13.3 The Internet’s Effects on Media Economies

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the ways synergy is used on the Internet.

- Summarize the purpose and impact of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

The challenge to media economics is one of production. When print media was the only widely available media, the concept was simple: Sell newspapers, magazines, and books. Sales of these goods could be gauged like any other product, although in media’s case, the good was intangible—information—rather than the physical paper and ink. The transition from physical media to broadcast media presented a new challenge, because consumers did not pay money for radio and, later, television programming; instead, the price was an interruption every so often by a “word from our sponsors.” However, even this practice hearkened back to the world of print media; just as newspapers and magazines sell advertising space, radio and television networks sell space on their airwaves.

The fundamental shift in Internet economics has been the miniscule price of online space compared to that in print or broadcast media. Combined with the instantaneous proliferation of information, the Internet seems to pose a grave threat to traditional media. Media outlets have responded by establishing themselves online, and it is now practically unheard of for any media company to lack an Internet presence. Companies’ archives have opened up, and aside from a few holdouts such as The Wall Street Journal, nearly every newspaper allows free online access, although some papers, like The New York Times, are going to experiment with a paid subscription model to solve the problem of dwindling revenues. Newspapers now offer video content online, and radio and television networks have published traditional text-and-photo stories. Through Internet portals, media companies have synergized their content; they are no longer merely television networks or local newspapers but instead are quickly moving to become a little bit of everything.

Online Synergy

Although the Internet has had many effects on media economics, ranging from media piracy to the lowered costs of distribution, arguably the greatest effect has been the synergy of different forms of media. For example, the front page of The New York Times website contains multiple short video clips, and the front page of Fox News’ website contains clips from the cable television network along with relevant articles written by FoxNews.com staff. Media outlets offer many of these services for free to consumers, if for no other reason than because consumers have become accustomed to getting this content for free elsewhere on the Internet.

The Internet has also drastically changed the way that companies’ advertising models operate. During the early years of the Internet, many web ads were geared toward sites such as Amazon and eBay, where consumers purchased products or services. Today, however, many ads—particularly on sites for high-profile media outlets such as Fox News and The New York Times—are for products that are not typically bought online, such as cars or major credit cards. However, another category of advertising that is tailored toward individual web pages has also gained prominence on the Internet. In this form of advertising, marketers match advertisers with particular keywords on particular web pages. For example, if the page is a how-to guide for fixing a refrigerator, some of the targeted ads might be for local refrigerator repair shops.

Internet by Google

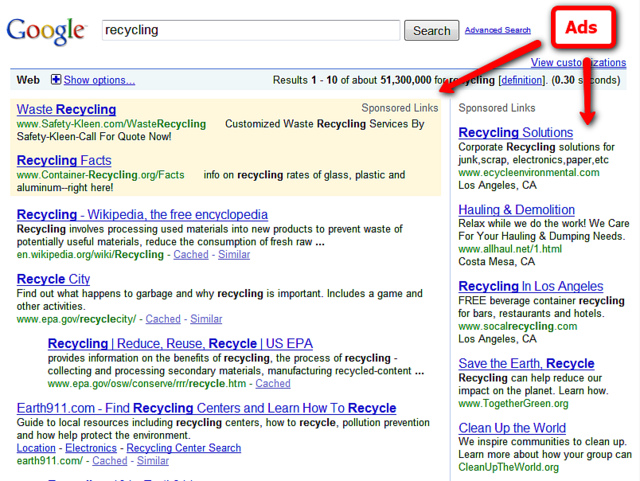

Figure 13.3

Google makes almost all of its money through advertising, allowing it to provide many services such as e-mail and document sharing for free.

search-engine-land – Google Ads – CC BY 2.0.

Search-engine company Google has been working to perfect this type of targeted advertising search. Low-cost text ads may appear next to its search results, on various web pages, and in the sidebar of its free web-based e-mail service, Gmail. More than just using algorithms to sort through massive amounts of data and matching advertising to content, Google has lowered the cost barrier to advertising, as well as the volume barrier to hosting advertising. Because Google automatically matches sites with advertisers, an independent site can sign up for its advertising service and get paid for each person who follows the text links. Likewise, relatively small companies can buy advertising space in specialized niches without having to go through a large-volume ad buyer. This business has proven extremely productive; the bulk of Google’s revenue comes from advertising even as it gives away services such as e-mail and document sharing.

Problems of Digital Delivery

Search engines like Google and video-sharing sites like YouTube (which is owned by Google) allow access to online information, but they do not actually produce that information themselves. Thus, the propensity of these sites to gather information and then make it available to consumers free of charge does not necessarily sit well with those who financially depend on the sale of this information.

Google News

One of Google’s more controversial projects is Google News, a news aggregator that automatically collects news stories from various sources on the Internet. This service allows users to view the latest news from many different sources conveniently in one location. However, the project has been met with opposition from a number of those news sources, who contend that Google has infringed on their copyrights and cost them revenue. The Wall Street Journal has been one of the more vocal critics of Google News. In April 2009, editor Robert Thomson said that news aggregators are “best described as parasites (Schulze, 2009).” In December 2009, Google responded to these complaints by allowing publishers to set a limit on the number of articles per day a reader can view for free through Google.

