1.5 The Role of Social Values in Communication

Learning Objectives

- Identify two limitations on free speech that are based on social values.

- Identify examples of propaganda in mass media.

- Explain the role of the gatekeeper in mass media.

In a 1995 Wired magazine article, “The Age of Paine,” Jon Katz suggested that the Revolutionary War patriot Thomas Paine should be considered “the moral father of the Internet.” The Internet, Katz wrote, “offers what Paine and his revolutionary colleagues hoped for—a vast, diverse, passionate, global means of transmitting ideas and opening minds.” In fact, according to Katz, the emerging Internet era is closer in spirit to the 18th-century media world than to the 20th-century’s “old media” (radio, television, print). “The ferociously spirited press of the late 1700s…was dominated by individuals expressing their opinions. The idea that ordinary citizens with no special resources, expertise, or political power—like Paine himself—could sound off, reach wide audiences, even spark revolutions, was brand-new to the world (Creel, 1920).” Katz’s impassioned defense of Paine’s plucky independence speaks to the way social values and communication technologies are affecting our adoption of media technologies today. Keeping Katz’s words in mind, we can ask ourselves additional questions about the role of social values in communication. How do they shape our ideas of mass communication? How, in turn, does mass communication change our understanding of what our society values?

Figure 1.8

Thomas Paine is regarded by some as the “moral father of the Internet” because his independent spirit is reflected in the democratization of mass communication via the Internet.

Marion Doss – Thomas Paine, Engraving – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Free Speech and Its Limitations

The value of free speech is central to American mass communication and has been since the nation’s revolutionary founding. The U.S. Constitution’s very first amendment guarantees the freedom of the press. Because of the First Amendment and subsequent statutes, the United States has some of the broadest protections on speech of any industrialized nation. However, there are limits to what kinds of speech are legally protected—limits that have changed over time, reflecting shifts in U.S. social values.

