Zhou Qi 周綺

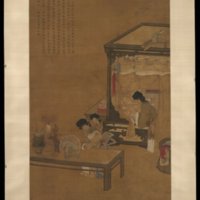

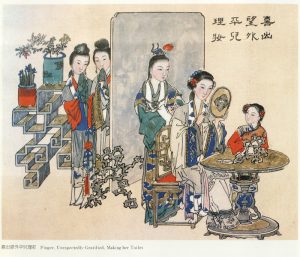

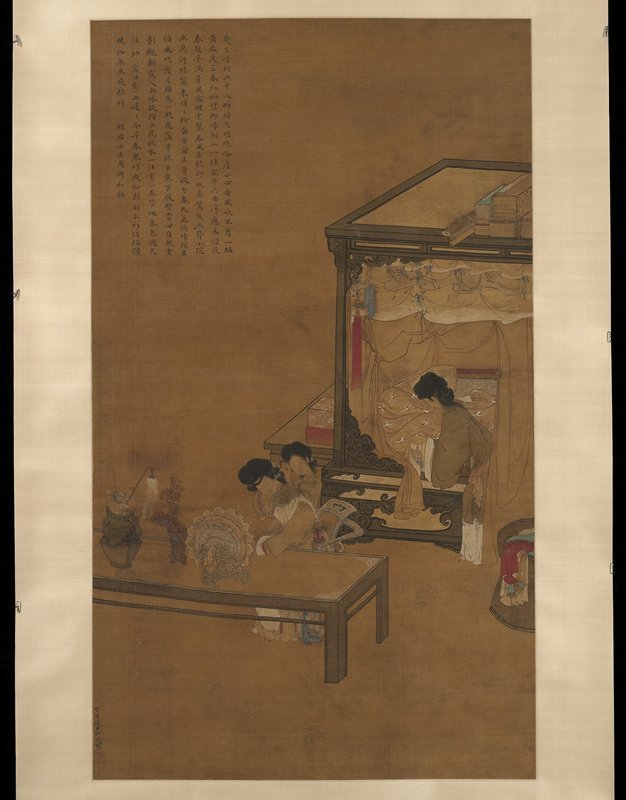

If one wonders how a young woman responded to Dream of the Red Chamber in the early nineteenth century, one need look no further than Zhou Qi 周綺 (1814-1861). The painting to the left, by Wang Qiao 汪乔 and dated 1654, bears a colophon by Zhou Qi 周綺, in which she addresses the courtesans in the painting. I discuss the colophon later in this segment.

If one wonders how a young woman responded to Dream of the Red Chamber in the early nineteenth century, one need look no further than Zhou Qi 周綺 (1814-1861). The painting to the left, by Wang Qiao 汪乔 and dated 1654, bears a colophon by Zhou Qi 周綺, in which she addresses the courtesans in the painting. I discuss the colophon later in this segment.

Zhou Qi 周綺 wrote a brief essay describing her first reading of Dream of the Red Chamber. The essay describes how she casually encountered a copy of the novel on her husband’s desk. Zhou Qi’s 周綺 husband was Wang Xilian 王希廉 (1805-1877) , well-known as a commentator to Dream of the Red Chamber. She writes about the novel that “It takes human feelings and social relations and locates them in the world of powder and rouge, the world of women…Among the book’s emotional events, many are, of course, fully realized, but there are still some which are not fully realized.” She was thus inspired to write ten poems on female characters; the poems were published in 1832, when she would have been eighteen by western reckoning, and no more than 20 by Chinese reckoning. In the phrase “there are still some [events] whose implications have yet to be exhausted,” Zhou 周 suggests why the novel has appealed to commentators, authors, and dramatists for centuries. These unresolved events have prompted commentary and sequels. After composing the poems, Zhou Qi 周綺 is exhausted and takes a nap. A gentleman in old-fashioned dress appears to her in a dream and reprimands her for writing poems on Dream of the Red Chamber. She quotes Confucius (in her dream, no less) to defend the propriety of writing poems which deal with matters of emotion.

The poems Zhou Qi 周綺 has written to resolve events that are important to her focus on female characters, often depicting them at moments of crisis. For example, the poem “Daiyu Burns her Poems,” imagines the moment shortly before Lin Daiyu’s 林黛玉 death when she destroys her poems. “Pretty Patience is Beaten and Keeps her Feelings in Check” shows us Patience (Ping’er 平兒) , the maid of Wang Xifeng王熙鳳 , after she has suffered a painful and humiliating beating. Other poems are about Grandmother Jia’s 賈母 maid Faithful (Yuanyang 鴛鴦) who kills herself shortly after the death of Granny Jia and the maid Skybright (Qingwen晴雯 ) whom Baoyu 寶玉 believes became a hibiscus spirit after her death.

Three of her poems are contained in the set of illustrations of characters in the novel done by the artist Gai Qi 改琦, which was published after his death as the Honglou meng tuyong. Ten of the poems are published in the prefatory matter to Zhou Qi’s husband’s critical edition of the novel, which was first published in 1832.

Zhou Qi 周綺 is also the author of a colophon on a painting by the seventeenth-century painter Wang Qiao, “A Woman at her Dressing Table,” which is held by the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. The Minneapolis Institute of Arts has a zoomable photograph of the image on their website. If you read Chinese, look carefully at the bottom of the colophon. You will find the words 初稿 chu gao, which literally mean “first draft.” The painting was about 150 years old when Zhou Qi 周綺 inscribed the colophon on it; she was clearly not using it for calligraphy practice. It is likely that the phrase is a polite deprecatory phrase, to discount the labor and the skill that went into the making of the colophon. We should not over-read this; deprecatories were commonly used by both men and women in Qing China. We’ll be talking in more detail about the colophon and the painting at the end of the section on Zhou Qi 周綺 .

We do not know very much about Zhou Qi 周綺 aside from her poetry, but what we know is intriguing. She was the posthumous daughter of a man named Wang. She was adopted by her mother’s elder brother, who was surnamed Zhou, and took his surname. Some sources say that she was was married to Wang Xilian as a concubine rather than as a principal wife. The Jiangsu yiwen zhi 江苏艺文志 reports that Wang Xilian married the talented woman (才媛 Zhou Qi as a concubine. The word the text uses for concubine is fushi 副室. (Jiangsu yiwen zhi, 1290). But Hu Wenbin argues that she was in fact not a concubine, but was Wang’s primary wife. (Hu Wenbin. 234). According to materials recently obtained by the Changshu library, which contain prefaces to Zhou Qi’s work both by her and by Wang Xilian, she had three children–a daughter who died as a child, and a son who did not survive a full year. One daughter, Ruoshi, did live to adulthood. But she died in childbirth.

Zhou Qi also had a reputation for great filial piety. In addition to her artistic pursuits, she had some medical knowledge. Her medical knowledge and her filial piety led her to cut her own flesh to make medicine for her mother. (Cutting flesh from one’s own body, usually a thigh, was an act of supreme filial piety.) She may have had some connections to the circle of talented women who surrounded the poet Yuan Mei. (Widmer, Beauty and the Book, 148; Yisu, 274-75.)

Let’s move now to Zhou Qi’s 周綺 poems themselves. Ellen Widmer has translated some of the poems; my students and I have translated some others. I have included notes on translation at the bottom of most pages, which may be of interest to some (but not all) readers.

Zhou Qi 周綺 on her First Experience of Reading the Novel

Zhou Qi 周綺 , the author of the eleven poems which follow, describes how she first encountered the novel. Note the way she describes her first encounter with the novel: it was lying on her husband’s desk, and she casually picked it up. Her husband, Wang Xilian 王希廉 who was also known as Xuexiang 雪香, published an important critical edition of the novel in 1832, and included this text and ten of the poems which follow.

I happened to be beset by petty illnesses and was sitting lonely in our small tower with time on my hands. At the time my husband Xuexiang’s critical edition of Dream of the Red Chamber was sitting on his desk. I read through several chapters and could not help being moved to laughter. It takes human feelings and social relations and locates them in the world of of powder and rouge, the world of women. Compared to books like Shui Hu 水滸 and Xixiang 西厢, it was much more moving. Had Cao Xueqin 曹雪芹 known about my husband, he would have regarded him as a like-minded friend. Among the book’s emotional events, many are, of course, fully realized, but there are still some which are not fully realized. I playfully composed ten poems to expand on their meanings. This is like adding feet to a snake, but I don’t think I have turned truth into falsehood.

When I finished these poems, my spirit was tired and I felt empty inside. Taking time out for a nap, I saw a person wearing old-fashioned clothes and hat, who bowed to me and said, “You are a woman. Writing poetry about the moon and the wind goes against everything your nanny taught you, all the more when you write poems on Dream of the Red Chamber. Aren’t you afraid we will make fun of you?” I answered them saying, “Your point is well taken, but ‘happiness without licentiousness’ and ‘sorrow without harm’ mark the beginning for the ‘Guo feng’ 國風 section of the Classic of Poetry 詩經。 If you insist on suspecting these poems of impropriety, compare them with despicable actions covered up by refined speech. Isn’t the difference between true and false speech as great as the difference between Heaven and Earth?” I hadn’t finished speaking when the person suddenly disappeared and I awoke from my dream. I only smelled cassia fragrance through the curtains, and heard wutong leaves blowing in the wind. Only the quiet moon atop the tower glanced down at my painted eyebrows.

