6.4 How Are These Markets Different?

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand how competition in markets where network effects are present differ from competition in traditional markets.

- Understand the reasons why it is so difficult for late-moving, incompatible rivals to compete in markets where a dominant, proprietary standard is present.

When network effects play a starring role, competition in an industry can be fundamentally different than in conventional, nonnetwork industries.

First, network markets experience early, fierce competition. The positive-feedback loop inherent in network effects—where the biggest networks become even bigger—causes this. Firms are very aggressive in the early stages of these industries because once a leader becomes clear, bandwagons form, and new adopters begin to overwhelmingly favor the leading product over rivals, tipping the market in favor of one dominant firm or standard. This tipping can be remarkably swift. Once the majority of major studios and retailers began to back Blu-ray over HD DVD, the latter effort folded within weeks.

These markets are also often winner-take-all or winner-take-most, exhibiting monopolistic tendencies where one firm dominates all rivals. Look at all of the examples listed so far—in nearly every case the dominant player has a market share well ahead of all competitors. When, during the U.S. Microsoft antitrust trial, Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson declared Microsoft to be a monopoly (a market where there are many buyers but only one dominant seller), the collective response should have been “of course.” Why? The natural state of a market where network effects are present (and this includes operating systems and Office software) is for there to be one major player. Since bigger networks offer more value, they can charge customers more. Firms with a commanding network effects advantage may also enjoy substantial bargaining power over partners. For example, Apple, which controls over 75 percent of digital music sales, for years was able to dictate song pricing, despite the tremendous protests of the record labels (Barnes, 2007). In fact, Apple’s stranglehold was so strong that it leveraged bargaining power even though the “Big Four” record labels (Universal, Sony, EMI, and Warner) were themselves an oligopoly (a market dominated by a small number of powerful sellers) that together provide over 85 percent of music sold in the United States.

Finally, it’s important to note that the best product or service doesn’t always win. PlayStation 2 dominated the video console market over the original Xbox, despite the fact that nearly every review claimed the Xbox was hands-down a more technically superior machine. Why were users willing to choose an inferior product (PS2) over a superior one (Xbox)? The power of network effects! PS2 had more users, which attracted more developers offering more games.

