6.5 Competing When Network Effects Matter

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Plot strategies for competing in markets where network effects are present, both from the perspective of the incumbent firm and the new market entrant.

- Give examples of how firms have leveraged these strategies to compete effectively.

Why do you care whether networks are one-sided, two-sided, or some sort of hybrid? Well, when crafting your plan for market dominance, it’s critical to know if network effects exist, how strong they might be, where they come from, and how they might be harnessed to your benefit. Here’s a quick rundown of the tools at your disposal when competing in the presence of network effects.

Strategies for Competing in Markets with Network Effects (Examples in Parentheses)

- Move early (Yahoo! Auctions in Japan)

- Subsidize product adoption (PayPal)

- Leverage viral promotion (Skype; Facebook feeds)

- Expand by redefining the market to bring in new categories of users (Nintendo Wii) or through convergence (iPhone).

- Form alliances and partnerships (NYCE vs. Citibank)

- Establish distribution channels (Java with Netscape; Microsoft bundling Media Player with Windows)

- Seed the market with complements (Blu-ray; Nintendo)

- Encourage the development of complementary goods—this can include offering resources, subsidies, reduced fees, market research, development kits, venture capital (Facebook fbFund).

- Maintain backward compatibility (Apple’s Mac OS X Rosetta translation software for PowerPC to Intel)

- For rivals, be compatible with larger networks (Apple’s move to Intel; Live Search Maps)

- For incumbents, constantly innovate to create a moving target and block rival efforts to access your network (Apple’s efforts to block access to its own systems)

- For large firms with well-known followers, make preannouncements (Microsoft)

Move Early

In the world of network effects, this is a biggie. Being first allows your firm to start the network effects snowball rolling in your direction. In Japan, worldwide auction leader eBay showed up just five months after Yahoo! launched its Japanese auction service. But eBay was never able to mount a credible threat and ended up pulling out of the market. Being just five months late cost eBay billions in lost sales, and the firm eventually retreated, acknowledging it could never unseat Yahoo!’s network effects lead.

Another key lesson from the loss of eBay Japan? Exchange depends on the ability to communicate! EBay’s huge network effects in the United States and elsewhere didn’t translate to Japan because most Japanese aren’t comfortable with English, and most English speakers don’t know Japanese. The language barrier made Japan a “greenfield” market with no dominant player, and Yahoo!’s early move provided the catalyst for victory.

Timing is often critical in the video game console wars, too. Sony’s PlayStation 2 enjoyed an eighteen-month lead over the technically superior Xbox (as well as Nintendo’s GameCube). That time lead helped to create what for years was the single most profitable division at Sony. By contrast, the technically superior PS3 showed up months after Xbox 360 and at roughly the same time as the Nintendo Wii, and has struggled in its early years, racking up multibillion-dollar losses for Sony (Null, 2008).

What If Microsoft Threw a Party and No One Showed Up?

Microsoft launched the Zune media player with features that should be subject to network effects—the ability to share photos and music by wirelessly “squirting” content to other Zune users. The firm even promoted Zune with the tagline “Welcome to the Social.” Problem was the Zune Social was a party no one wanted to attend. The late-arriving Zune garnered a market share of just 3 percent, and users remained hard pressed to find buddies to leverage these neat social features (Walker, 2008). A cool idea does not make a network effect happen.

Subsidize Adoption

Starting a network effect can be tough—there’s little incentive to join a network if there’s no one in the system to communicate with. In one admittedly risky strategy, firms may offer to subsidize initial adoption in hopes that network effects might kick in shortly after. Subsidies to adopters might include a price reduction, rebate, or other giveaways. PayPal, a service that allows users to pay one another using credit cards, gave users a modest rebate as a sign-up incentive to encourage adoption of its new effort (in one early promotion, users got back fifteen dollars when spending their first thirty dollars). This brief subsidy paid to early adopters paid off handsomely. EBay later tried to enter the market with a rival effort, but as a late mover its effort was never able to overcome PayPal’s momentum. PayPal was eventually purchased by eBay for $1.5 billion, and the business unit is now considered one of eBay’s key drivers of growth and profit.

When Even Free Isn’t Good Enough

Subsidizing adoption after a rival has achieved dominance can be an uphill battle, and sometimes even offering a service for free isn’t enough to combat the dominant firm. When Yahoo! introduced a U.S. auction service to compete with eBay, it initially didn’t charge sellers at all (sellers typically pay eBay a small percentage of each completed auction). The hope was that with the elimination of seller fees, enough sellers would jump from eBay to Yahoo! helping the late-mover catch up in the network effect game.