余偶沾微恙,寂坐小楼,竟无消遣计。适案头有雪香夫子所评《红楼梦》书, 试翻数卷,不禁失笑。盖将人情世态,寓于粉迹脂痕。较诸《水浒》、《西厢》尤为痛快。使雪芹有知,当亦引为同心也。然个中情事,淋漓尽致者固多,而未尽然 者,亦复不少。戏拟十律,再广其意。虽画蛇添足,而亦未尝以假失真。诗甫脱稿,神倦肠枯。假寐间见一古衣冠者,揖余而言曰:”子,一闺秀也。弄月吟风,已 乖姆教,而况更作《红楼梦》诗乎?岂不惧吾辈贻讥哉!”即应之曰:”君之言诚是,。然乐而不淫, 哀而不伤,为国风之始。如必以此诗为瓜李之嫌,较之言具彬彬而行仍昧昧, 奚啻相悬天壤耶?”言未竟,人忽不见,吾梦亦醒。但闻桂香入幕,梧叶飘风,楼头澹月,撩人眉黛而已。

Notes on the text

We chose to translate the phrase 粉迹脂痕 which literally means “powder traces and rouge streaks” as “world of powder and rouge” and add the phrase, “the world of women,” to clarify for English readers that the phrase means “world of women.”

The word qing 情 occurs twice in this passage; it is somewhat problematic to translate. It means passion, emotion, but it also means situation. The phrase “human feelings” is a translation of renqing 人情 and the phrase “emotional events” is a translation of qingshi 情事. The phrase translated as “impropriety” is guali zhi xian 瓜李之嫌, which literally means the suspicion about melons and plums, which is derived from a proverb about suspicion about activities that happen in melon fields and under plum trees.

“Adding feet to a snake” is a conventional metaphor for adding to something which is already complete.

The phrases “happiness without licentiousness” and “sorrow without harm” come from the way Confucius characterizes the first poem in the “Guo Feng” section of the Classic of Poetry.《论语·八佾》《关雎》乐而不淫,哀而不伤.” Thus Zhou Qi, asleep and dreaming, calls upon Confucius to defend herself against charges of impropriety by a gentleman in old-fashioned garb. The wutong 梧桐 tree is a symbol of lovers: the name is a homophone meaning “we together.” The wood for the wutong tree (Firmiana simplex or Chinese parasol tree) is also used to make the qin 琴 and other musical instruments because it is particularly resonant. Zhou Qi was also a qin player. and her

Translation slightly modified from Widmer, Beauty and the Book, 150.

And here are translations of some of Zhou Qi’s

周綺 poems:

Zhou Qi 周綺: “Pretty Patience, Beaten, Keeps her Feelings in Check”俏平兒被打含情

In the end, you did not cry out to heaven, nor did you bare your breast.

You swallowed an endless stream of tears; your grievances piled up one after another.

Fine flowers, caught by the wind; there was no cause for jealousy.

Lazy Grasses, common in springtime; one can’t help running into them.

It was a light reproach, truly not a matter of everlasting bitterness.

You do not speak because you in fact have clear understanding.

I envy that your clarity comes from the bottom of your heart.

You could have imitated your mistress, but instead you repaired your makeup.

Translated by Ann Waltner’s reading group: Jiang Yuanxin, Eric Becklin, Zhu Tianxiao, Rachel Kronick, Lars Christensen, and Li Kan.

俏平兒被打含情

究未呼天剖素胸, 淚纷纷咽屈重重。

好花風總憑空妒, 閑草春多不意逢。

薄責原非長恨事, 無言确是有清鍾.

羡卿心底分明甚, 要學夫人却易容。

|

|

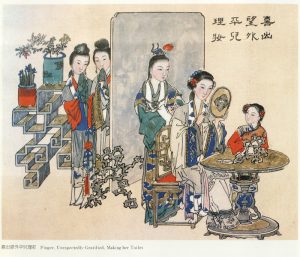

| These two illustrations are Yangliuqing 杨柳青prints. At first glance they may seem almost identical, except for the coloring. (Since Yangliuqing prints were hand-colored, those differences are not surprising.) But note the presence of the small maid at the far right of the dressing table in the second print. This suggests that compositions were revised and recycled. |

Patience (Ping’er 平兒) is the maid of Wang Xifeng王熙鳳. In the scene leading up to the episode referred to in the poem, Wang Xifeng 王熙鳳 has walked in on her husband and another woman, known to us only as Bao Er’s 鲍二 wife. An ugly scene follows, and both Xifeng 熙鳳 and her husband Jia Lian賈璉 strike Patience, who in addition to being Xifeng’s 熙鳳 loyal maid is Lian’s 璉 sexual partner. Patience 平儿 flees, and encounters Baoyu 寶玉. Baoyu 寶玉 sees that she is in disarray, offers her a gown belonging to his maid Aroma (Xiren襲人) and irons her dress and washes her handkerchief. Baoyu 寶玉 reminds Patience 平儿 that it is Xifeng’s 熙鳳 birthday—indeed, Xifeng 王熙鳳 has consumed copious amounts of alcohol in the course of the celebration, which doubtless contributed to the violence against Patience 平儿. The iconic representation of Patience 平儿 is of her sitting at a dressing table, repairing her makeup. A Qing viewer of the image would have known the context, that Patience 平儿 is repairing the damage done by domestic violence.

Zhou Qi’s 周綺 poem talks about Patience’s 平儿 silence in the face of her beating; she does not cry out, she does not bare her breast. The poet tells us that the incident is trivial, but that it reminded Patience of the precariousness of her situation, as a servant, located in between a powerful, tyrannical, and corrupt mistress and a lascivious master who took sexual advantage of her. The modern reader may wonder if the precariousness of Patience’s situation struck a particular chord with Zhou Qi 周綺, herself a concubine.

Notes on the poem

We have not settled on a perfect title yet: we have yet to find a good translation for hanqing 含情. We toyed with the idea of “swallows her rage,” but decided that did not convey the original meaning, which describes a situation where a person is full of passion but is very restrained in the expression of that passion. We then toyed with the idea “keeps her counsel” which conveys Patience’s prudence but not her passion. Another choice we rejected was “holds her peace”–we like the use of swallow or hold for han, whose root meaning is to hold in the mouth, We are open to further suggestions.

In the second line there are two reduplicatives: fenfen 纷纷 and chongchong 重重. Reduplicates in Chinese pose a particular problem to the translator–reduplicatives are much more common in formal Chinese than they are in formal English. We translated fenfen “endless stream” and chongchong “one after another.” We could have been more literal and said “you swallowed your tears drop by drop,” but that may give a sense of few tears, and I think the Chinese has a sense of many tears.

In line three, the word for wind is feng, which calls to mind Xifeng 熙鳳. (The characters are different, but a reader might well make the connection.) The line might thus be interpreted that it is Xifeng 熙鳳 who is the wind who blows on the fine flower, Patience 平儿. Later in the line (which is at this point still very clumsily translated), the word ping (simplified 凭 complex 憑) appears: it is a homophone for Ping’er 平儿. The line could be interpreted as “There is no reason to be jealous of Ping’er 平儿.”

In lines five and six, there is a parallelism which is only weakly represented in the English: yuan fei 原非 and que shi 确是. Both yuan and que are intensifiers; fei means “not” and shi means “is.”

The last lines speak to the poet’s admiration of Patience’s 平儿 stoic stance; she could have imitated her mistress Xifeng 熙鳳 (and lashed out) but instead she chose to repair her makeup. She then is able to return to the festivities. It is not as if nothing has changed, but the fundamental structure of her life goes on. Zhou Qi 周綺 articulates admiration for Patience’s forbearance.

Zhou Qi 周綺 is interested in female self-fashioning; see the colophon she wrote on the painting “Lady at her Dressing Table” by Wang Qiao 汪 乔, which concludes with the couplet addressed directly to the courtesan at the dressing table: “Choose your clothes carefully–they have to fit your person. Your morning toilette is no different from the evening one.”

Ann Waltner and her students discuss this poem in the video on the next page. Note that we have changed out mind about our translation of the poem since the video was shot.

Text from Chapter 44: Patience is Beaten (Hawkes Translation and Chinese text)

In chapter 44 of the novel, Wang Xifeng overhears her husband Jia Lian talking to Bao’er’s wife, with whom he is having an affair. The conversation runs as follows:

“The best thing that could happen to you” the voice was saying,”would be if that hell-cat wife of yours was to die.”

“Suppose she did,” Jia Lian’s voice said in answer, “and I married another one who turned out to be just as bad?”

“If she was to die,” said the first voice.” you ought to make Patience your Number One. I’m sure she’d be better than this one.”

“Patience won’t let me come near her nowadays,” said Jia Lian. “She has a lot to put up with, the same as me, that she doesn’t dare talk about. I don’t know, I reckon I must have been born under a hen-pecked husband’s star.”