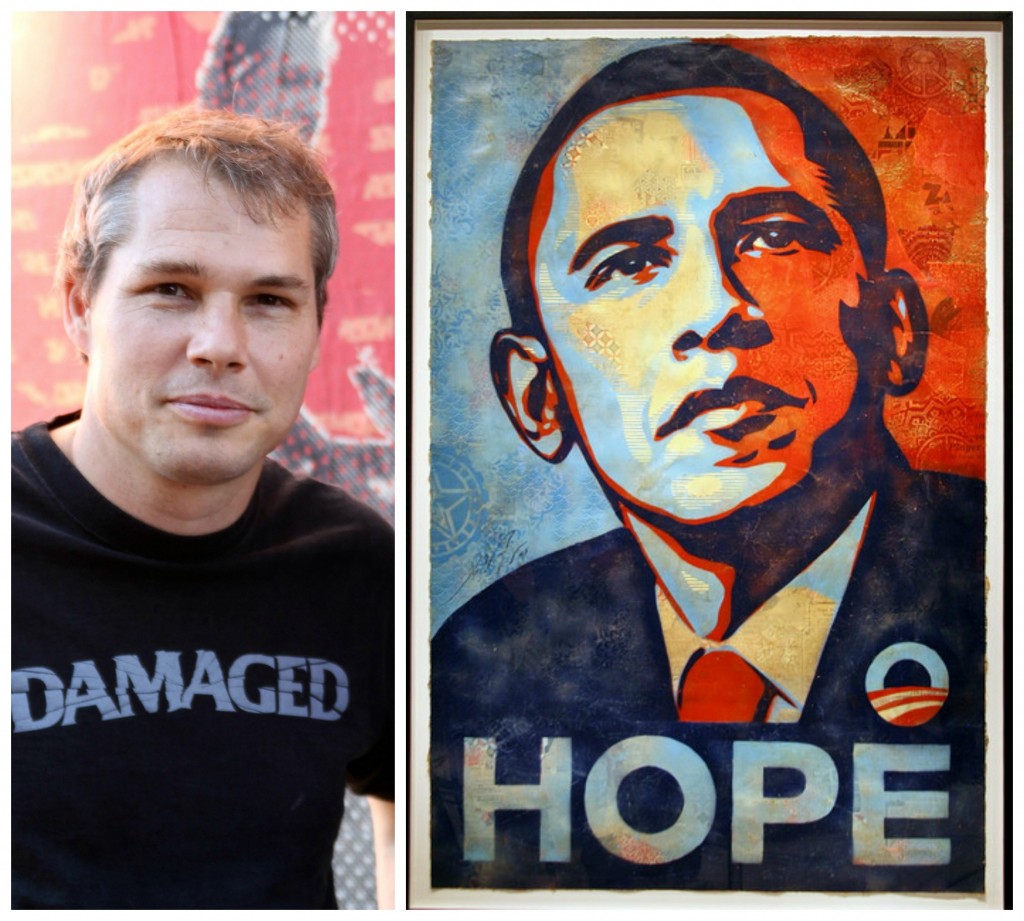

Figure 1.9

Artist Shepard Fairey, creator of the iconic Obama HOPE image, was sued by the Associated Press for copyright infringement; Fairey argued that his work was protected by the fair use exception.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain; Cliff – National Portrait Gallery Hangs Shepard Fairey’s Portrait of Barack Obama – CC BY 2.0.

Definitions of obscenity, which is not protected by the First Amendment, have altered with the nation’s changing social attitudes. James Joyce’s Ulysses, ranked by the Modern Library as the best English-language novel of the 20th century, was illegal to publish in the United States between 1922 and 1934 because the U.S. Customs Court declared the book obscene because of its sexual content. The 1954 Supreme Court case Roth v. the United States defined obscenity more narrowly, allowing for differences depending on community standards. The sexual revolution and social changes of the 1960s made it even more difficult to pin down just what was meant by community standards—a question that is still under debate to this day. The mainstreaming of sexually explicit content like Playboy magazine, which is available in nearly every U.S. airport, is another indication that obscenity is still open to interpretation.

Regulations related to obscene content are not the only restrictions on First Amendment rights; copyright law also puts limits on free speech. Intellectual property law was originally intended to protect just that—the proprietary rights, both economic and intellectual, of the originator of a creative work. Works under copyright can’t be reproduced without the authorization of the creator, nor can anyone else use them to make a profit. Inventions, novels, musical tunes, and even phrases are all covered by copyright law. The first copyright statute in the United States set 14 years as the maximum term for copyright protection. This number has risen exponentially in the 20th century; some works are now copyright-protected for up to 120 years. In recent years, an Internet culture that enables file sharing, musical mash-ups, and YouTube video parodies has raised questions about the fair use exception to copyright law. The exact line between what types of expressions are protected or prohibited by law are still being set by courts, and as the changing values of the U.S. public evolve, copyright law—like obscenity law—will continue to change as well.

Propaganda and Other Ulterior Motives

Sometimes social values enter mass media messages in a more overt way. Producers of media content may have vested interests in particular social goals, which, in turn, may cause them to promote or refute particular viewpoints. In its most heavy-handed form, this type of media influence can become propaganda, communication that intentionally attempts to persuade its audience for ideological, political, or commercial purposes. Propaganda often (but not always) distorts the truth, selectively presents facts, or uses emotional appeals. During wartime, propaganda often includes caricatures of the enemy. Even in peacetime, however, propaganda is frequent. Political campaign commercials in which one candidate openly criticizes the other are common around election time, and some negative ads deliberately twist the truth or present outright falsehoods to attack an opposing candidate.

Other types of influence are less blatant or sinister. Advertisers want viewers to buy their products; some news sources, such as Fox News or The Huffington Post, have an explicit political slant. Still, people who want to exert media influence often use the tricks and techniques of propaganda. During World War I, the U.S. government created the Creel Commission as a sort of public relations firm for the United States’ entry into the war. The Creel Commission used radio, movies, posters, and in-person speakers to present a positive slant on the U.S. war effort and to demonize the opposing Germans. Chairman George Creel acknowledged the commission’s attempt to influence the public but shied away from calling their work propaganda:

In no degree was the Committee an agency of censorship, a machinery of concealment or repression…. In all things, from first to last, without halt or change, it was a plain publicity proposition, a vast enterprise in salesmanship, the world’s greatest adventures in advertising…. We did not call it propaganda, for that word, in German hands, had come to be associated with deceit and corruption. Our effort was educational and informative throughout, for we had such confidence in our case as to feel that no other argument was needed than the simple, straightforward presentation of the facts (Creel, 1920).