But eBay sellers were reluctant to leave for two reasons. First, there weren’t enough buyers on Yahoo! to match the high bids they earned on much-larger eBay. Some savvy sellers played an arbitrage game where they’d buy items on Yahoo!’s auction service at lower prices and resell them on eBay, where more users bid prices higher.

Second, any established seller leaving eBay would give up their valuable “seller ratings,” and would need to build their Yahoo! reputation from scratch. Seller ratings represent a critical switching cost, as many users view a high rating as a method for reducing the risk of getting scammed or receiving lower-quality goods.

Auctions work best for differentiated goods. While Amazon has had some success in peeling away eBay sellers who provide commodity products (a real danger as eBay increasingly relies on fixed-price sales), eBay’s dominant share of the online auction market still towers over all rivals (Stone, 2008). While there’s no magic in the servers used to create eBay, the early use of technology allowed the firm to create both network effects and switching costs—a dual strategic advantage that has given it a hammerlock on auctions even as others have attempted to mimic its service and undercut its pricing model.

Leverage Viral Promotion

Since all products and services foster some sort of exchange, it’s often possible to leverage a firm’s customers to promote the product or service. Internet calling service Skype has over five hundred million registered users yet has spent almost nothing on advertising. Most Skype users were recruited by others who shared the word on free and low-cost Internet calls. Within Facebook, feeds help activities to spread virally (see Chapter 8 “Facebook: Building a Business from the Social Graph”). Feeds blast updates on user activities on the site, acting as a catalyst for friends to join groups and load applications that their buddies have already signed up for.

Expand by Redefining the Market

If a big market attracts more users (and in two-sided markets, more complements), why not redefine the space to bring in more users? Nintendo did this when launching the Wii. While Sony and Microsoft focused on the graphics and raw processing power favored by hard-core male gamers, Nintendo chose to develop a machine to appeal to families, women, and age groups that normally shunned alien shoot-’em ups. By going after a bigger, redefined market, Nintendo was able to rack up sales that exceeded the Xbox 360, even though it followed the system by twelve months (Sanchanta, 2007).

Seeking the Blue Ocean

Reggie Fils-Aimé, the President of Nintendo of America, describes the Wii Strategy as a Blue Ocean effort (Fils-Aimé, 2009). The concept of blue ocean strategy was popularized by European Institute of Business Administration (INSEAD) professors W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne (authors of a book with the same title) (Kim & Mauborgne, 2005). The idea—instead of competing in blood-red waters where the sharks of highly competitive firms vie for every available market scrap, firms should seek the blue waters of uncontested, new market spaces.

For Nintendo, the granny gamers, moms, and partygoers who flocked to the Wii represented an undiscovered feast in the Blue Ocean. Talk about new markets! Consider that the best-selling video game at the start of 2009 was Wii Fit—a genre-busting title that comes with a scale so you can weigh yourself each time you play! That’s a far cry from Grand Theft Auto IV, the title ranking fifth in 2008 sales, and trailing four Wii-only exclusives.

Blue ocean strategy often works best when combined with strategic positioning described in Chapter 2 “Strategy and Technology: Concepts and Frameworks for Understanding What Separates Winners from Losers”. If an early mover into a blue ocean can use this lead to create defensible assets for sustainable advantage, late moving rivals may find markets unresponsive to their presence.

Market expansion sometimes puts rivals who previously did not compete on a collision course as markets undergo convergence (when two or more markets, once considered distinctly separate, begin to offer similar features and capabilities). Consider the market for portable electronic devices. Separate product categories for media players, cameras, gaming devices, phones, and global positioning systems (GPS) are all starting to merge. Rather than cede its dominance as a media player, Apple leveraged a strategy known as envelopment, where a firm seeks to make an existing market a subset of its product offering. Apple deftly morphed the iPod into the iPhone, a device that captures all of these product categories in one device. But the firm went further; the iPhone is Wi-Fi capable, offers browsing, e-mail, and an application platform based on a scaled-down version of the same OS X operating system used in Macintosh computers. As a “Pocket Mac,” the appeal of the device broadened beyond just the phone or music player markets, and within two quarters of launch, iPhone become the second-leading smartphone in North America—outpacing Palm, Microsoft, Motorola and every other rival, except RIM’s BlackBerry (Kim, 2007).