Xifeng heard this shaking with fury. The couple’s praise of Patience made her at once suspect that Patience had been complaining about her behind her back. The fumes of wine mounted up inside her, clouding her judgment. Without pausing to reflect, she turned and struck Patience twice before kicking open the door and striding into the room. Then without more ado, she proceeded to sieze hold of Bao Er’s wife and belabour her, breaking off only to block the doorway with her body in case Jia Lian might think of escaping.

“Filthy whore!” she shouted. “Stealing a husband isn’t enough for you, it seems. You have to murder his wife as well!” She turned to Patience: “Go on Patience, your place is over there with them–with that whoremaster of yours and his other whore! You’re all three in this together. You hate me just as much as they do under that smarmy outside of yours!”

This was followed by several blows.

Poor Patience, overwhelmed by so much injustice, had only Bao Er’s wife on whom she could vent her feelings.

“If you have to do these shameful things,” Patience said to Bao Er’s wife, “at least you might leave me out of it.” And she began to pummel the woman in her turn.

Now Jia Lian had had a great deal to drink that day, and because of the euphoric state he was in, had taken insufficient precautions against surprise. Xifeng’s unexpected arrival had therefore left him completely at a loss. But Patience’s outburst was another matter. The wine he had drunk rekindled his forgotten valor; and whereas the anger and shame he felt at seeing Xifeng beat Bao Er’s wife had rendered him speechless, the sight of Patience doing the same thing so roused his valiancy that he shouted at her and gave her a kick.

“Little whore! You want to join in too, do you?”

Patience, whose gentle nature was easily overawed, at once left off, tearfully protesting that it was cruel of them to speak about her in such a way behind her back.

Xifeng, furious that Patience should be afraid of Jia Lian, rushed over and began striking her again, insisting that Patience should go on striking Bao Er’s wife and take no notice of him. Finding herself thus attacked on both sides simultaneously by the pair of them, Patience became so desperate that she dashed from the room, vowing that she would find a knife and kill herself and would undoubtedly have done herself an injury if the maids and nannies from outside had not seized her and gradually talked her out of it.

Selection from Chapter 44, where Patience is Beaten

鳳姐來至窗前,往裡聽時,只聽裡頭說笑道:「多早晚你那閻王老婆死了就好了!」賈璉道:「他死了,再娶一個,也這麼著,又怎麼樣呢?」那個又道:「他死了,你倒是把平兒扶了正,只怕還好些。」賈璉道:「如今連平兒他也不叫我沾一沾了,平兒也是一肚子委屈不敢說。我命裡怎麼就該犯了夜叉星!」

鳳姐聽了,氣的渾身亂戰。又聽他們都讚平兒,便疑平兒素日背地裡自然也有怨言了。那酒越發湧上來了,也並不忖度,回身把平兒先打了兩下子,一腳踢開了門進去,也不容分說,抓著鮑二家的就撕打。又怕賈璉走了,堵著門,站著罵道:「好娼婦!你偷主子漢子,還要治死主子老婆!--平兒,過來!你們娼婦們,一條藤兒,多嫌著我!外面兒你哄我!」說著,又把平兒打了幾下。打的平兒有冤無處訴,只氣得乾哭,罵道:「你們做這些沒臉的事,好好的又拉上我做什麼!」說著,也把鮑二家的撕打起來。

賈璉也因吃多了酒,進來高興,不曾做的機密。一見鳳姐來了,早沒了主意;又見平兒也鬧起來,把酒也氣上來了。鳳姐兒打鮑二家的,他已又氣又愧,只不好說的;今見平兒也打,便上來踢罵道:「好娼婦!你也動手打人!」平兒氣怯,忙住了手,哭道:「你們背地裡說話,為什麼拉我呢?」鳳姐見平兒怕賈璉,越發氣了,又趕上來打著平兒,偏叫打鮑二家的。平兒急了,便跑出來找刀子要尋死。外面眾婆子丫頭忙攔住解勸。

This text is taken from the Chinese Text Project. The website has the same text, with a built in dictionary, which will make it easier for language learners to read the text. Use the small blue arrows at the top of the page to navigate.

Text from Chapter 44: Patience at the Dressing Table (Hawkes Translation)

Later in chapter 44, after Patience has endured a humiliating beating at the hands of her mistress Wang Xifeng and Xifeng’s husband Jia Lian, she encounters Baoyu.

“Don’t be so upset, Patience,” said Baoyu consolingly.”I offer you an apology on their behalf.”

Patience laughed.

“It has nothing to do with you.”

“We’re all cousins,” said Baoyu. “What one of us does concerns all the others. If they have done you an injury, it’s up to me to apologize.”

He turned his attention to her appearance.

“What a pity! You’ve made your new dress all damp. Aroma’s dresses are in here. Why don’t you change into one of hers, then you can spray some samshoo on this one and iron it. You’ll need to do your hair again as well.”

He called for the junior maids to fetch water for washing and heat a flat-iron.

Up to that moment Patience had known only by hearsay of the remarkable understanding shown by Baoyu in his dealings with girls. He had deliberately kept away from her in the past, knowing her to be Xifeng’s confidante and (he supposed) Jia Lian’s cherished concubine. It had indeed been a source of frequent regret to him that he had been unable to show her how much he admired her. Seeing him like this for the first time, Patience reflected on the truth of what she had heard.

“He really has thought of everything,” she told herself, as she watched Aroma open up a large chest–specially for her–and select two scarcely worn garments from it for her to change into. Then, since the water had already arrived, she took off her own dress and skirt and quickly washed her face. Baoyu, who stood by smiling while she washed, now urged her to put on some makeup.

“If you don’t, it will look as if you are sulking,” he said. After all, it is Feng’s birthday, and Grandma did specially send someone to cheer you up.”

Inwardly acknowledging the reasonableness of this advice, Patience looked around her for some powder, but could not see any, whereupon Baoyu darted over to the dressing-table and removed the lid from a box of early Ming blue-and-white porcelain in which reposed the head of a white day-lily with five compact, stick-like buds on either side of the stem. Pinching off one of these novel powder-containers, he handed it to Patience.

“There you are. This isn’t ceruse, it’s a powder made by crushing the seeds of garden-jalop and mixing them with perfume.”

Patience emptied the contents of the tiny phial onto her palm. All the qualities required by the most expert perfumers were there: lightness, whiteness with just the faintest tinge of rosiness, and fragrance. It spread smoothly and cleanly on the skin, imparting to it a soft bloom that was quite unlike the harsh and somewhat livid whiteness associated with lead-based powders.

Then the rouge too, was different–not in the usual sheets or tissues, but a tiny white-jade box filled with a crimson substance.

Text from chapter 44: Patience at the Dressing Table (Chinese text)

寶玉忙勸道:「好姐姐,別傷心,我替他兩個賠個不是罷。」平兒笑道:「與你什麼相干?」寶玉笑道:「我們弟兄姐妹都一樣。他們得罪了人,我替他賠個不是,也是應該的。」又道:「可惜這新衣裳也沾了!這裡有你花妹妹的衣裳,何不換下來,拿些燒酒噴了,熨一熨,把頭也另梳一梳?」一面說,一面吩咐了小丫頭子們舀洗臉水,燒熨斗來。

平兒素昔只聞人說寶玉專能和女孩們接交。寶玉素日因平兒是賈璉的愛妾,又是鳳姐兒的心腹,故不肯和他廝近,因不能盡心,也常認為恨事。平兒如今見他這般,心中暗暗的敁敪,果然話不虛傳,色色想的周到。又見襲人特特的開了箱子,拿出兩件不大穿的衣裳,忙來洗了臉。寶玉一旁笑勸道:「姐姐還該擦上些脂粉,不然,倒像是和鳳姐姐賭氣的似的。況且又是他的好日子,而且老太太又打發了人來安慰你。」

平兒聽了有理,便去找粉,只不見粉。寶玉忙走至粧台前將一個宣窯磁盒揭開,裡面盛著一排十根玉簪花棒兒,拈了一根,遞與平兒,又笑說道:「這不是鉛粉,這是紫茉莉花種,研碎了,對上料製的。」

平兒倒在掌上看時,果見輕白紅香,四樣俱美。撲在面上,也容易勻淨,且能潤澤,不像別的粉澀滯。然後看見胭脂也不是一張,卻是一個小小的白玉盒子,裡面盛著一盒,如玫瑰膏子一樣。

