14.5 Ad Networks—Distribution beyond Search

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand ad networks, and how ads are distributed and served based on Web site content.

- Recognize how ad networks provide advertiser reach and support niche content providers.

- Be aware of content adjacency problems and their implications.

- Know the strategic factors behind ad network appeal and success.

Google runs ads not just in search, but also across a host of Google-owned sites like Gmail, Google News, and Blogger. It will even tailor ads for its map products and for mobile devices. But about 30 percent of Google’s revenues come from running ads on Web sites that the firm doesn’t even own1.

Next time you’re surfing online, look around the different Web sites that you visit and see how many sport boxes labeled “Ads by Google.” Those Web sites are participating in Google’s AdSense ad network, which means they’re running ads for Google in exchange for a cut of the take. Participants range from small-time bloggers to some of the world’s most highly trafficked sites. Google lines up the advertisers, provides the targeting technology, serves the ads, and handles advertiser payment collection. To participate, content providers just sign up online, put a bit of Google-supplied HTML code on their pages, and wait for Google to send them cash (Web sites typically get about seventy to eighty cents for every AdSense dollar that Google collects) (Tedeschi, 2006).

Google originally developed AdSense to target ads based on keywords automatically detected inside the content of a Web site. A blog post on your favorite sports team, for example, might be accompanied by ads from ticket sellers or sports memorabilia vendors. AdSense and similar online ad networks provide advertisers with access to the long tail of niche Web sites by offering both increased opportunities for ad exposure as well as more-refined targeting opportunities.

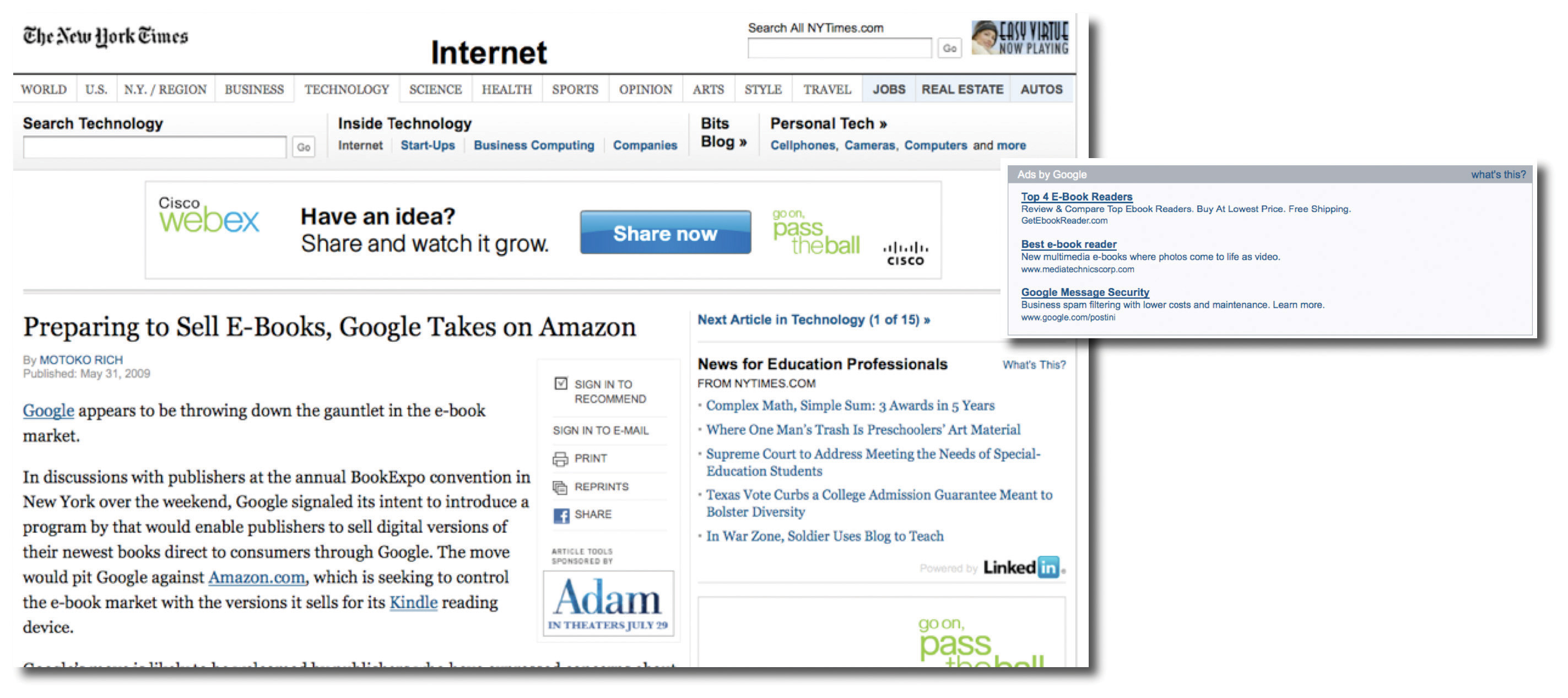

Figure 14.9

The images above show advertising embedded around a story on the New York Times Web site. The page runs several ads provided by different ad networks. For example, the WebEx banner ad above the article’s headline was served by AOL-owned Platform-A/Tacoda. The “Ads by Google” box appeared at the end of the article. Note how the Google ads are related to the content of the Times article.

Running ads on your Web site is by no means a guaranteed path to profits. The Internet graveyard is full of firms that thought they’d be able to sustain their businesses on ads alone. But for many Web sites, ad networks can be like oxygen, sustaining them with revenue opportunities they’d never be able to achieve on their own.

