skills. This act also expanded the original four admission preferences to seven, adding: (5) siblings of United States citizens; (6) workers, skilled and unskilled, in occupations for which labor was in short supply in the United States; and (7) refugees from Communist-dominated countries or those affected by natural disasters. This expanded the opportunities for family members to reunite in the United States.

1990 Immigration Act. This act eased the limits on family-based immigration (US English Foundation, 2016). It ultimately led to a 40% increase in total admissions (Fix & Passel, 1994).

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. The Dream Act, first introduced in 2001, would allow for conditional permanent residency to immigrants who arrived in the United States as minors and have long-standing United States residency. While this bill has not yet been signed into law, the Obama administration created renewable two-year work permits for those who meet these standards. This had the largest impact on undocumented families. Many children travel to the United States without documents to be with their families, and then spend most of their lives in the United States. If the bill passed, these children would have new opportunities to pursue higher education and jobs in the land they think of as home, without fear of deportation. In 2017, the Trump administration attempted to rescind the DACA memorandum, but federal judges blocked the termination. Individuals with DACA can continue to renew their benefits, but first-time applicants are no longer accepted (American Immigration Council, 2019).

2000 Life Act and Section 245(i). This allowed undocumented immigrants present in the United Sttes to adjust their status to permanent resident, if they had family or employers to sponsor them (US English Foundation, 2016).

2001 Patriot Act: The sociopolitical climate after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks drastically changed immigrant policies in the United States. This act created Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Citizenship and Immigration Services (CIS), greatly enhancing immigration enforcement.

2005 Bill. The House of Representatives passed a bill that increased enforcement at the borders, focusing on national security rather than family or economic influences (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou & Fix, 2006).

2006 Bill. The Senate passed a bill that expanded legal immigration, in order to decrease undocumented immigration (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou & Fix, 2006).

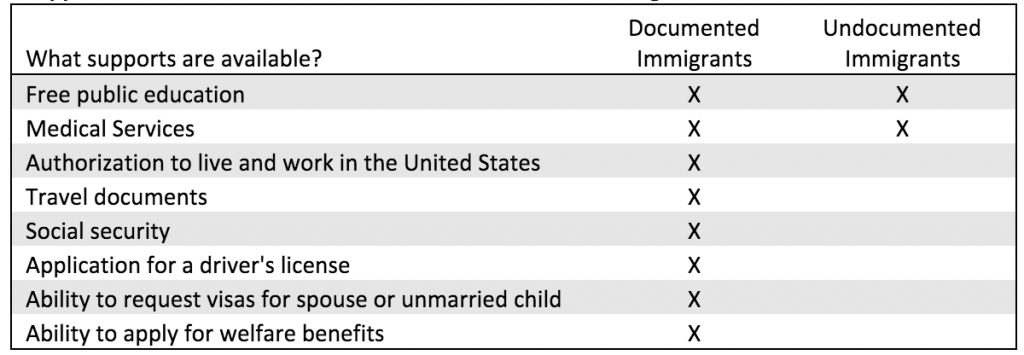

As these policies indicate, it is currently very difficult to enter the United States without documentation. There are few supports available to those who do make it across the border (see Table 1). However, the 2000 Life Act and the Dream Act provide some provisions for families who live in the United States to obtain documentation to remain together, at least temporarily.

For families who want to immigrate with documentation, current policy prioritizes family reunification. Visas are available for family members of current permanent residents, and there are no quotas on family reunification visas (See Textbox 2, “Process for Becoming a Citizen). Even when family members of a current permanent resident are granted a visa, they are a long way from residency. They must wait for their priority date and process extensive paperwork. If a family wants to immigrate to the United States but does not have a family member who is a current permanent resident or a sponsoring employer, options for documented immigration are very limited.

Table 1

Supports available to documented and undocumented immigrants</strong

Textbox 2

Process of Becoming a Citizen, also called “Naturalization”

File a petition for an immigrant visa. The first step of documented immigration is obtaining an immigrant visa. There are a number of ways this can occur:

- For family members. A citizen or lawful permanent resident in the United States can file an immigrant visa petition for their immediate family members in other countries. In some cases, they can file a petition for a fiancé or adopted child.

- For sponsored employees. United States employers sometimes recruit skilled workers who will be hired for permanent jobs. These employers can file a visa petition for the workers.

- For immigrants from countries with low rates of immigration. The Diversity Visa Lottery program accepts applications from individuals in countries with low rates of immigration. These individuals can file an application, and visas are awarded based on random selection.

If prospective immigrants do not fall into one of these categories, their avenues for documented immigration are quite limited. For prospective immigrants who fall within one of these categories, their petition must be approved by USCIS and consular officers. However, they are still a long way from residency.

Wait for priority date. There is an annual limit to the number of available visas in most categories. Petitions are filed chronologically, and each prospective immigrant is given a “priority date.” The prospective immigrant must then wait until there is an available visa, based on their priority date.

Process paperwork. While waiting for the priority date, prospective immigrants can begin to process the paperwork. They must pay processing fees, submit a visa application form, and compile extensive additional documentation (such as evidence of income, proof of relationship, proof of United States status, birth certificates, military records, etc.) They must then complete an interview at the United States. Embassy or Consulate and complete a medical exam. Once all of these steps are complete, the prospective immigrant received an immigrant visa. They can travel to the United States with a green card and enter as a lawful permanent resident (US Visas, n.d.).

A lawful permanent resident is entitled to many of the supports of legal residents, including free public education, authorization to work in the United States, and travel documents to leave and return to the United States (Refugee Council USA, 2019). However, permanent resident aliens remain citizens of their home country, must maintain residence in the United States in order to maintain their status, must renew their status every 10 years, and cannot vote in federal elections (USCIS, 2015).

Apply for citizenship. Generally, immigrants are eligible to apply for citizenship when they have been a permanent resident for at least five years, or three years if they are married to a citizen. Prospective citizens must complete an application, be fingerprinted and have a background check, complete an interview with a USCIS officer, and take an English and civics test. They must then take an Oath of Allegiance (USCIS, 2012).