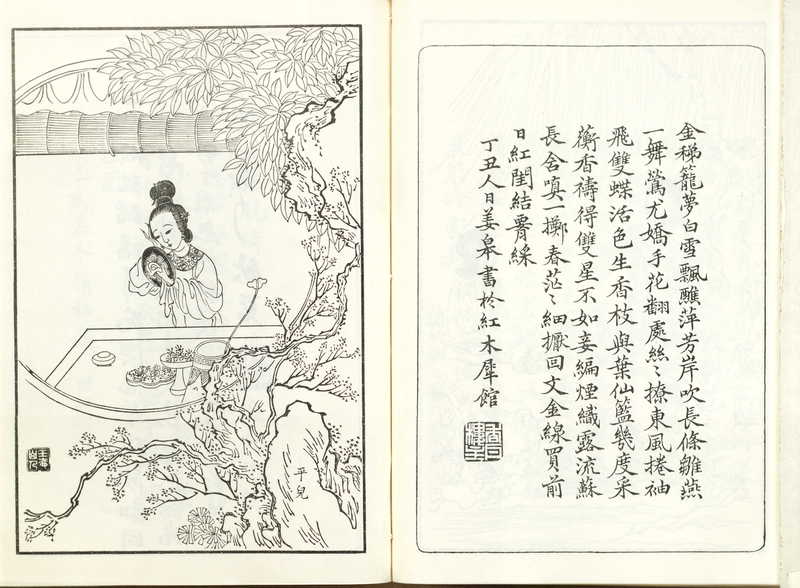

Another lady at her dressing table

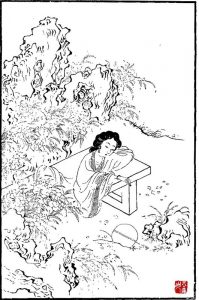

The theme of a woman at her dressing table is quite common in the art of the Qing dynasty. This woodblock print, which appeared in a late sixteenth or early seventeenth-century edition of the play Pipa ji 琵琶記 (The Lute) shows a woman dressing her hair. Note the fancy mirror.

The theme of a woman at her dressing table is quite common in the art of the Qing dynasty. This woodblock print, which appeared in a late sixteenth or early seventeenth-century edition of the play Pipa ji 琵琶記 (The Lute) shows a woman dressing her hair. Note the fancy mirror.

The caption reads “Facing the mirror, she does her hair and makeup.”

Zhou Qi 周綺: “Caltrop Studies Poetry” 香菱學詠

Zhou Qi “Caltrop [Xianglian 香菱] Studies Poetry” (a paraphrase)

In front of the flowers, under the moon, she concentrates her gaze.

With every bit of her tender being, she seeks inspiration.

Her focus on poetry earns her admiration;

Even given the situation she is in, she is not anxious.

She eats and sleeps only after she’s finished her poems;

Tears and laughter come only in her dreams.

Who knows if heaven will recompense you for your suffering?

But your fame does not rest on your resemblance to Keqing.

Translated by Ann Waltner’s reading group: Li Kan, Zhu Tianxiao, Jiang Yuanxin, Eric Becklin and Lars Christensen.

香菱學詠

花前月下自凝眸,寸寸柔腸寸寸搜。

著意個中誠足惜,處身如此不關愁。

眠餐好在吟成後,啼笑都從夢裡頭。

知否苦辛天報汝,芳名非仗可兒留。

The very first episode in the novel (in the narrative of mundane events) is the kidnapping of Caltrop. She reappears as Xue Pan’s chamber wife. It takes the residents of the Jia compound some time to figure out who she is. When Xue Pan leaves on a business trip, Caltrop moves into the garden with his sister Baochai, and begins to learn poetry.

The very first episode in the novel (in the narrative of mundane events) is the kidnapping of Caltrop. She reappears as Xue Pan’s chamber wife. It takes the residents of the Jia compound some time to figure out who she is. When Xue Pan leaves on a business trip, Caltrop moves into the garden with his sister Baochai, and begins to learn poetry.

Notes on the poem

The first four characters 花前月下 (translated as “In front of the flowers and under the moon”) are quite conventional and may suggest to the reader that Caltrop is still beginning as a student of poetry. The second line repeats a reduplicative: the word 寸 is repeated four times, which this translation more or less obscures. Reduplicatives are much commoner in classical Chinese than they are in modern English.

The last line refers to Qin Keqing 秦可卿, a daughter-in-law in the Jia 賈 household who died tragically. There are some indications that she may have been involved in an incestuous relationship with her father-in-law. The clearest evidence of this in the present version of the novel is the extreme grief with which he responded to her death and her extravagant funeral, which far exceeded what was ritually appropriate. Yu Pingbo 俞平伯 was one of the earliest scholars to assert unequivocally that the affair had taken place and that Keqing 可卿 did not die from illness but rather that she committed suicide. It is now clear that the commentator Zhiyan zhai 脂砚齋 (whose precise identity remains unknown, but who was a close associate of Cao Xueqin 曹雪芹, the author of the novel) asked that the incest be removed from the novel.

Commentators often paired characters in the novel with one another. It might be an exaggeration to say that the characters were doubles, but they were seen as pairs–for example, Aroma (Xiren 袭人) was paired with Baochai 寶釵; Nightingale (Zijuan紫鵑) was paired with Daiyu, and so on. Zhou Qi invokes the pairing of Caltrop (Xianglian 香菱) and Qin Keqing 秦可卿, but asserts that Caltrop’s (Xianglian 香菱) fate will not be like that of Keqing 可卿. (In chapter 7 two servants–Zhou Rui’s wife and Golden–agree that Caltrop resembles Qin Keqing.) Her talent will assure Caltrop (Xianglian 香菱) that she is remembered. Her talent found her a place among the cousins in the garden, and offered her a kind of redemption for her past.

Text from chapter 7: Caltrop

Only gradually do the residents of the Jia household become aware of Caltrop’s past. In chapter 7, a servant known to us only as Zhou Rui’s wife asks a servant named Golden about Caltrop, and then attempts to find out Caltrop’s story from the girl herself.

“Tell me,” Zhou Rui’s wife asked Golden, “is that little Caltrop the one they are always talking about who was bought just before they came to the capital? The one they had the murder trial about?”

“That’s her,” said Golden.

At that moment Caltrop herself came skipping up with a sunny smile on her face, and Zhou Rui’s wife took her by the hand and studied her curiously. Then she turned to Golden again.

“You know there’s something about this face that reminds me of Master Rong’s wife over at the Ning mansion.”

“That’s just what I’ve said.” Golden agreed.

Zhou Rui’s wife asked Caltrop how old she was and when she became a slave. Then she asked her where her parents were, what her age was, and what part of the country she came from. But to all of these questions Caltrop only shook her head and said that she didn’t remember.

Zhou Rui’s wife and Golden exchanged glances and sighed sympathetically.

Text from chapter 7: Caltrop (Chinese text)

周瑞家的問道:「那香菱小丫頭子,可就是時常說的,臨上京時買的,為他打人命官司的那個小丫頭嗎?」金釧兒道:「可不就是他。」正說著,只見香菱笑嘻嘻的走來。周瑞家的便拉了他的手細細的看了一回,因向金釧兒笑道:「這個模樣兒竟有些像偺們東府裡的小蓉奶奶的品格兒。」金釧兒道:「我也這麼說呢。」周瑞家的又問香菱:「你幾歲投身到這裡?」又問:「你父母在那裡呢?今年十幾了?本處是那裡的人?」香菱聽問,搖頭說:「不記得了。」周瑞家的和金釧兒聽了,倒反為歎息了一回。

Text from chapter 48: Caltrop moves into the Garden

Caltrop is a chamber-wife to Xue Pan, and when he leaves to go on a trade expedition, she moves into the garden and lives with Baochai. The garden delights her for many reasons, not the least of which is that it offers her the opportunity to learn poetry. In chapter 48, she addresses Baochai with great enthusiasm.

“Dear Miss,” said Caltrop. “Now that there is the time and the opportunity, will you teach me how to write poetry, please?”

Later in the chapter, she goes to visit Daiyu and makes the same request:

“Now that I’m here and have got more time to spare, do you think you could teach me how to write poetry? It would be such a piece of luck for me if you would.”

“You can make your kowtow and become my pupil if you like,” said Daiyu goodnaturedly. “I’m no expert myself, but I dare say I could teach you the rudiments.”

“Would you really?” said Caltrop. “Then I’ll be your disciple. But you must promise not to get impatient with me.”

“There’s nothing in it really,” said Daiyu. “There’s really hardly anything to learn. In Regulated Verse there are always four couplets: the “opening couplet,” the “developing couplet,” the “turning couplet,” and the “concluding couplet.” In the two middlle couplets, the “developing” and “turning” ones, you have to have tone-contrast and parallelism. That’s to say in each of these couplets the even tones of one line have to contrast with the oblique tones in the other and vice versa. and the substantives and non-substantives have to balance each other, though if you’ve got a really good, original line it doesen’t matter all that much even if the tone-contrast and parallelism are all wrong.”

“Ah, that explains it!” said Caltrop, pleased. “I’ve goit an old poetry book that I look at once and a while when I can find the time and I long ago noticed that in some of the poems the tone-contrast is very strict, while in others it’s not. Someone told me the rhyme:

For one, three, and five

You need not strive,

But two, four, and six

You must firmly fix.and at first that seemed to explain the exceptions. But then I found that in some old poems even the second, fourth, and sixth lines seeemd to have the wrong tones and I’ve been puzzling about it ever since. Now, from what you’ve just said, it sounds like these rules really aren’t important after all–that the most important thing is that the language should be original.”