Music and File Sharing

The recent confrontation between Google and the traditional news media is only one of many problems resulting from digital technology. Digital technology can create exact copies of data so that one copy cannot be distinguished from the other. In other words, although a printed book might be nicer than a photocopy of that book, a digitization of the book is exactly the same as all other digitized copies and can be transmitted almost instantly. Similarly, although cassette tape copies of recorded music offered lower sound fidelity than the originals, the emergence of writable CD technology during the 1990s allowed for the creation of a copy of a digital audio CD that was identical to the original.

As data storage and transmission costs dropped, CDs no longer had to be physically copied to other CDs. With the advent of MP3 digital encoding, the music information on a CD could be compressed into a relatively small, portable format that could be transmitted easily over the Internet, and music file sharing took off. Although these recordings were not exactly the same as their CD-quality counterparts, most listeners could not tell the difference—or they just didn’t care, because they were now able to share music files conveniently and for free. The practice of transmitting music over the Internet through services such as Napster quickly ballooned.

Video Streaming

As high-bandwidth Internet connections proliferated, video-sharing and streaming sites such as YouTube started up. Although these sites were supposedly intended for users to upload and share their own amateur videos, one of the big draws of the site was the high quantity of television show episodes, music videos, and other commercial content that has been posted illegally. The replication potential inherent in digital technology combined with online transmission has caused a sea change in media industries that rely on income directly from consumers, such as books and recorded music. However, as the next section will show, the shift of media and information to the Internet can pose the risk of a digital divide, where those without Internet access are at an even greater disadvantage than they were before.

Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)

Producers of content are not without protection under the law. In 1998, Congress enacted the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) in an effort to stop the illegal copying and distribution of copyrighted material. The legislation defined many digital gray areas that previously may not have been explicitly covered, such as circumventing antipiracy measures in commercial software; requiring webcasters to pay licensing fees to record companies; and exempting libraries, archives, and some other nonprofit institutions from some of these rules under certain circumstances. Since 1998, this legislation has been the bedrock of a variety of claims against sites such as YouTube. Under the law, copyright holders may send letters to Internet hosts distributing their copyrighted material. Certifying that they have a good-faith belief that the host does not have prior permission to distribute the content, copyright holders may request a removal of that material from the site (U.S. Copyright Office, 1998).

Although much of the law has to do with the rights of copyright holders to request the removal of their works from unlicensed sites, much of the DMCA also enacts protections for Internet service providers (ISPs). Although before there had been some question as to whether ISPs could be charged with copyright infringement merely for allowing reproducers to use their bandwidth, the DMCA made it clear that ISPs are not expected to police their own bandwidth for illegal use and are therefore not liable. Although the DMCA is not necessarily to everyone’s liking—requiring individual takedown notices is time-consuming for corporations, and the relative lack of safeguards can allow large companies to bully ISPs into shutting down smaller sites, given a good-faith notice—the protections and clarifications that it has created have cleared up some of the confusion surrounding digital media (Vance, 2003). However, as the price of bandwidth drastically drops and as more media goes digital, copyright laws will inevitably need to be amended again.

Key Takeaways

- The Internet has allowed media companies to synergize their content, broadcasting the same ideas and products across multiple platforms. This significantly helps with reducing relative first copy costs because the Internet’s marginal costs are minimal.

- The DMCA exempts Internet service providers from liability in policing their own services for illegal downloads. However, it also enacts copyright protection for digital media, thereby allowing copyright holders to send takedown notices. As long as they profess a good-faith belief that the works were not used with permission, the recipient is generally required to take them down.

Exercises

Navigate to a traditional media outlet’s online portal, such as NYTtimes.com or FoxNews.com. Print out a hard copy of the home page and write on it, or save it to your computer and open it in a document editor such as Microsoft Word to annotate it. Note items such as these:

- Are there any media formats on the page aside from the outlet’s normal ones? Why might this traditional media outlet choose to produce different media formats on the Internet?

- Does the media outlet promote its other products? If so, how? How does the Internet enable this type of synergy?

- What types of personalization options are there? Does social networking show any influence?

- Under the DMCA, what recourse would this media outlet have if its copyrighted content were being hosted elsewhere without its permission?

References

Schulze, Jane. “Google Dubbed Internet Parasite by WSJ Editor,” Australian (Sydney), April 6, 2009, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/media/google-dubbed-internet-parasite/story-e6frg996-1225696931547.

U.S. Copyright Office, “Copyright Law: Chapter 5,” 1998, http://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap5.html.

Vance, Ashlee. “Court Confirms DMCA ‘Good Faith’ Web Site Shut Down Rights,” Register, May 30, 2003, http://www.theregister.co.uk/2003/05/30/court_confirms_dmca_good_faith/.