Respiratory System

Pasteurella multocida

Clinical importance

Pasteurella multocida is one of the leading causes of pneumonia in growing pigs. It has a large economic impact as it results in decreased growth rate and feed efficiency as well as increases in premature death and condemnations at slaughter. This disease is ubiquitous, present world-wide and is usually seen in association with other infectious agents.

Etiology and transmission

P.multocida is one of four Pasteurella species, but the only one that routinely infects pigs. There are 5 serotypes and type A is the one that is isolated from pneumonia lesions. P.multocida can be isolated from the nasal cavity and tonsils of healthy animals, therefore it is present in almost every commercial swine herd, even if it is not causing disease. It spreads via nose to nose contact as well as vertical transmission from sow to piglet. It is a secondary respiratory pathogen, meaning that it only causes disease when the mucociliary apparatus becomes damaged due to another pathogen (typically Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, influenza, or PRRS). This allows the bacteria to migrate down the respiratory system and colonize the alveoli.

Associated symptoms

Clinical signs are consistent with other diseases causing pneumonia. Growing and finishing pigs are the most susceptible to pneumonia induced by P.multocida. Coughing, sneezing, and abdominal breathing also called “thumping” is seen in infected pigs. The pigs may appear depressed or less inclined to move. Sudden death is less common in pasteurellosis than with other infections but pigs lose a lot of weight and appear emaciated.

Pneumonia associated with P.multocida infection will disappear if primary respiratory pathogens are under control. True or False?

- True

- False

Associated lesions

Macroscopic lesions

Macroscopic lesions vary depending on the nature of other infectious agents. Consolidation of the cranio-ventral lobes is consistently seen, and more severe than in the case of M.hyopneumoniae infections. Fibrin and adhesions between the lung and the pleura are common. Since P.multocida becomes systemic, pericarditis can also be seen. Lymph nodes near the affected areas are enlarged.

Microscopic lesions

The alveoli present a large number of neutrophils, fibrin, and bacteria typical of a suppurative bronchopneumonia.

Diagnosis

Because of the large number of other pathogens causing pneumonia, clinical signs and lesions can not be used for diagnosis. The presence of other infectious agents can also make diagnosis more difficult. Swabbing the trachea and collecting lung tissue for culture and histopathology is the standard diagnostic method. Culture and isolation of P.multocida are relatively easy to do. Remember that a positive sample from the upper respiratory tract (nasal swabs or oral fluids) is inconclusive.

Differential Diagnosis

When facing a case with pneumonia-like symptoms Streptococcus suis, Bordetella bronchiseptica, Actinobacillus suis, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Glaesserella parasuis, and Salmonella choleraesuis should also be considered.

What is the best way to diagnose P.multocida?

- PCR testing on nasal swab

- Culture of oral fluids

- Culture of lung tissues

- PCR testing of oropharyngeal swabs

Treatment, Prevention and Control

Antibiotic therapy by injection is the preferred method of treatment. P.multocida has been reported to be increasing in resistance to certain antibiotic treatments, so an antibiogram should be ran before deciding on a treatment. Usually, tetracyclines, cephalosporins, and macrolides tend to be effective. A vaccine has been developed but the effectiveness has not yet been determined. Rather, it is more effective to attempt and control primary respiratory pathogens, because without these, P.multocida does not cause disease.

Progressive Atrophic Rhinitis

Progressive Atrophic Rhinitis is a disease that affects the nose and parts of the upper respiratory tract in swine. It is caused by two main agents Bordetella bronchiseptica and Pasteurella multocida. Atrophic rhinitis starts with mild clinical signs, such as sneezing and snorting, but will progress into more severe symptoms that result in major nose damage. This disease is becoming increasingly rare, however, as effective treatment and control methods are being practiced.