Alliances and Partnerships

Firms can also use partnerships to grow market share for a network. Sometimes these efforts bring rivals together to take out a leader. In a classic example, consider ATM networks. Citibank was the first major bank in New York City to offer a large ATM network. But the Citi network was initially proprietary, meaning customers of other banks couldn’t take advantage of Citi ATMs. Citi’s innovation was wildly popular and being a pioneer in rolling out cash machines helped the firm grow deposits fourfold in just a few years. Competitors responded with a partnership. Instead of each rival bank offering another incompatible network destined to trail Citi’s lead, competing banks agreed to share their ATM operations through NYCE (New York Cash Exchange). While Citi’s network was initially the biggest, after the NYCE launch a Chase bank customer could use ATMs at a host of other banks that covered a geography far greater than Citi offered alone. Network effects in ATMs shifted to the rival bank alliance, Citi eventually joined NYCE and today, nearly every ATM in the United States carries a NYCE sticker.

Google has often pushed an approach to encourage rivals to cooperate to challenge a leader. Its Open Social standard for social networking (endorsed by MySpace, LinkedIn, Bebo, Yahoo! and others) is targeted at offering a larger alternative to Facebook’s more closed efforts (see Chapter 8 “Facebook: Building a Business from the Social Graph”), while its Android open source mobile phone operating system has gained commitments from many handset makers that collectively compete with Apple’s iPhone.

Share or Stay Proprietary?

Defensive moves like the ones above are often meant to diffuse the threat of a proprietary rival. Sometimes firms decide from the start to band together to create a new, more open standard, realizing that collective support is more likely to jumpstart a network than if one firm tried to act with a closed, proprietary offering. Examples of this include the coalitions of firms that have worked together to advance standards like Bluetooth and Wi-Fi. While no single member firm gains a direct profit from the sale of devices using these standards, the standard’s backers benefit when the market for devices expands as products become more useful because they are more interoperable.

Leverage Distribution Channels

Firms can also think about novel ways to distribute a product or service to consumers. Sun faced a challenge when launching the Java programming language—no computers could run it. In order for Java to work, computers need a little interpreter program called the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). Most users weren’t willing to download the JVM if there were no applications written in Java, and no developers were willing to write in Java if no one could run their code. Sun broke the logjam when it bundled the JVM with Netscape’s browser. When millions of users downloaded Netscape, Sun’s software snuck in, almost instantly creating a platform of millions for would-be Java developers. Today, even though Netscape has failed, Sun’s Java remains one of the world’s most popular programming languages. Indeed, Java was cited as one of the main reasons for Oracle’s 2009 acquisition of Sun, with Oracle’s CEO saying the language represented “the single most important software asset we have ever acquired” (Ricadela, 2009).

As mentioned in Chapter 2 “Strategy and Technology: Concepts and Frameworks for Understanding What Separates Winners from Losers”, Microsoft is in a particularly strong position to leverage this approach. The firm often bundles its new products into its operating systems, Office suite, Internet Explorer browser, and other offerings. The firm used this tactic to transform once market-leader Real Networks into an also-ran in streaming audio. Within a few years of bundling Windows Media Player (WMP) with its other products, WMP grabbed the majority of the market, while Real’s share had fallen to below 10 percent1 (Eisenmann et. al., 2006).

Caution is advised, however. Regional antitrust authorities may consider product bundling by dominant firms to be anticompetitive. European regulators have forced Microsoft to unbundle Windows Media Player from its operating system and to provide a choice of browsers alongside Internet Explorer.

Antitrust: Real Versus Microsoft

From October 2001 to March 2003, Microsoft’s bundling of Windows Media Player in versions of its operating system ensured that the software came preinstalled on nearly all of the estimated 207 million new PCs shipped during that period. By contrast, Real Networks’ digital media player was preinstalled on less than 2 percent of PCs. But here’s the kicker that got to regulators (and Real): Microsoft’s standard contract with PC manufacturers “prevented them not only from removing the Windows Media Player, but even [from] providing a desktop icon for Real Networks” (Hansen & Becker, 2003; Eisenmann et. al., 2006). While network effects create monopolies, governments may balk at allowing a firm to leverage its advantages in ways that are designed to deliberately keep rivals from the market.

Seed the Market

When Sony launched the PS3, it subsidized each console by selling at a price estimated at three hundred dollars below unit cost (Null, 2008). Subsidizing consoles is a common practice in the video game industry—game player manufacturers usually make most of their money through royalties paid by game developers. But Sony’s subsidy had an additional benefit for the firm—it helped sneak a Blu-ray player into every home buying a PS3 (Sony was backing the Blu-ray standard over the rival HD DVD effort). Since Sony is also a movie studio and manufacturer of DVD players and other consumer electronics, it had a particularly strong set of assets to leverage to encourage the adoption of Blu-ray over rival HD DVD.