Of course, the line between the selective (but “straightforward”) presentation of the truth and the manipulation of propaganda is not an obvious or distinct one. (Another of the Creel Commission’s members was later deemed the father of public relations and authored a book titled Propaganda.) In general, however, public relations is open about presenting one side of the truth, while propaganda seeks to invent a new truth.

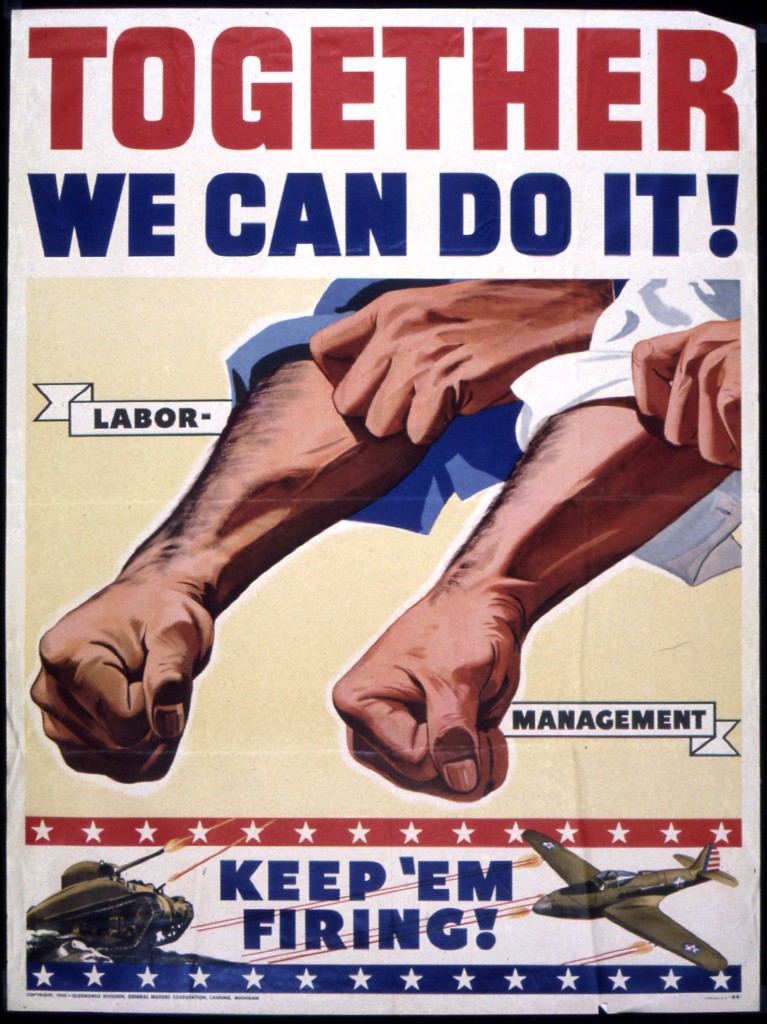

Figure 1.10

World War I propaganda posters were sometimes styled to resemble movie posters in an attempt to glamorize the war effort.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Gatekeepers

In 1960, journalist A. J. Liebling wryly observed that “freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” Liebling was referring to the role of gatekeepers in the media industry, another way in which social values influence mass communication. Gatekeepers are the people who help determine which stories make it to the public, including reporters who decide what sources to use and editors who decide what gets reported on and which stories make it to the front page. Media gatekeepers are part of society and thus are saddled with their own cultural biases, whether consciously or unconsciously. In deciding what counts as newsworthy, entertaining, or relevant, gatekeepers pass on their own values to the wider public. In contrast, stories deemed unimportant or uninteresting to consumers can linger forgotten in the back pages of the newspaper—or never get covered at all.