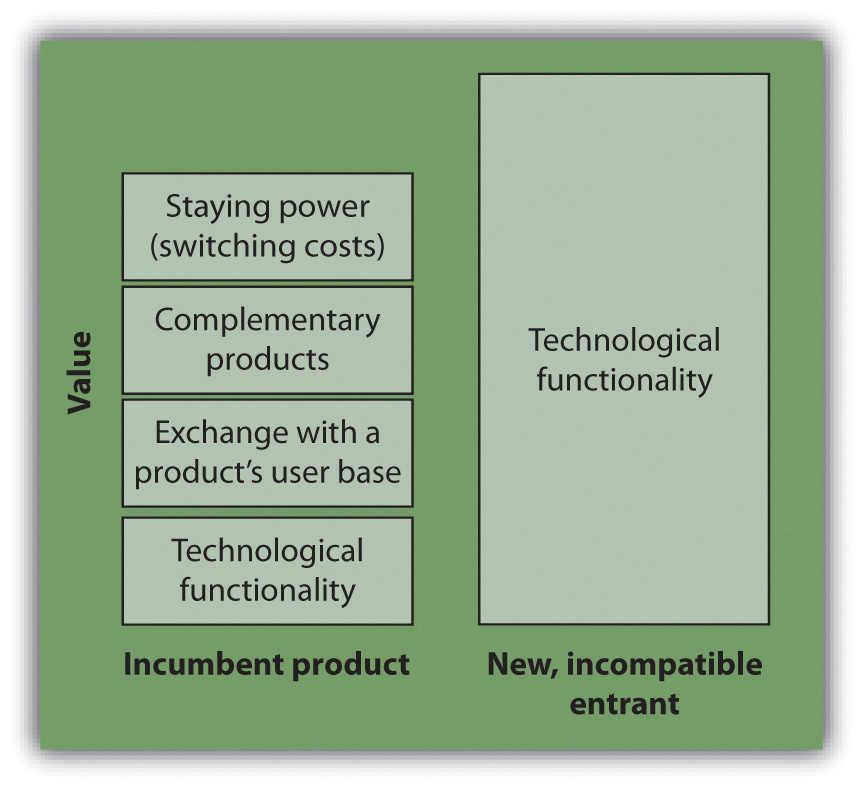

This last note is a critical point to any newcomer wishing to attack an established rival. Winning customers away from a dominant player in a network industry isn’t as easy as offering a product or service that is better. Any product that is incompatible with the dominant network has to exceed the value of the technical features of the leading player, plus (since the newcomer likely starts without any users or third-party product complements) the value of the incumbent’s exchange, switching cost, and complementary product benefit (see Figure 6.1). And the incumbent must not be able to easily copy any of the newcomer’s valuable new innovations; otherwise the dominant firm will quickly match any valuable improvements made by rivals. As such, technological leapfrogging, or competing by offering a superior generation of technology, can be really tough (Schilling, 2003).

Is This Good for Innovation?

Critics of firms that leverage proprietary standards for market dominance often complain that network effects are bad for innovation. But this statement isn’t entirely true. While network effects limit competition against the dominant standard, innovation within a standard may actually blossom. Consider Windows. Microsoft has a huge advantage in the desktop operating system market, so few rivals try to compete with it. Apple’s Mac OS and the open source Linux operating system are the firm’s only credible rivals, and both have tiny market shares. But the dominance of Windows is a magnet for developers to innovate within the standard. Programmers with novel ideas are willing to make the investment in learning to write software for Windows because they’re sure that a Windows version can be used by the overwhelming majority of computer users.

By contrast, look at the mess we initially had in the mobile phone market. With so many different handsets offering different screen sizes, running different software, having different key layouts, and working on different carrier networks, writing a game that’s accessible by the majority of users is nearly impossible. Glu Mobile, a maker of online games, launched fifty-six reengineered builds of Monopoly to satisfy the diverse requirements of just one telecom carrier (Hutheesing, 2006). As a result, entrepreneurs with great software ideas for the mobile market were deterred because writing, marketing, and maintaining multiple product versions is both costly and risky. It wasn’t until Apple’s iPhone arrived, offering developers both a huge market and a consistent set of development standards, that third-party software development for mobile phones really took off.

Key Takeaways

- Unseating a firm that dominates with network effects can be extremely difficult, especially if the newcomer is not compatible with the established leader. Newcomers will find their technology will need to be so good that it must leapfrog not only the value of the established firm’s tech, but also the perceived stability of the dominant firm, the exchange benefits provided by the existing user base, and the benefits from any product complements. For evidence, just look at how difficult it’s been for rivals to unseat the dominance of Windows.

- Because of this, network effects might limit the number of rivals that challenge a dominant firm. But the establishment of a dominant standard may actually encourage innovation within the standard, since firms producing complements for the leader have faith the leader will have staying power in the market.

Questions and Exercises

- How is competition in markets where network effects are present different from competition in traditional markets?

- What are the reasons it is so difficult for late-moving, incompatible rivals to compete in markets where a dominant, proprietary standard is present? What is technological leapfrogging and why is it so difficult to accomplish?

- Does it make sense to try to prevent monopolies in markets where network effects exist?

- Are network effects good or bad for innovation? Explain.

- What is the relationship between network effects and the bargaining power of participants in a network effects “ecosystem”?

- Cite examples where the best technology did not dominate a network effects-driven market.

1Adapted from J. Gallaugher and Y. Wang, “Linux vs. Windows in the Middle Kingdom: A Strategic Valuation Model for Platform Competition” (paper, Proceedings of the 2008 Meeting of Americas Conference on Information Systems, Toronto, CA, August 2008), extending M. Schilling, “Technological Leapfrogging: Lessons from the U.S. Video Game Console Industry,” California Management Review, Spring 2003.

References

Barnes, B., “NBC Will Not Renew iTunes Contract,” New York Times, August 31, 2007.

Hutheesing, N., “Answer Your Phone, a Videogame Is Calling,” Forbes, August 8, 2006.

Schilling, M., “Technological Leapfrogging: Lessons from the U.S. Video Game Console Industry,” California Management Review, Spring 2003.