Etiology and transmission

Bordetella bronchiseptica is the more common of the two causative agents and is well known, as it affects many other species, including dogs and cats. This gram-negative bacteria is commonly present in swine, but toxic strains are more rare. Its affect is mainly limited to the immunocompromised and as a promoter for more harmful strains of P.multocida.

P.multocida is gram negative bacteria with 5 serotypes. Type D is the main cause of atrophic rhinitis. Like most respiratory diseases, both of these bacteria are spread via nose-to-nose contact. B.bronchiseptica can also be spread short distances through the air, most commonly by sneezing. Both types of bacteria can remain viable for extended periods of time ( > 1 month) so contaminated environments are a concern.

Associated symptoms

Symptoms begin mildly, often through sneezing, snorting or light nasal discharge in growing pigs. If they are only infected with B.bronchiseptica and have a strong immune response, symptoms can last as short as two weeks. In immunocompromised animals or those infected with type D P.multocida, symptoms progress and continue through the entirety of the animal’s life.

The 2 bacteria work in synergy together: Bordetella first attaches to the nasal epithelium and destroys the cilia as well as the epithelium. It then starts to attack the underlying bone structure. Then, Pasteurella colonizes the exposed bone and contributes to the damage. Indeed, the toxin produced by Pasteurella affects the formation of bone within the nasal cavity. As a result the snout may not form correctly, displaying either as shorten upper jaw or lateral deviation. The nasal turbinates completely disappear in the most severe cases. This can cause feeding issues in the pig. The bacteria can also block tear ducts, causing staining near the inner corner of the eyes.

What clinical sign is mainly associated with Progressive Atrophic Rhinitis?

- Deviation of the snout

- Sudden death

- Coughing and dyspnea

Associated lesions

Macroscopic lesions

The most common macroscopic lesions of atrophic rhinitis occur in the nasal cavity. Septum deviation is expected and damage to the bones in the nasal cavity, snout, and even face is often present. This can be accompanied by mucus build up and possible ruptured blood vessels.

Microscopic lesions

There is often cell inflammation in the nasal cavity accompanied by a buildup of osteoclasts. The other lesion typically seen is replacement of bone with fibrous tissue.

What primary pathogen is needed to see signs of Progressive Atrophic Rhinitis?

- Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae

- Pasteurella multocida type D

- Bordetella bronchiseptica

Diagnosis

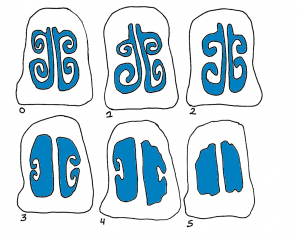

Clinical signs such as snout shortening or deviation, are often enough to diagnose Progressive Atrophic Rhinitis but culture of nasal swabs is the easiest and most cost effective way to identify the strains. ELISA tests can also be used to detect the presence of antibodies in serum. Additionally, observation of snouts at the slaughterhouse can help assess the herd status. Snouts are cut between the first and second premolar teeth and the cross-section is scored: 0 being a normal section, 1 showing the beginning of nasal turbinates atrophy, and 5 having no nasal turbinates left.

Picture: Snout showing clinical signs of Atrophic Rhinitis | Source: Dr. Carlos Pijoan

Figure: Rhinitis scores from 0 to 5 | Source: Dr. Perle Zhitnitskiy

Treatment, Prevention and Control

A holistic approach to treating and controlling Progressive Atrophic Rhinitis is preferred due to the number of contributing factors to this disease. Keeping a clean environment, including adequate ventilation, is important, because excessive dust can inhibit the local immune response in the nose. Vaccines are available for both B.bronchiseptica and P. multocida, usually given to the sows shortly before farrowing to increase piglets’ protection against the disease. Antimicrobial treatment is possible, but one needs to be mindful of resistances. However, once the lesions have started, it is only possible to stop the progression of the disease. Tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and macrolides can be used.

Eradication of the disease in the long term should be the priority. Elimination of the pathogens, by depopulation and repopulation with a naive dam has been successful.