Giving away products for half of a two-sided market is an extreme example of this kind of behavior, but it’s often used. In two-sided markets, you charge the one who will pay. Adobe gives away the Acrobat reader to build a market for the sale of software that creates Acrobat files. Firms with Yellow Page directories give away countless copies of their products, delivered straight to your home, in order to create a market for selling advertising. And Google does much the same by providing free, ad-supported search.

Encourage the Development of Complementary Goods

There are several ways to motivate others to create complementary goods for your network. These efforts often involve some form of developer subsidy or other free or discounted service. A firm may charge lower royalties or offer a period of royalty-free licensing. It can also offer free software development kits (SDKs), training programs, co-marketing dollars, or even start-up capital to potential suppliers. Microsoft and Apple both allow developers to sell their products online through Xbox LIVE Marketplace and iTunes, respectively. This channel lowers developer expenses by eliminating costs associated with selling physical inventory in brick-and-mortar stores and can provide a free way to reach millions of potential consumers without significant promotional spending.

Venture funds can also prompt firms to create complementary goods. Facebook announced it would spur development for the site in part by administering the fbFund, which initially pledged $10 million in start-up funding (in allotments of up to $250,000 each) to firms writing applications for its platform.

Leverage Backward Compatibility

Those firms that control a standard would also be wise to ensure that new products have backward compatibility with earlier offerings. If not, they reenter a market at installed-base zero and give up a major source of advantage—the switching costs built up by prior customers. For example, when Nintendo introduced its 16-bit Super Nintendo system, it was incompatible with the firm’s highly successful prior generation 8-bit model. Rival Sega, which had entered the 16-bit market two years prior to Nintendo, had already built up a large library of 16-bit games for its system. Nintendo entered with only its debut titles, and no ability to play games owned by customers of its previous system, so there was little incentive for existing Nintendo fans to stick with the firm (Schilling, 2003).

Backward compatibility was the centerpiece of Apple’s strategy to revitalize the Macintosh through its move to the Intel microprocessor. Intel chips aren’t compatible with the instruction set used by the PowerPC processor used in earlier Mac models. Think of this as two entirely different languages—Intel speaks French, PowerPC speaks Urdu. To ease the transition, Apple included a free software-based adaptor, called Rosetta, that automatically emulated the functionality of the old chip on all new Macs (a sort of Urdu to French translator). By doing so, all new Intel Macs could use the base of existing software written for the old chip; owners of PowerPC Macs were able to upgrade while preserving their investment in old software; and software firms could still sell older programs while they rewrote applications for new Intel-based Macs.

Even more significant, since Intel is the same standard used by Windows, Apple developed a free software adaptor called Boot Camp that allowed Windows to be installed on Macs. Boot Camp (and similar solutions by other vendors) dramatically lowered the cost for Windows users to switch to Macs. Within two years of making the switch, Mac sales skyrocketed to record levels. Apple now boasts a commanding lead in notebook sales to the education market (Seitz, 2008), and a survey by Yankee Group found that 87 percent of corporations were using at least some Macintosh computers, up from 48 percent at the end of the PowerPC era two years earlier (Burrows, 2008).

Rivals: Be Compatible with the Leading Network

Companies will want to consider making new products compatible with the leading standard. Microsoft’s Live Maps and Virtual Earth 3D arrived late to the Internet mapping game. Users had already put in countless hours building resources that meshed with Google Maps and Google Earth. But by adopting the same keyhole markup language (KML) standard used by Google, Microsoft could, as TechCrunch put it, “drink from Google’s milkshake.” Any work done by users for Google in KML could be used by Microsoft. Voilà, an instant base of add-on content!

Incumbents: Close Off Rival Access and Constantly Innovate

Oftentimes firms that control dominant networks will make compatibility difficult for rivals who try to connect with their systems. AOL has been reluctant to open up its instant messaging tool to rivals, and Skype for years had been similarly closed to non-Skype clients.