For example, AdSense provided early revenue for the popular social news site Digg, as well as the multimillion-dollar TechCrunch media empire. It supports Disaboom, a site run by physician and quadriplegic Dr. Glen House. And it continues to be the primary revenue generator for AskTheBuilder.com. That site’s founder, former builder Tim Carter, had been writing a handyman’s column syndicated to some thirty newspapers. The newspaper columns didn’t bring in enough to pay the bills, but with AdSense he hit pay dirt, pulling in over $350,000 in ad revenue in just his first year (Rothenberg, 2008)!

Beware the Content Adjacency Problem

Contextual advertising based on keywords is lucrative, but like all technology solutions it has its limitations. Vendors sometimes suffer from content adjacency problems when ads appear alongside text they’d prefer to avoid. In one particularly embarrassing example, a New York Post article detailed a gruesome murder where hacked up body parts were stowed in suitcases. The online version of the article included contextual advertising and was accompanied by…luggage ads (Overholt, 2007).

To combat embarrassment, ad networks provide opportunities for both advertisers and content providers to screen out potentially undesirable pairings based on factors like vendor, Web site, and category. Advertisers can also use negative keywords, which tell networks to avoid showing ads when specific words appear (e.g., setting negative keywords to “murder” or “killer” could have spared luggage advertisers from the embarrassing problem mentioned above). Ad networks also refine ad-placement software based on feedback from prior incidents (for more on content adjacency problems, see Chapter 8 “Facebook: Building a Business from the Social Graph”).

Google launched AdSense in 2003, but Google is by no means the only company to run an ad network, nor was it the first to come up with the idea. Rivals include the Yahoo! Publisher Network, Microsoft’s adCenter, and AOL’s Platform-A. Others, like Quigo, don’t even have a consumer Web site yet manage to consolidate enough advertisers to attract high-traffic content providers such as ESPN, Forbes, Fox, and USA Today. Advertisers also aren’t limited to choosing just one ad network. In fact, many content provider Web sites will serve ads from several ad networks (as well as exclusive space sold by their own sales force), oftentimes mixing several different offerings on the same page.

Ad Networks and Competitive Advantage

While advertisers can use multiple ad networks, there are several key strategic factors driving the industry. For Google, its ad network is a distribution play. The ability to reach more potential customers across more Web sites attracts more advertisers to Google. And content providers (the Web sites that distribute these ads) want there to be as many advertisers as possible in the ad networks that they join, since this should increase the price of advertising, the number of ads served, and the accuracy of user targeting. If advertisers attract content providers, which in turn attract more advertisers, then we’ve just described network effects! More participants bringing in more revenue also help the firm benefit from scale economies—offering a better return on investment from its ad technology and infrastructure. No wonder Google’s been on such a tear—the firm’s loaded with assets for competitive advantage!

Google’s Ad Reach Gets Bigger

While Google has the largest network specializing in distributing text ads, it had been a laggard in graphical display ads (sometimes called image ads). That changed in 2008, with the firm’s $3.1 billion acquisition of display ad network and targeting company DoubleClick. Now in terms of the number of users reached, Google controls both the largest text ad network and the largest display ad network (Baker, 2008).

Key Takeaways

- Google also serves ads through non-Google partner sites that join its ad network. These partners distribute ads for Google in exchange for a percentage of the take.

- AdSense ads are targeted based on keywords that Google detects inside the content of a Web site.

- AdSense and similar online ad networks provide advertisers with access to the long tail of niche Web sites.

- Ad networks handle advertiser recruitment, ad serving, and revenue collection, opening up revenue earning possibilities to even the smallest publishers.

Questions and Exercises

- On a percentage basis, how important is AdSense to Google’s revenues?

- Why do ad networks appeal to advertisers? What do they appeal to content providers? What functions are assumed by the firm overseeing the ad network?

- What factors determine the appeal of an ad network to advertisers and content providers? Which of these factors are potentially sources of competitive advantage?

- Do dominant ad networks enjoy strong network effects? Are there also strong network effects that drive consumers to search? Why or why not?

- How difficult is it for a Web site to join an ad network? What does this imply about ad network switching costs? Does it have to exclusively choose one network over another? Does ad network membership prevent a firm from selling its own online advertising, too?

- What is the content adjacency problem? Why does it occur? What classifications of Web sites might be particularly susceptible to the content adjacency problem? What can advertisers do to minimize the likelihood that a content adjacency problem will occur?

1Google, “Google Announces Fourth Quarter and Fiscal Year 2008 Results,” press release, January 22, 2009.

References

Baker, L., “Google Now Controls 69% of Online Advertising Market,” Search Engine Journal, March 31, 2008.

Overholt, A., “Search for Tomorrow,” Fast Company, December 19, 2007.

Rothenberg, R., “The Internet Runs on Ad Billions,” BusinessWeek, April 10, 2008.

Tedeschi, B., “Google’s Shadow Payroll Is Not Such a Secret Anymore,” New York Times, January 16, 2006.

New York Times Web site. The page runs several ads provided by different ad networks. For example, the WebEx banner ad above the article’s headline was served by AOL-owned Platform-A/Tacoda. The “Ads by Google” box appeared at the end of the article. Note how the Google ads are related to the content of the Times article.” style=”max-width: 497px;”/>

New York Times Web site. The page runs several ads provided by different ad networks. For example, the WebEx banner ad above the article’s headline was served by AOL-owned Platform-A/Tacoda. The “Ads by Google” box appeared at the end of the article. Note how the Google ads are related to the content of the Times article.” style=”max-width: 497px;”/>