“You’ve hit it exactly,” said Daiyu. “As a matter of fact, even the language is not of primary importance. The really important things are the ideas that lie behind it. If the ideas that lie behind it are genuine, there’s no need to embellish the language for the poem to be a good one. That’s what they mean when they say “not letting the words harm the meaning.”

So Daiyu gives her a book of one hundred poems by the poet Wang Wei.

Next morning, just as Daiyu had completed her toilet, a smiling Caltrop walked in, holding out the volume of Wang Wei and asking to exchange it for a volume of Du Fu’s heptasyllabic poems.

“How many of them do you think you can remember?” Daiyu asked her.

“I’ve been through all the ones marked with red circiles.” said Caltrop.

“And do you thonk you have learnt anything from them?”

“I think so,” said Caltrop. “Though I cannt be sure. Perhaps you can tell me.”

“Certainly,” said Daiyu. “Discussion is what I was hoping for. It is the only way of making progress.”

And the two young women then engage in an extended discussion of poetry.

Text from chapter 48: Caltrop moves into the Garden (Chinese text)

香菱笑道:「好姑娘!趁著這個工夫,你教給我做詩罷!」

香菱因笑道:「我這一進來了,也得空兒,好歹教給我做詩,就是我的造化了!」黛玉笑道:「既要學做詩,你就拜我為師。我雖不通,大略也還教的起你。」香菱笑道:「果然這樣,我就拜你為師,你可不許膩煩的。」黛玉道:「什麼難事,也值得去學?不過是起承轉合。當中承轉,是兩副對子:平聲的對仄聲;虛的對實的,實的對虛的。若是果有了奇句,連平仄虛實不對都使得的。」

香菱笑道:「怪道我常弄本舊詩偷空兒看一兩首,又有對的極工的,又有不對的;又聽見說,『一三五不論,二四六分明,』看古人的詩上,亦有順的,亦有二四六上錯了的:所以天天疑惑。如今聽你一說,原來這些規矩竟是沒事的,只要詞句新奇為上。」黛玉道:「正是這個道理。詞句究竟還是末事,第一是立意要緊。若意趣真了,連詞句不用修飾,自是好的:這叫做『不為辭害意』。」

一日,黛玉方梳洗完了,只見香菱笑吟吟的送了書來,又要換杜律。黛玉笑道:「共記得多少首?」香菱笑道:「凡紅圈選的,我盡讀了。」黛玉道:「可領略了些沒有?」香菱笑道:「我倒領略了些,只不知是不是,說給你聽聽。」黛玉笑道:「正要講究討論,方能長進。你且說來我聽聽。」

Zhou Qi 周綺 : “Xiangyun, Drunk, Sleeps among the Peonies” 湘雲醉眠芍藥

Shi Xangyun 史湘雲 is one of the cousins in the novel; she is not a character in the opera. This poem and these illustrations show one of the iconic scenes in the novel involving Xiangyun.

Zhou Qi: “Xiangyun, Drunk, Sleeps among Peonies”

Fair one in disarray, the lady is overcome by drunkenness,

The power of wine is hard to overcome as evening approaches.

In the endless spring breeze she is bound in spring sleep.

Almost unbearable, the rain of red blossoms covers her rouge face.

If she did not have “bones of jade,” she should be warm.

Fortunately, with her “flesh of ice,” she is not bothered by the chill.

In her reckless naïveté there is also delicate restraint.

It takes great effort for a poet to capture this scene.

Translation by Ellen Widmer, Beauty and the Book, 148-49.

Li Kan reads poem 湘云醉眠芍药

Chinese text of the poem in simplified characters:

Chinese text of the poem in simplified characters:

湘云醉眠芍药

席翻脂粉醉飞觞,酒力难支近夕阳。

无限春风困春睡,不胜红雨覆红妆。

倘非玉骨还宜暖,幸是冰肌未得凉。

一种娇憨又娇怯,画工要画费平章。

Chinese text of the poem in traditional characters:

湘雲醉眠芍藥

席翻脂粉醉飛觴,酒力難支近夕陽。

無限春風困春睡,不胜紅雨覆紅妝。

倘非玉骨還宜暖,幸是冰肌未得涼。

一種嬌憨又嬌怯,畫工要畫費平章。

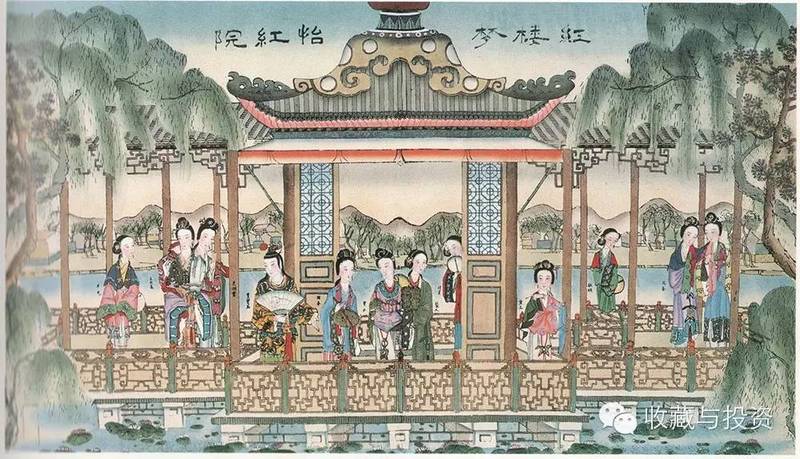

In the painting below, by Sun Wen 孙温, we see the full scene–we see both the party at which Shi Xiangyun 史湘雲 became inebriated and her nap outside. The painting uses a technique of continuous narration–we see the same figures both at the party and outside checking on Xiangyun 湘雲. Baoyu 寶玉, with his prominent red hair ornament, is the most identifiable of the figures. He can be clearly seen both at the party indoors and hovering over Xiangyun 湘雲.

Text from Chapter 62: Shi Xiangyun’s Inebriation

The scene of the novel in which describes Shi Xiangyun’s inebriation occurs in chapter 62. Here is the translation by David Hawkes:

They found Xiangyun where the maid had said, on a large stone bench in a hidden corner of the rookery, dead to the world. She was covered all over from head to foot with crimson petals from the peony bushes which grew about; the fan which had slipped from her hand and lay on the ground beside her was half covered in petals; and heaped-up peony petals wrapped up in a white silk handkerchief made an improvised pillow for her head. Over and around this petalled monstrosity a convocation of bees and butterflies was hovering distractedly. It was a sight the cousins found both touching and comical. They made haste to rouse her and lifted her up to a half-sitting position on the bench. But Xiangyun was still playing drinking games in her sleep…

And here is the original text:

都走来看时,果见湘云卧于山石僻处一个石凳子上,业经香梦沉酣,四面芍药花飞了一身,满头脸衣襟上皆是红香散乱,手中的扇子在地下,也半被落花埋了,一群蜂蝶闹穰穰的围着他,又用鲛帕包了一包芍药花瓣枕着。众人看了,又是爱,又是笑,忙上来推唤挽扶。湘云口内犹作睡语说酒令……

Zhou Qi 周綺 : “Skybright Dies and Becomes a Hibiscus Spirit” 晴雯死领芙蓉神 “

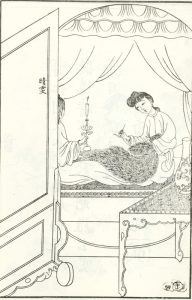

Skybright (Qingwen 晴雯) was a maid who was unusually skilled at needlework. When Baoyu 寶玉 damaged a Russian cloak that Grandmother Jia 賈母 had given him, Skybright 晴雯 was the only person who could mend it, despite the fact that she was, at the time very ill. She died shortly thereafter. In this illustration from the Honglou meng tuyong紅樓夢圖詠, she is shown sitting in bed, mending the cloak. We know it is dark because Baoyu, standing almost out of view to the left of the bed is holding up a candle so Skybright 晴雯 can see. (This episode is from chapter 52 of the novel.)

Skybright (Qingwen 晴雯) was a maid who was unusually skilled at needlework. When Baoyu 寶玉 damaged a Russian cloak that Grandmother Jia 賈母 had given him, Skybright 晴雯 was the only person who could mend it, despite the fact that she was, at the time very ill. She died shortly thereafter. In this illustration from the Honglou meng tuyong紅樓夢圖詠, she is shown sitting in bed, mending the cloak. We know it is dark because Baoyu, standing almost out of view to the left of the bed is holding up a candle so Skybright 晴雯 can see. (This episode is from chapter 52 of the novel.)

Zhou Qi “Skybright Dies and Becomes a Hibiscus Spirit” (a paraphrase)

One appearance of the tan-flower; your life was too short.

As I begin to write, how can I not have sympathy for you?

Even though he composed a foolish elegy, it doesn’t make up for all the wrongs.

If you really were a flower spirit, that would be the beginning of your fame.

You never used your beauty to achieve your wishes;

For your whole life, you were troubled by your cleverness.

This fact has always been the most heartbreaking.

You have severed ties with the mortal world, but not your ties with passion.

