Everyday Occupations: The World of Men

The novel Dream of the Red Chamber takes place in a world of women. The plot revolves around Jia Baoyu, but the world he inhabits is a female world. Surely Baoyu’s refusal to grow up and take on the responsibilities of the adult world is connected to the somewhat lackluster portrayal of adult men in the novel.

The bane of Baoyu’s existence is pressure to study and do well on the civil service examinations. Chinese elite status was attained through a series of civil service examinations, which were in theory open to almost all men. Preparation for the examinations entailed long years of arduous study, which meant that it was rare that a man from a poor family was able to participate in the system. There were multiple levels of examination, beginning at the local and ending with the capital. The process could take decades. Studying for the examinations was a full-time job. When a man was studying for the examinations, he was not producing income for his family. This further restricted access to the examination system to men who came from families of means. The success rate varied with time and place, but it was everywhere quite small.

Elite status had to be reproduced every generation: if a family went for even one generation without producing a degree holder, its status would be jeopardized. In the second chapter of the novel, Leng Zixing comments on several problems that foreshadow the fall of the Jia family, but that the most serious problem is that they are not able to turn out good sons, that each generation is worse than the last.

Jia Baoyu is reprimanded by his maid Aroma for his lack of interest in the civil service examinations. He refers to those who do study for the examinations as “career worms.” In the 120 chapter version of the novel, in the final chapter, he does finally take and pass the civil service examinations but then vanishes from the earthly realm.

TEXT FROM CHAPTER 19: AROMA LECTURES BAOYU ABOUT STUDYING

Baoyu’s maid Aroma lectures him about his disrespectful attitude toward studying (and, by implication, to his father) in chapter 19 of the novel. Although Aroma’s status is that of maid, in this particular instance she does not hesitate to speak plainly to Baoyu about the consequences of his “rude remarks” about scholarship.

I don’t care whether you really like studying or not, but even if you don’t I’d like you to at least pretend you do when you’re with your father or any other gentlemen, and not always be making sarcastic remarks about it. If you could only put on an appearance of liking it, he would have less cause to be angry with you and could even take a bit of pride in you when he was talking to his friends. Look at it from his point of view. Every generation of your family up until now have been scholars. Then suddenly you come along. Not only do you hate studying—that’s already enough to make him feel angry and upset—but on top of that you have to be forever making rude remarks about it—and not only behind his back, but even when he’s there. According to you anyone who studies and tries to improve himself is a “career worm.”

Chinese text, from Chinese text project.

你真愛念書也罷,假愛也罷,只在老爺跟前,或在別人跟前,你別只管嘴裡混批,只作出個愛念書的樣兒來,也叫老爺少生點兒氣,在人跟前也好說嘴。老爺心裡想著:我家代代念書,只從有了你,不承望不但不愛念書,--已經他心裡又氣又惱了--而且背前面後混批評。凡讀書上進的人,你就起個外號兒,叫人家『祿蠹』

Baoyu’s contempt for the civil service examination system was extreme, But there were other critics as well. One of the charges against the examination system (which functioned as the major way of recruiting officials for about a thousand years until its abolition in 1905) is that it was stultifying and prone to corruption. (It also created a national elite who had studied the same canonical Confucian texts, and created a context in which bureaucratic leaders were likely to be well-educated men.)

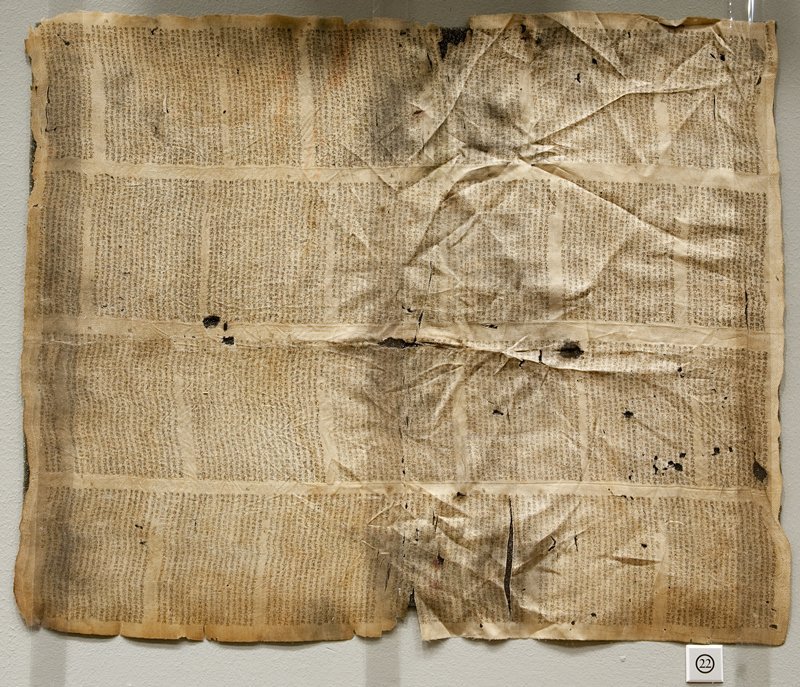

A handkerchief with 10,000 characters on it, texts explicating the Analects of Confucius, held at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. A zoomable reproduction is available here:

The handkerchief pictured above is a civil service examination cheat sheet. Note how worn the handkerchief is. It clearly had done duty in more than one examination hall! Cheating on the civil service exams was pervasive, and candidates would be searched as they entered the examination hall, for texts, for notes, for cheatsheets, and for money with which to bribe the examiners.