In one striking example of the power of gatekeeping, journalist Allan Thompson lays blame on the news media for its sluggishness in covering the Rwandan genocide in 1994. According to Thompson, there weren’t many outside reporters in Rwanda at the height of the genocide, so the world wasn’t forced to confront the atrocities happening there. Instead, the nightly news in the United States was preoccupied by the O. J. Simpson trial, Tonya Harding’s attack on a fellow figure skater, and the less bloody conflict in Bosnia (where more reporters were stationed). Thompson went on to argue that the lack of international media attention allowed politicians to remain complacent (Thompson, 2007). With little media coverage, there was little outrage about the Rwandan atrocities, which contributed to a lack of political will to invest time and troops in a faraway conflict. Richard Dowden, Africa editor for the British newspaper The Independent during the Rwandan genocide, bluntly explained the news media’s larger reluctance to focus on African issues: “Africa was simply not important. It didn’t sell newspapers. Newspapers have to make profits. So it wasn’t important (Thompson, 2007).” Bias on the individual and institutional level downplayed the genocide at a time of great crisis and potentially contributed to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

Gatekeepers had an especially strong influence in old media, in which space and time were limited. A news broadcast could only last for its allotted half hour, while a newspaper had a set number of pages to print. The Internet, in contrast, theoretically has room for infinite news reports. The interactive nature of the medium also minimizes the gatekeeper function of the media by allowing media consumers to have a voice as well. News aggregators like Digg allow readers to decide what makes it on to the front page. That’s not to say that the wisdom of the crowd is always wise—recent top stories on Digg have featured headlines like “Top 5 Hot Girls Playing Video Games” and “The girl who must eat every 15 minutes to stay alive.” Media expert Mark Glaser noted that the digital age hasn’t eliminated gatekeepers; it’s just shifted who they are: “the editors who pick featured artists and apps at the Apple iTunes store, who choose videos to spotlight on YouTube, and who highlight Suggested Users on Twitter,” among others (Glaser, 2009). And unlike traditional media, these new gatekeepers rarely have public bylines, making it difficult to figure out who makes such decisions and on what basis they are made.

Observing how distinct cultures and subcultures present the same story can be indicative of those cultures’ various social values. Another way to look critically at today’s media messages is to examine how the media has functioned in the world and in the United States during different cultural periods.

Key Takeaways

- American culture puts a high value on free speech; however, other societal values sometimes take precedence. Shifting ideas about what constitutes obscenity, a kind of speech that is not legally protected by the First Amendment, is a good example of how cultural values impact mass communication—and of how those values change over time. Copyright law, another restriction put on free speech, has had a similar evolution over the nation’s history.

- Propaganda is a type of communication that attempts to persuade the audience for ideological, political, or social purposes. Some propaganda is obvious, explicit, and manipulative; however, public relations professionals borrow many techniques from propaganda and they try to influence their audience.

- Gatekeepers influence culture by deciding which stories are considered newsworthy. Gatekeepers can promote social values either consciously or subconsciously. The digital age has lessened the power of gatekeepers somewhat, as the Internet allows for nearly unlimited space to cover any number of events and stories; furthermore, a new gatekeeper class has emerged on the Internet as well.

Exercises

Please answer the following questions. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Find an advertisement—either in print, broadcast, or online—that you have recently found to be memorable. Now find a nonadvertisement media message. Compare the ways that the ad and the nonad express social values. Are the social values the same for each of them? Is the influence overt or covert? Why did the message’s creators choose to present their message in this way? Can this be considered propaganda?

- Go to a popular website that uses user-uploaded content (YouTube, Flickr, Twitter, Metafilter, etc.). Look at the content on the site’s home page. Can you tell how this particular content was selected to be featured? Does the website list a policy for featured content? What factors do you think go into the selection process?

- Think of two recent examples where free speech was limited because of social values. Who were the gatekeepers in these situations? What effect did these limitations have on media coverage?

References

Creel, George.How We Advertised America (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1920).

Glaser, Marc. “New Gatekeepers Twitter, Apple, YouTube Need Transparency in Editorial Picks,” PBS Mediashift, March 26, 2009, http://www.pbs.org/mediashift/2009/03/new-gatekeepers-twitter-apple-youtube-need-transparency-in-editorial-picks085.html.

Thompson, Allan. “The Media and the Rwanda Genocide” (lecture, Crisis States Research Centre and POLIS at the London School of Economics, January 17, 2007), http://www2.lse.ac.uk/publicEvents/pdf/20070117_PolisRwanda.pdf.