Translated by Ann Waltner’s reading group: Zhu Tianxiao, Li Kan, Eric Becklin, Jiang Yuanxin, Lars Christensen

晴雯死领芙蓉神

一现优昙命太轻,临题那得不怜卿。

便填痴诔难偿恨,真做花神始称名。

素愿何尝形色笑,平生转为误聪明。

从来此事销魂最,已断尘缘未断情。

Notes on the poem

First, some botanical notes. Furong (芙蓉) is often translated hibiscus, but can also be translated as lotus. David Hawkes has translated it as hibiscus; we follow that translation. The tan-flower (昙), sometimes translated as night blooming cereus, is a splendid flower that blooms rarely, briefly, and spectacularly.

First, some botanical notes. Furong (芙蓉) is often translated hibiscus, but can also be translated as lotus. David Hawkes has translated it as hibiscus; we follow that translation. The tan-flower (昙), sometimes translated as night blooming cereus, is a splendid flower that blooms rarely, briefly, and spectacularly.

Skybright’s death is described in chapter 78 of the novel. Baoyu is distraught at her death; to console him, a maid tells him that Skybright has become a hibiscus spirit. Baoyu composed a long elegy (lei 诔) to her. The elegy is foolish (chi 痴) for several reasons. First of all, Skybright had not become a spirit; Baoyu had been deluded by a spur-of-the moment story. But there is a second meaning: chi is also used to describe one who is foolish because he is deluded by passion; it is often used to describe Baoyu.

Skybright was very beautiful and was said to resemble Daiyu. She also had a sharp tongue, hence the reference to the cleverness which troubled her throughout her life. Some analyses of the novel suggest that maids in some ways serve as “doubles” to the main characters. In those analyses, Skybright is seen as a double to Daiyu, who is also beautiful and troubled by her quick wit.

In this painting by Sun Wen, Baoyu is making an offering to a hibiscus spirit, because he believes that upon her death, Skybright became a hibiscus spirit. He is holding the text of the elegy he has composed; he has set up a table in front of a hibiscus in order to make a proper offering to the spirit.

Zhou Qi 周綺: “Lamenting You Niang who Fell into a Trap” 苦尤娘遭賺墮計

Her grace was like flowers; her demeanor was like the radiance of the moon.

The Lord of the East should not have failed her.

Heartbroken, full of resentment for the quack medicine.

On the meandering river, it was hard to cross the “jealous wife ford.”She must have been drained of emotion when she returned to the Land of Illusion.

It is certain that she was full of hatred when she left the world of dust.

For beautiful women, it is almost always like this.

Heartbroken for a thousand autumns, a person with a bad fate.

translated by Ann Waltner’s reading group (Li Kan, Lars Christensen, Zhu Tianxiao, Jiang Yuanxin, Eric Becklin)

Text of poem in simplified characters:

苦尤娘遭赚堕计

花是丰姿月是神,东君应不负终身。

伤心漫怨庸医药,委曲难通妒妇津。

未必无情归幻境,定然有恨隔凡尘。

红颜大抵都如此,肠断千秋命薄人。

Text of poem in traditional characters:

苦尤娘遭賺墮計

花是豐姿月是神,東君應不負終身。

傷心漫怨庸醫藥,委曲難通妒婦津。

未必無情歸幻境,定然有恨隔凡塵。

紅顏大抵都如此,腸斷千秋命薄人.

Notes on poem

This poem is about You Erjie 尤二姐, whom Jia Lian 贾琏 married in secret. When Wang Xifeng 王熙風 (Jia Lian’s 贾琏 wife) found out, she brought You Erjie into the family compound and hounded her to death. The quack medicine probably refers to unsatisfactory medical treatment that You Erjie received while she was pregnant, which resulted in a miscarriage. We translated 委曲 as “meandering river”; it also means feeling resentful. Both meanings are carried in this line. We have translated two different phrases as heartbroken:傷心 and 腸斷. The first literally means “wounded heart/mind” and the second literally means “guts were broken.” In some contexts, gut-wrenching is a good translation for 腸斷, but it does not seem to work here.

Zhou Qi 周綺: “Daiyu Burns her Poems” 黛玉焚詩

Lin Daiyu Burns her Poems (a paraphrase)

不辩嗁痕舆墨痕 I cannot distinguish the traces of her tears from the traces of her ink.

無情火斷有情根 The unfeeling fire obliterates the root of her passion.

者宵果應燈花谶 This night, her destiny is marked by the candle patterns

往日空憐蜀鳥魂 In days past, in vain she sympathized with the spirit of the cuckoo

慧業已随人遯世 Once her works were gone, she left the mortal world.

癡鬟休為竹開門 Foolish maids, do not open the gates to the bamboo lodge.

鸭鑪獸炭寒如水 The charcoal in the duck-shaped censer is as cold as water.

剩的心頭一縷温 And all that remains in my heart is a wisp of warmth.

The episode that this poem invokes comes from chapter 97 of the novel, which is in the text box at the bottom of this page.

The motif of a woman burning her poetry is one we see elsewhere in Qing dynasty writings about women, real and fictional. One of the reasons a woman would destroy her literary works is the Confucian dictate that a woman should not speak or be talked about beyond the domestic realm. In Daiyu’s case, articulated in both the novel and this poem, we see a specific identity between her works (huiye 慧業) and her self (ren 人). She knows she will die, so she burns her works. Her life is over; her writings are gone.

Translation by Ann Waltner and the reading group (Li Kan, Zhu Tianxiao, Jiang Yuanxin, Eric Becklin, Lars Christensen, Jin Hui-han and Rachel Kronik.)

Text from Chapter 97: Daiyu Burns her Poems (Hawkes Translation)

Daiyu’s health was always fragile, but it takes a turn for the worse in chapter 97 after she learns that Baoyu is to marry Baochai. (The family had hoped to keep the news from her but she learns anyway.) The narrative unfolds as follows:

Previously, when she had been ill, Daiyu had always received frequent visits from everyone in the household, from Grandmother Jia down to the humblest maid-servant. But now not a single person came to see her. The only face she saw looking down at her was her maid Nightingale. She began to feel her end drawing near, and struggled to say a few words to her.

“Dear Nightingale! Dear sister! Closest friend! Though you were Grandmother’s maid before you came to serve me, over the years you have become as a sister to me…”

She had to stop for breath. Nightingale felt a pang of pity, was reduced to tears and could say nothing. After a long silence, Daiyu began to speak again, searching for breath between words.

“Dear sister! I am so uncomfortable lying down like this. Please help me up and sit next to me.”

“I don’t think you should sit up, Miss, in your condition. You might get cold in the draft.”

Daiyu closed her eyes in silence. A little later she asked to sit up again….

She told Snowgoose to come closer.

“My poems…”

Her voice failed, and she fought for breath again. Snowgoose guessed that she meant the manuscripts that she had been revising a few days previously, went to fetch them and laid them on Daiyu’s lap. Daiyu nodded, then raised her eyes and gazed in the direction of a chest that stood on a stand close by. Snowgoose did not know how to interpret this and stood there at a loss.

Snowgoose figures out that what Daiyu wants is handkerchiefs that Baoyu had sent on which she had inscribed poems. Daiyu speaks

“Light the lamp,” she ordered.

Snowgoose promptly obeyed. Daiyu looked into the lamp, then closed her eyes and sat in silence. Another fit of breathlessness. Then:

“Make up the fire in the brazier.”

Thinking she wanted it for the extra warmth, Nightingale protested.

“You should lie down, Miss, and have another cover on. And the fumes from the brazier might be bad for you.”

Daiyu shook her head, and Snowgoose reluctantly made up the brazier, placing it on its stand on the floor. Daiyu made a motion with her hand, indicating that she wanted it moved up onto the kang. Snowgoose lifted it and placed it there, temporarily using the floor-stand, while she went out to fetch the special stand they used on the kang. Daiyu, far from resting back in the warmth, now inclined her body slightly forward–Nightingale had to support her with both hands as she did so. Dayu took the handkerchiefs in one hand, Staring into the flames and nodding thoughtfully to herself, she dropped them into the brazier. Nightingale was horrified, but much as she would have liked to snatch them from the flames, she did not dare move her hands and leave Daiyu unsupported. Snowgoose was out of the room, fetching the brazier-stand, and by now the handkerchiefs were all ablaze.

“Miss!” cried Nightingale. “What are you doing?”

Daiyu then drops the manuscripts onto the fire. Snowgoose returns:

She saw Daiyu drop something into the fire, and without knowing what it was, rushed forward to try to save it The manuscripts had caught at once and were already ablaze. Heedless of the danger to her hands, Snowgoose reached into the flames and pulled out what she could, throwing the paper on the floor and stamped frantically on it. But the fire had done its work, and only a few charred fragments remained.

Zhou Qi 周綺: “Miaoyu, Hearing the Qin, Becomes Enlightened” 妙玉听琴警悟

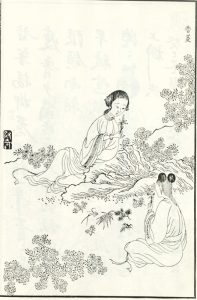

In these prints, Baoyu 寶玉 and Adamantina (Miaoyu 妙玉) are sitting outside the Bamboo Lodge (Daiyu’s residence) and are listening to her play the qin.