Firms that constantly innovate make it particularly difficult for competitors to become compatible. Again, we can look to Apple as an example of these concepts in action. While Macs run Windows, Windows computers can’t run Mac programs. Apple has embedded key software in Mac hardware, making it tough for rivals to write a software emulator like Boot Camp that would let Windows PCs drink from the Mac milkshake. And if any firm gets close to cloning Mac hardware, Apple sues. The firm also modifies software on other products like the iPhone and iTunes each time wily hackers tap into closed aspects of its systems. And Apple has regularly moved to block third-party hardware, such as Palm’s mobile phones, from plugging into iTunes. Even if firms create adaptors that emulate a standard, a firm that constantly innovates creates a moving target that’s tough for others to keep up with.

Apple has been far more aggressive than Microsoft in introducing new versions of its software. Since the firm never stays still, would-be cloners never get enough time to create a reliable emulator that runs the latest Apple software.

Large, Well-Known Followers: Preannouncements

Large firms that find new markets attractive but don’t yet have products ready for delivery might preannounce efforts in order to cause potential adaptors to sit on the fence, delaying a purchasing decision until the new effort rolls out. Preannouncements only work if a firm is large enough to pose a credible threat to current market participants. Microsoft, for example, can cause potential customers to hold off on selecting a rival because users see that the firm has the resources to beat most players (suggesting staying power). Statements from start-ups, however, often lack credibility to delay user purchases. The tech industry acronym for the impact firms try to impart on markets through preannouncements is FUD for fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

The Osborne Effect

Preannouncers, beware. Announce an effort too early and a firm may fall victim to what’s known as “The Osborne Effect.” It’s been suggested that portable computer manufacturer Osborne Computer announced new models too early. Customers opted to wait for the new models, so sales of the firm’s current offerings plummeted. While evidence suggests that Osborne’s decline had more to do with rivals offering better products, the negative impact of preannouncements has hurt a host of other firms (Orlowski, 2005). Among these, Sega, which exited the video game console market entirely after preannouncements of a next-generation system killed enthusiasm for its Saturn console (Schilling, 2003).

Too Much of a Good Thing?

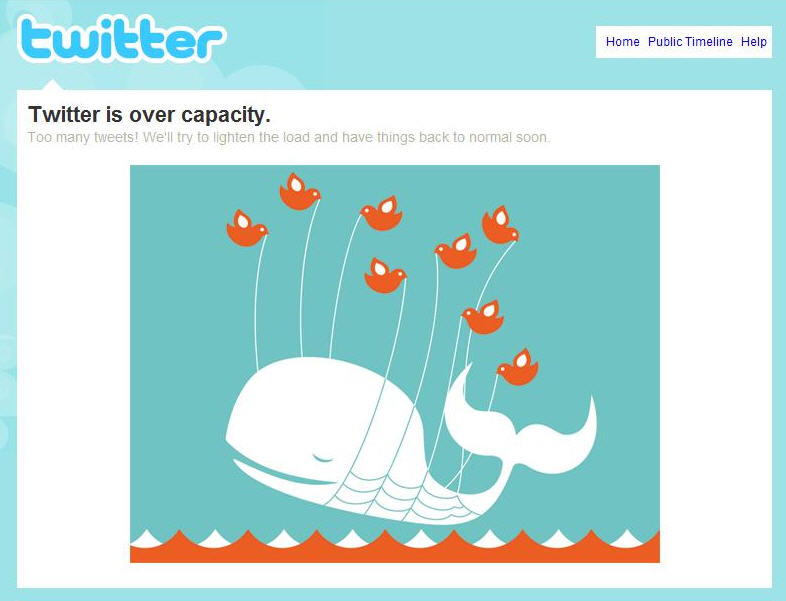

When network effects are present, more users attract more users. That’s a good thing as long as a firm can earn money from this virtuous cycle. But sometimes a network effect attracts too many users and a service can be so overwhelmed it becomes unusable. These so-called congestion effects occur when increasing numbers of users lower the value of a product or service. This most often happens when a key resource becomes increasingly scarce. Users of the game Ultima were disappointed in an early online version that launched without enough monsters to fight or server power to handle the crush of fans. Twitter’s early infrastructure was often unable to handle the demands of a service in hypergrowth (leading to the frequent appearance of a not-in-service graphic known in the Twitter community as the “fail whale”). Facebook users with a large number of friends may also find their attention is a limited resource, as feeds push so much content that it becomes difficult to separate interesting information from the noise of friend actions.

And while network effects can attract positive complementary products, a dominant standard may also be the first place where virus writers and malicious hackers choose to strike.

