Enteric System: Pre-Weaning Pigs

Rotaviruses

Clinical importance

Rotaviruses are ubiquitous, and can infect a number of species including avian, swine and human. So far the zoonotic potential of the rotavirus strains infecting pigs has not been proven but rotaviruses issued from the reassortment of swine and human strains are closely monitored. Rotaviruses are an extremely common cause of diarrhea in young suckling piglets, usually within the first 2 weeks of life. Rotaviruses are hardy and can survive in a variety of environmental conditions (up to 9 months in fecal matter at 64F-20C).

Etiology and Transmission

Rotaviruses are non-enveloped RNA viruses. Eight distinct serogroups (A-H) of rotaviruses have been identified in swine. Serogroup A is by far the most prevalent in the swine industry but co-infections with other groups are common. They are widespread, with some countries reporting near 100% seropositivity in adults. Most adult pigs develop immunity and therefore, rarely show clinical signs but they can become silent carriers and shed the virus in the environment. Gilt litters are more at risk, especially if the gilt has not been correctly exposed to the virus before her first farrowing. Indeed, the colostrum concentration in antibodies is low and the piglets poorly protected.

Viruses are transmitted via the fecal-oral route. Indeed, rotaviruses replicate in epithelial cells of both the jejunum and ileum, usually in the villi. Cell death and vili atrophy ensue resulting in diarrhea by malabsorption. The viruses are then shed in the feces. The short incubation period (24-48 hours) means that piglets can express clinical signs within their first week of life.

Associated symptoms

Diarrhea in suckling piglets, before weaning, is the most common symptom. In mild cases, the symptoms disappear within a few days. Maternal immunity is usually sufficient to provide protection against clinical Uncomplicated rotavirus infection results in a yellowish diarrhea with limited (up to 15%) mortality.In more severe cases, secondary infection by E. coli or Isospora suis can cause more severe clinical signs, dehydration, and higher mortality. Adults do not usually express clinical signs.

Which population is more at risk of developing clinical rotavirus infection?

- Nursery pigs

- Suckling piglets from a gilt

- Suckling piglets from a parity 5 sow

Associated lesions

Macroscopic lesions

The main macroscopic lesion seen as a result of rotavirus infection is thin-walled intestine. Jejunum and ileum are filled with a yellowish liquid content. Mesenteric lymph nodes can be enlarged.

Microscopic lesions

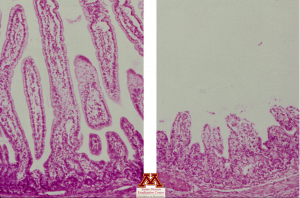

Microscopically the main lesion is villi atrophy as a result of virus replication. The virus specifically attacks differentiated epithelial cells responsible for absorption in the intestine.

Vili atrophy due to rotavirus | Source: Dr. Carlos Pijoan

Diagnosis

The samples to submit for rotavirus diagnosis are feces, intestinal tissue and content of a non-treated acutely infected pig. RT-PCR on those samples gives a quick results and is the most widely-used test. Genotyping of the isolated strain is also available to track the evolution of the virus. Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry can both be used to test epithelial cells for viral presence. Finally, ELISA tests are available to test for antigens but the results are of little interest since the viruses are ubiquitous.

Differential Diagnosis

Rotavirus is one of the main forms of neonatal diarrhea including colibacillosis, clostridia infections, coronaviruses such as TGE and PED – both of which cause higher mortality rates and vomiting-, and coccidiosis – which targets piglets after their second week of life-.

What are the clinical signs associated with a rotavirus infection?

- Yellowish diarrhea and thin-walled intestines

- Diarrhea, vomiting, and high mortality rate

- Hemorrhagic diarrhea and high mortality rate

Treatment, Prevention and Control

There is no treatment available against rotavirus infection. Limiting the impact of the clinical signs, particularly dehydration, by giving the piglets water and electrolytes is one of the most effective options. Additionally, ensuring that piglets do not get chilled by making sure that they stay dry is helpful to limit the mortality rate.

Prevention and control rely on the intake of an appropriate amount of good colostrum to provide piglets with a sufficient amount of antibodies. Commercial vaccines for the sows are available and are usually administered 3 to 4 weeks before farrowing. However, they only include serogroup A for now. In clinical cases, the feedback technique is applied. Farm workers collect fecal matter and intestinal content from affected piglets, dilute it with saline and feed it to the dam in order to expose them to the farm viral strains. Sows then develop immunity and pass it to the piglets through the colostrum. This technique is very effective but must be combined with a thorough cleaning and disinfection of the farrowing rooms to decrease the viral load in the environment. Remember, the virus is non-enveloped and can survive for a long time in fecal matter. Lastly, gilts need to be acclimated appropriately and exposed to the virus before their first farrowing. Eradication is near impossible due to the high prevalence of the virus in US herds and the survival of the virus in the environment.

What is the best way to treat piglets during a rotavirus outbreak?

- Treat the litter with an antibiotic such as gentamicin

- Keep the piglets warm, dry and hydrated

- Move the piglets to another litter so that they can get better colostrum (cross-fostering)