In these prints, Baoyu 寶玉 and Adamantina (Miaoyu 妙玉) are sitting outside the Bamboo Lodge (Daiyu’s residence) and are listening to her play the qin.

Miaoyu, on Hearing the Qin, is suddenly Enlightened (a paraphrase)

She understands the subtleties but does not speak of them.

A song, played on the qin ; she can bear to hear it to the end.

A good dream, from which she had not yet awakened, this guest with the everlasting sorrow.

The beauty has ended up with the pitiful wormIn the past she had suffered from the burden of obsession.

But from now on she takes refuge in the knowledge that appearance is empty.

Endless heartbreak becomes her only thought

Echoes attach themselves to the cloudy moonlight.

Text of poem in simplified Chinese characters:

妙玉听琴警悟

机微领略不言中,一曲丝桐忍听终。

好梦未醒长恨客,美人已定可怜虫。

从前枉受情痴累,此后都归色相空

无限伤心成独想,余音任付月溟朦。

Text of poem in complex Chinese characters:

妙玉聽琴警悟

機微領略不言中,一曲絲桐忍聽終。

好夢未醒長恨客,美人已定可憐蟲。

從前枉受情癡累,此後都歸色相空。

無限傷心成獨想,餘音任付月溟朦。

Translated by Ann Waltner’s reading group: Zhu Tianxiao, Li Kan, Eric Becklin, Lars Christensen, Jiang Yuanxin

The episode in which Miaoyu and Baoyu listen to Daiyu playing the qin 琴 is in chapter 87; the episode in which she is kidnapped is in chapter 112.

More on the qin, including demonstration of qin playing by Liu Li, is available here.

Text from chapter 87: Miaoyu Hears the Qin

In chapter 87, Baoyu is walking Adamantina (Miaoyu) home.

Their winding path led them near the Naiad’s House, and as they approached they heard strains of music in the air. “That’s a qin,” said Adamantina. “Where could it be coming from, I wonder?” “It must be cousin Lin playing in her room,” replied Baoyu. “Really? Is that another of her accomplishments? I’ve never heard her mention it.”

Baoyu repeated what Daiyu had told him.

“Shall we go and watch?” he suggested. “You mean listen, I suppose?” said Adamantina. “One listens to the qin. One never watches.” “There you are!” said Baoyu with a grin. “I said I was a common sort of mortal.” They had now reached a rockery close to the Naiad’s House. They sat down and listened in silence, touched by the poignancy of the melody. Then a murmuring voice began to chant:

Autumn deepens and with it

The wind’s bitter moan.

My love is far away;

I mourn alone.

Gazing in vain

For a glimpse of home,

I stand at my balcony

Tears bedew my gown.After a brief pause, the chant began again:

Hills and lakes melt into distant night.

Through my casement shines the clear light

Of the moon

And the sleepless Milky Way.

My thin robe trembles

As wind and dew alight.There was another brief pause. Adamantina said to Baoyu: “The first stanza rhymed on ‘moan,’ the second on ‘night.’ I wonder how the next will rhyme?”

The chant began again from within:

Fate denies you freedom, holds you bound;

Inflicting on me too a heavy wound.

In closest harmony our hearts resound

In contemplation of the Ancients

Is solace found.“That must be the end of the third stanza” said Adamantina. “How tragic it is!” “I don’t know anything about music,” said Baoyu. But just from the way she sang, I found it terribly sad.”

There was another pause and they heard Daiyu tuning her qin.

“That tonic B-flat of hers is too sharp for the scale,” commented Adamantina.

Then the chanting began again.

Alas this particle of dust, the human soul,

Is only playing out a predetermined role.

Why grieve to watch

The Wheel of Karma turn?

A moonlike purity remains

My constant goal.

As she listened, Adamantina turned pale with horror.“Just listen to the way she suddenly uses a sharpened fourth there! Her intonation is enough to shatter bronze and stone! It’s much too sharp!” “What do you mean, too sharp”” asked Baoyu. “It will never take the strain.” As they were talking, they heard a sudden twang and the tonic string snapped, Adamantina stood up at oce and began to walk away.

“What’s the matter?” asked Baoyu.

She walked off, leaving Baoyu in a state of great confusion. Eventually he too made his way dejectedly home. And there our narrative leaves him.

Text from chapter 87: Miaoyu Hears the Qin (in Chinese)

於是二人別了惜春,離了蓼風軒,彎彎曲曲,走近瀟湘館,忽聽得叮咚之聲。妙玉道:「那裡的琴聲?」寶玉道:「想必是林妹妹那裡撫琴呢。」妙玉道:「原來他也會這個嗎?怎麼素日不聽見提起?」寶玉悉把黛玉的事說了一遍,因說:「偺們去看他。」妙玉道:「從古只有聽琴,再沒有看琴的。」寶玉笑道:「我原說我是個俗人。」說著,二人走至瀟湘館外,在山子石上坐著靜聽,甚覺音調清切。只聽得低吟道:風蕭瀟兮秋氣深,美人千里兮獨沉吟。望故鄉兮何處?倚欄杆兮涕沾襟。歇了一回,聽得又吟道:山迢迢兮水長,照軒窗兮明月光。耿耿不寐兮銀河渺茫,羅衫怯怯兮風露涼。又歇了一歇,妙玉道:「剛纔『侵』字韻是第一疊,如今『陽』字韻是第二疊了。偺們再聽。」裡邊又吟道:子之遭兮不自由,予之遇兮多煩憂。之子與我兮心焉相投?思古人兮俾無尤。妙玉道:「這又是一拍。--何憂思之深也!」寶玉道:「我雖不懂得,但聽他聲音,也覺得過悲了。」裡頭又調了一回絃。妙玉道:「『君絃』太高了,與『無射律』只怕不配呢。」裡邊又吟道:人生斯世兮如輕塵,天上人間兮感夙因。感夙因兮不可惙,素心何如天上月?妙玉聽了,訝然失色道:「如何忽作變徵之聲!音韻可裂金石矣!只是太過。」寶玉道:「太過便怎麼?」妙玉道:「恐不能持久。」正議論時,聽得「君弦」蹦的一聲斷了。妙玉站起來,連忙就走。寶玉道:「怎麼樣?」妙玉道:「日後自知,你也不必多說。」竟自走了。弄得寶玉滿肚疑團,沒精打彩的,歸至怡紅院中。不表。

Zhou Qi:周綺 “Faithful Follows her Mistress in Death and Completes her Virtue” 鴛鴦殉主全貞

“Yuanyang xun zhu chuan zhen”

Faithful Follows her Mistress in Death and Completes her Virtue (a paraphrase)

Your heart was always difficult to win;

You served your mistress until her death, and then you met the silken cord.

You should have had many days remaining, but how could you be willing to remain alive?

Other than your own self, what did you have to rely on?

Do not pity this crushed jade; she extinguished all her sorrow,

But rather criticize those who use inappropriate behavior to gain reputation.

You were the first to awaken from the dream

Could any of the twelve beauties do this?

Translated by Ann Waltner’s reading group: Zhu Tianxiao, Li Kan, Eric Becklin, Lars Christensen and Jiang Yuanxin

The poem in simplified characters:

鸳鸯殉主全贞

芳心迟早固难胜,侍得人归付幅绫。

为日之多岂所愿?此身以外更何凭?

休怜碎玉销香恨,应愧沽名钓誉称。

竟可梦中先醒梦,金钗十二有谁能?

The poem in traditional characters:

鴛鴦殉主全貞

芳心遲早固難勝,侍得人歸付幅綾。

為日之多豈所願?此身以外更何憑?

休憐碎玉銷香恨,應愧沽名釣譽稱。

竟可夢中先醒夢,金釵十二有誰能?

Notes on Poem

Faithful (Yuanyang 鴛鴦) is the most important of Grandmother Jia’s maids. The first line probably refers to Faithful’s (Yuanyang 鴛鴦) adamant refusal to become the concubine of Jia She 賈赦. Grandmother Jia 賈母 supports her in this refusal; otherwise, it would have been difficult for Faithful (Yuanyang 鴛鴦) to refuse Jia She賈赦 . When Grandmother Jia 賈母 dies, Faithful( Yuanyang 鴛鴦) hangs herself; she meets the silken cord. Her suicide may have been motivated by grief and loyalty–the Chinese term is 殉主 which means “to follow a master/ruler in death.” But she may also have feared what her life would be like without her protector.

The Twelve Beauties refers to the Twelve Beauties of Jinling (金釵十二), whose fates Baoyu learns about (albeit through rather crytpic poems) in his dream in chapter five. Faithful’s (Yuanyang 鴛鴦) awakening from the dream costs her her life. Zhou Qi 周綺 asks whether any of the other major female characters in the novel would have been able to do that.

One could also translate the phrase 全貞 as “preserves her virginity.”

Zhou Qi 周綺:”The Goddess of Frost and the Lady of the Moon: Li Wan Mourns Daiyu”

The Goddess of Frost and the Lady of the Moon: Li Wan mourns Daiyu

In the moonlight, in the frost, she planned to take flight freely.