Feel confident! Now you’ve got a solid grounding in network effects, the key resource leveraged by some of the most dominant firms in technology. And these concepts apply beyond the realm of tech, too. Network effects can explain phenomena ranging from why some stock markets are more popular than others to why English is so widely spoken, even among groups of nonnative speakers. On top of that, the strategies explored in the last half of the chapter show how to use these principles to sniff out, create, and protect this key strategic asset. Go forth, tech pioneer—opportunity awaits!

Key Takeaways

- Moving early matters in network markets—firms that move early can often use that time to establish a lead in users, switching costs, and complementary products that can be difficult for rivals to match.

- Additional factors that can help a firm establish a network effects lead include subsidizing adoption; leveraging viral marketing, creating alliances to promote a product or to increase a service’s user base; redefining the market to appeal to more users; leveraging unique distribution channels to reach new customers; seeding the market with complements; encouraging the development of complements; and maintaining backward compatibility.

- Established firms may try to make it difficult for rivals to gain compatibility with their users, standards, or product complements. Large firms may also create uncertainty among those considering adoption of a rival by preannouncing competing products.

Questions and Exercises

- Is market entry timing important for network effects markets? Explain and offer an example to back up your point.

- How might a firm subsidize adoption? Give an example.

- Give an example of a partnership or alliance targeted at increasing network effects.

- Is it ever advantageous for firms to give up control of a network and share it with others? Why or why not? Give examples to back up your point.

- Do firms that dominate their markets with network effects risk government intervention? Why or why not? Explain through an example.

- How did Sony seed the market for Blu-ray players?

- What does backward compatibility mean and why is this important? What happens if a firm is not backward compatible?

- What tactic did Apple use to increase the acceptability of the Mac platform to a broader population of potential users?

- How has Apple kept clones at bay?

- What are preannouncements? What is the danger in announcing a product too early? What is the term for negative impacts from premature product announcements?

- How did PayPal subsidize adoption?

- Name two companies that leveraged viral promotion to compete.

- Name a product that is the result of the convergence of media players, cameras, and phones.

- What is bundling? What are the upsides and downsides of bundling?

- Why does Adobe allow the free download of Acrobat Reader?

- What tactic might an established firm employ to make it impossible, or at least difficult, for a competitor to gain access to, or become compatible with, their product or service?

- How do Apple, Microsoft, and Facebook encourage the development of complementary products?

- What is the “congestion effect”? Give an example.

- Do network effects apply in nontech areas? Give examples.

1BusinessWire, “Media Player Format Share for 2006 Confirms Windows Media Remains Dominant with a 50.8% Share of Video Streams Served, Followed by Flash at 21.9%—‘CDN Growth and Market Share Shifts: 2002–2006,’” December 18, 2006.

References

Burrows, P., “The Mac in the Gray Flannel Suit,” BusinessWeek, May 1, 2008.

Eisenmann, T., G. Parker, and M. Van Alstyne, “Strategies for Two-Sided Markets,” Harvard Business Review, October 2006.

Fils-Aimé, R., (presentation and discussion, Carroll School of Management, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA, April 6, 2009).

Hansen, E. and D. Becker, “Real Hits Microsoft with $1 Billion Antitrust Suit,” CNET, December 18, 2003, http://news.cnet.com/Real-hits-Microsoft-with-1-billion -antitrust-suit/2100-1025_3-5129316.html.

Kim, R., “iPhone No. 2 Smartphone Platform in North America,” The Tech Chronicles—The San Francisco Chronicle, December 17, 2007.

Kim, W. C. and R. Mauborgne, Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make Competition Irrelevant (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2005). See http://www.blueoceanstrategy.com.

Null, C., “Sony’s Losses on PS3: $3 Billion and Counting,” Yahoo! Today in Tech, June 27, 2008, http://tech.yahoo.com/blogs/null/96355.

Orlowski, A., “Taking Osborne out of the Osborne Effect,” The Register, June 20, 2005.

Ricadela, A., “Oracle’s Bold Java Plans,” BusinessWeek, June 2, 2009.

Sanchanta, M., “Nintendo’s Wii Takes Console Lead,” Financial Times, September 12, 2007.

Schilling, M., “Technological Leapfrogging: Lessons from the U.S. Video Game Console Industry,” California Management Review, Spring 2003.

Seitz, P., “An Apple for Teacher, Students: Mac Maker Surges in Education,” Investor’s Business Daily, August 8, 2008.

Stone, B., “Amid the Gloom, an E-commerce War,” New York Times, October 12, 2008.

Walker, R., “AntiPod,” New York Times, August 8, 2008.