In this short video, made as part of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts’ celebration of its hundredth year, Ann Waltner, Karil Kucera and Kathleen Ryor talk about the handkerchief.

This blog from the Cotsen Children’s Collection at Princeton University discusses several “Cribbing Garments” and crib sheets in detail.

More on Civil Service Examinations

The bane of Baoyu’s existence is pressure to study and do well on the civil service examinations. Chinese elite status was attained through a series of civil service examinations, which were in theory open to almost all men. (Some men were excluded: the sons of actors and prostitutes, for example.) Preparation for the examinations entailed long years of arduous study, which meant that it was rare that a man from a poor family was able to participate in the system. There were multiple levels of examination, beginning at the local and ending with the capital. The process could take decades. Studying for the examinations was a full-time job. When a man was studying for the examinations, he was not producing income for his family. This effectively restricted access to the examination system to men who came from families of means. The success rate varied with time and place, but it was everywhere quite small.

Elite status had to be reproduced every generation: if a family went for even one generation without producing a degree holder, its status would be jeopardized. In the second chapter of the novel, Leng Zixing comments on several problems that foreshadow the fall of the Jia family, but that the most serious problem is that they are not able to turn out good sons, that each generation is worse than the last.

As we saw above, Jia Baoyu is reprimanded by his maid Aroma for his lack of interest in the civil service examinations. He refers to those who do study for the examinations as “career worms.” In the 120 chapter version of the novel, in the final chapter, he does finally take and pass the civil service examinations but then vanishes from the earthly realm.

Baoyu’s contempt for the civil service examination system was extreme, But there were other critics as well. One of the charges against the examination system (which functioned as the major way of recruiting officials for about a thousand years until its abolition in 1905) is that it was stultifying and prone to corruption. (It also created a national elite who had studied the same canonical Confucian texts, and created a context in which bureaucratic leaders were likely to be well-educated men.)

Pu Songling was another critic of the examination system.

Pu Songling on Civil Service Exams

Pu Songling (1640–1715), an important writer a generation earlier than Cao Xueqin 曹雪芹, wrote a humorous and scathing critique of the examination system, called “The Seven Likenesses of a Candidate.”

A licentiate taking the provincial examination may be likened to seven things. When entering the examination hall, bare-footed and carrying a basket, he is like a beggar. At roll-call time, being shouted at by officials and abused by their subordinates, he is like a prisoner. When writing in his cell, with his head and feet sticking out of the booth, he is like a cold bee late in autumn. Upon leaving the examination hall, being in a daze and seeing a changed universe, he is like a sick bird out of a cage. When anticipating the results, he is on pins and needles; one moment he fantasizes success and magnificent mansions are instantly built; another moment he fears failure, and his body is reduced to a corpse. At this point, he is like a chimpanzee in captivity. Finally, the messengers come on galloping horses and confirm the absence of his name on the list of successful candidates. His complexion becomes ashen and his body stiffens like a poisoned fly no longer able to move. Disappointed and discouraged, he vilifies the examiners for their blindness and blames the unfairness of the system. Thereupon he collects all his books and papers from his desk and sets them on fire; unsatisfied, he tramples over the ashes; still unsatisfied, he throws the ashes into a filthy gutter. He is determined to abandon the world by going into the mountains, and he is resolved to drive away any person who dares speak to him about examination essays. With the passage of time, his anger subsides and his aspiration rises. Like a turtle dove just hatched, he rebuilds his nest and starts the process once again. (Elman 2000, 361)

Suggestions for further reading: Several translations of Pu Songling’s Liaozhai zhiyi exist. Two good examples are John Minford (Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio, Penguin, 2006) and Denis C. and Victor Mair (Strange Tales from Make-do Studio (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1989.)

An excellent book on the text is Judith T. Zeitlin. Historian of the Strange : Pu Songling and the Chinese Classical Tale. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1993.

Studio of Gratifying Discourse

The photograph to the left is of a room called the “Studio of Gratifying Discourse” which has been reconstructed at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Of course we do not know what Baoyu’s father’s fictional studio might have looked like, but this room provides evidence that allows us to imagine it. This link will lead you to a zoomable photograph of the room.

The photograph to the left is of a room called the “Studio of Gratifying Discourse” which has been reconstructed at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Of course we do not know what Baoyu’s father’s fictional studio might have looked like, but this room provides evidence that allows us to imagine it. This link will lead you to a zoomable photograph of the room.

The room, a scholar’s studio, is set up with the accoutrements of a male scholarly life–books, paintings, brushes, inkstones.

In this short video Ann Waltner, Karil Kucera, and Kathleen Ryor talk about the scholar’s studio and its implications for Dream of the Red Chamber.

In this slightly longer video, Waltner, Kucera, and Ryor talk in more detail about the same room.