Reproductive System

Porcine Parvovirus

Clinical importance

Porcine Parvovirus (PPV) is one of the most important causes of swine reproductive failure worldwide. The virus is ubiquitous in the environment and particularly resistant due to its non-enveloped structure. The infected sow does not show symptoms until the gestation and sometimes farrowing. Fetal infection occurring between gestation day 35 and 70 typically results in fetal death. However, prevalence is rare in the US due to vaccination protocols put in place in the vast majority of sow herds.

Etiology and Transmission

PPV is a non-enveloped, DNA virus. It is spread oro-nasally through feces and other secretions from infected pigs. It is stable in regards to both temperature and chemicals and can be transferred via fomites such as clothes, boots, or equipment that is not properly disinfected. The virus can also be introduced into a herd via semen of an infected boar. Lastly, PPV can cross the placenta and be transmitted from the sow to its offspring in utero.

Associated symptoms

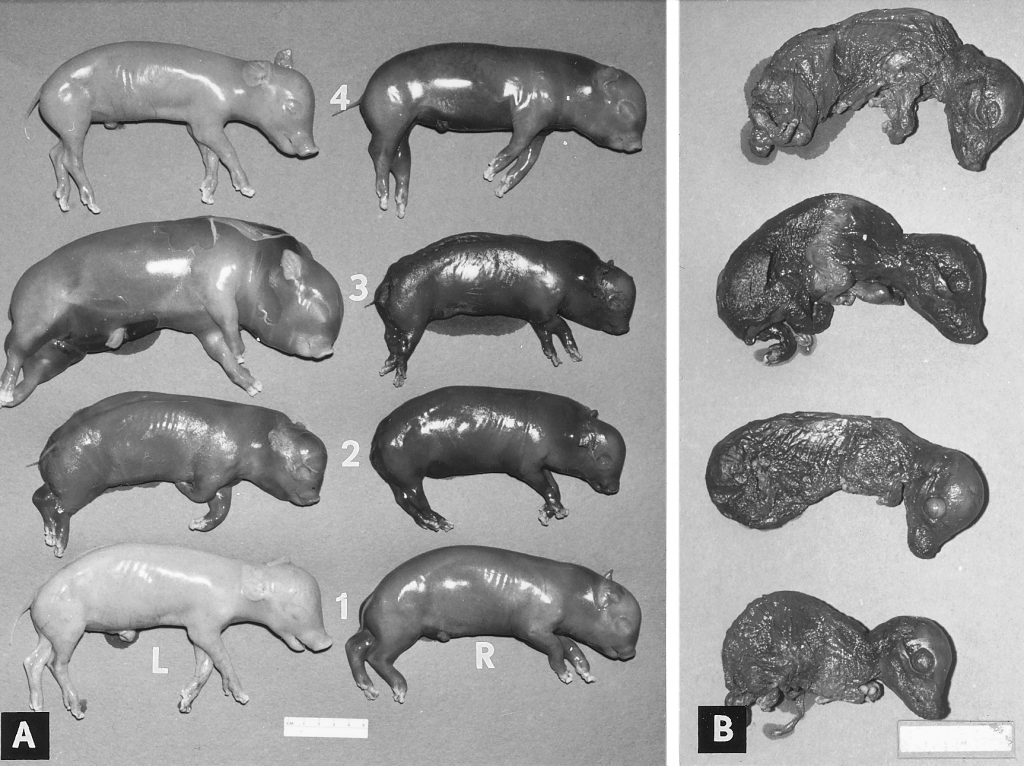

The main clinical sign of PPV is maternal reproductive failure. The main forms of reproductive failure are embryo death or reabsorption as well as mummies from different lengths. Once in the uterus, the virus spreads from one fetus to the next instead of infecting them all at the same time. If the sow gets infected after bone development (around day 35 of gestation), mummification begins; otherwise embryos are reabsorbed and the sow returns into estrus. Therefore, the characteristic “Parvo litter” consists of mummified piglets of progressively larger size. Abortions are quite rare. Minor clinical signs in sows are diarrhea and skin lesions.

Mummified fetuses from an experimentally infected sow. Courtesy of Mengeling et al. 1975. Public domain

Associated lesions

Macroscopic lesions

Gross lesions in gilts, sows, and boars associated with PPV are non-existent. However, fetuses do display some macroscopic lesions. Typically, fetuses become mummified through fluid reabsorption and display a change in color from yellowish-brown to black. Once the fetus is infected and dies; growth stops, leading to various sizes of mummified fetuses at birth.

Microscopic lesions

Microscopic lesions are not very indicative of a parvovirus infection. Mainly, perivascular cuffing is seen in tissues. Other histopathological changes to look for include necrosis and mineralization of cells in developing organ systems, especially in the heart and lungs.

Diagnosis

Clinical observation is the first step to make a parvovirus diagnosis. Indeed, a mixed litter of born alive piglets and mummified fetuses of increasing size should put PPV in your differential list. Remember though that abortions due to PPV are a rare occurrence. Even though immunofluorescence testing of fetal tissue for viral antigen is the gold standard, PCR on tissue homogenate is more commonly done due to a faster turnaround time. Hemagglutination inhibition can also be done on fetal fluids.

If some piglets of the litter are born alive, serology testing for PPV antibodies could be used since fetuses infected with the virus after day 70 days of gestation are born with anti-PPV antibodies. Sow serology can be used when fetal samples are not available, however there are many challenges in interpreting the results. A positive result does not necessarily mean that PPV is the cause, rather it indicates that the sow has been exposed to the virus at some point in time, either through natural infection or through vaccination.

Differential diagnostic

When you are facing a clinical case with mummified fetuses, other diseases to consider are PRRS, PCV2, pseudorabies, leptospirosis, brucellosis, and Erysipelas (rare).

Treatment, Prevention and Control

Remember that the virus is found worldwide and that it can resist for a long time in the environment. Research has shown that it can remain infectious for up to 4 months.

Killed vaccines are very effective at preventing clinical signs and they have been used with success to main herd-level immunity against PPV. Therefore, a robust vaccination program for gilts, sows and boars is more appropriate than herd elimination. Typically, sows are primo-vaccinated as gilts before their first breeding, and received a booster at each parity after weaning. Due to the stability of the virus in the environment, preventing the transport of the disease between herds through biosecurity measures is critical, especially with unvaccinated herds.

Published on: July 30, 2018