This outstanding sister took the lead in literary talents.

She must have invited jealousy because of her pure genius.

How is it right for a young girl’s life to end while she is young?If there is a purpose for passion, let it be profound.

When illness falls on the innocent, it is most pathetic.

Bamboo willfully welcomes people, yet no one comes [when Daiyu dies]

Alas, only I am filled with tears.

The English translation is from Widmer, Beauty and the Book, 149.

This is the text of the poem in traditional characters:

青女素娥李紈悲黛玉

月中霜裡擬翩翩,姊妹班頭掌翰仙。

定為清才遭白眼,豈宜紅粉逝青年.

情雖有為情應篤,病到無辜病最憐。

竹自迎人人寂寂,嘻籲我獨淚潸然

This is the text of the poem in simplified characters.

青女素娥李纨悲黛玉

月中霜里拟翩翩,姊妹班头掌翰仙。

定为清才遭白眼,岂宜红粉逝青年?

情虽有为情应笃,病到无辜病最怜。

竹自迎人人寂寂,嘻吁我独泪潸然。

Notes on the poem

The first line of the poem refers to Daiyu’s 黛玉 wanting to take flight freely, which might seem odd. But if we look closely at the poems Daiyu 黛玉 composes in chapter 27 as she is sweeping flowers, she talks about wanting to fly. The precise lines (in Paul Rouzer’s translation) are: “I wish that below my arms I could grow a pair of wings, And following flowers fly away to the very edge of the sky.” (願奴脅下生雙翼,隨花飛到天盡頭。) Paul Rouzer discusses the poems that Daiyu 黛玉 writes in chapter 27 here.

Daiyu’s residence was the Bamboo Lodge; the line “Bamboo willfully welcomes people” may refer to the normal sociability of her residence. But as Daiyu 黛玉 was dying, virtually all members of the family were attending the wedding of Baoyu 寶玉 and Baochai 寶釵. Even Daiyu’s maid Snowgoose (Xueyan 雪雁) was at the wedding. Li Wan 李紈 did not attend the wedding, because it was thought that as a widow, she might bring bad luck to the young couple.

Zhou Qi 周綺: “Lament at Yi hong Courtyard” 水寒雪冷慧婢恨怡红

Cold Water. Icy Snow; the Clever Maid hates Baoyu

The wind and rain are jealous of the flowers’ grace.

Righteous indignation is focused on the “little nurturer.”

Finally, at that moment, it became clear that it was only a dream.

Truly, it is hard to rely on this lovesickness.

How could the spirit of Baoyu not have regrets?

How did the passion of Daiyu become such an obsession?

Those heartbroken ones, where can they go to air their grievances?

She was ordered to stand, but she did not last long.

Or another try

The jealous flowers, wind and rain, exhaust the flowers grace

Translated by Ann Waltner’s reading group: Zhu Tianxiao, Eric Becklin, Jiang Yuanxin, Lars Christensen

水寒雪冷慧婢恨怡红

妒花风雨瘁花姿,义愤偏重小侍儿。

果易分明仍一梦,信难凭准是相思。

怡红意气能无恨,湘馆情怀为甚痴?

几许伤心何处诉?顿教重立不多时。

Notes on the Poem: We have translated yihong 怡红 as Baoyu because it is the name of his residence. David Hawkes translates it as “Green Delights.” (Yi hong would be more literally translated as “Red Delights” but Hawkes thinks that red does not have the same connotations in English as it does in Chinese, of youth and gaiety. Thus he translates the residence name as “Green Delights.”)

The clever maid may be Snowgoose (Xueyan 雪雁), Daiyu’s maid. Xiao shier 小侍儿 also refers to Baoyu: as the stone in a previous life he nurtured the Crimson Pearl Flower, who was reborn as Daiyu. In the novel the stone is referred to as shenjing shizhe. We have translated xiangguan 湘馆 as Daiyu 黛玉 because it is the name of her residence. David Hawkes translates it as Naiad’s House.

In our interpretation of the poem, we imagine the clever maid to be Snowgoose (Xueyan 雪雁). She is required to be an attendant of Baochai at the wedding, so as to persuade him that he is in fact marrying Daiyu 黛玉. She is thus complicit in his deception. (Daiyu’s 黛玉 other maid, Nightingale (Zijuan 紫鹃, manages to stay with Daiyu 黛玉.) At the moment that the marriage takes place, Snowgoose (Xueyan 雪雁) realizes that the union of Baoyu 寶玉 and Daiyu 黛玉 had been but a dream. The very last line could refer to Snowgoose–who did not stay at the wedding for long. Or it could refer to Daiyu 黛玉, who did not live long. We like the idea of reading it as meaning both.

Zhou Qi 周綺 Poem about Yuanchun

In a cage even more remote than the blue of the sky,

Your youth will not last long, you cannot help regretting this.

You have learned that a beauty does not have a bad fate,

But in this life you have missed out on girlish innocence.

Translation by Widmer, Beauty and the Book, 300.

樊房更比碧天沈,春不常留恨不禁。修到紅顏非薄命,此生又缺女兒心。

Notes on poem

Yuanchun 元春 (who is referred to as Princess Jia in the Sheng/Hwang opera) is Baoyu’s 寶玉 elder sister. She is an imperial consort, a concubine of the emperor, a position which brings the family honor, but which means that they rarely see her.

The word translated as cage (fan 樊) is part of a compound (fanlong 樊籠) which means birdcage. The metaphor of the caged bird recurs throughout the novel.

The word translated as youth (chun 春) literally means spring, and is the second syllable of Yuanchun’s 元春 name. Thus, the second line of the poem could also be read “You, Yuanchun, will not/did not live long,” and in fact Yuanchun does die prematurely.

The phrase in the third line “a beauty does not have a bad fate” turns the common phrase “a beauty has a bad fate” on its head. But the poem ends with a regretful tone: the price Yuanchun has paid for avoiding a bad fate is high: it is nothing less than the loss of her youth.

This poem is not included among the ten published in Zhou Qi’s husband’s Wang Xilian ping Honglou meng.

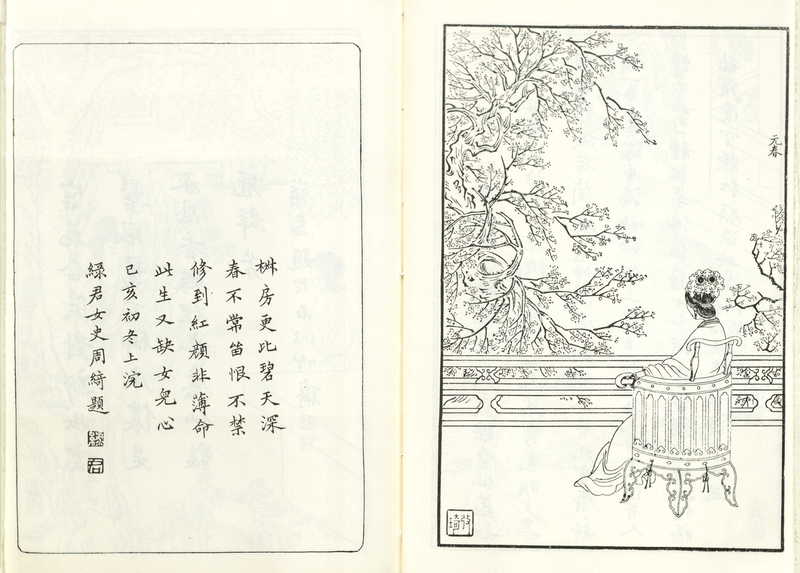

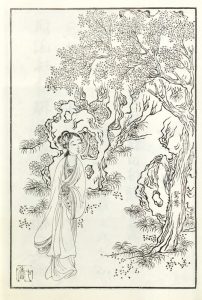

Notes on illustration

In the illustration above from the Honglou meng tu yong 紅樓夢圖詠, Yuanchun is sitting quietly, alone. We do not see her face, which may suggest that her role as imperial consort has deprived her of her identity (her face) as well as her girlish innocence. That image is in clear contrast with the pomp of her official position, clealy represented in the painting below by Sun Wen, which shows her return home for a rare visit. The Grandview Garden (Daguanyuan 大觀園) was constructed for the purpose of that visit. More details of Yuanchun’s 元春 visit home are in the discussion of Qing politics here.

This poem is included in the Honglou meng tuyong, a collection of illustrations of characters in the novel with accompanying poems. The calligraphy is meant to reproduce Zhou Qi’s 周綺 own hand. Of course a woodblock copy is only an approximation, but nonetheless it provides a sense of Zhou’s calligraphy. Compare this with her colophon on a painting by Wang Qiao 汪喬 , on the next page.

Zhou Qi 周綺 Colophon on Wang Qiao 汪喬 Painting

Zhou Qi 周綺 composed a colophon on a 1654 painting by Wang Qiao 汪喬, “A Woman at her Dressing Table,” which is held by the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. If you follow this link, you will be led to a zoomable photograph of the image on the website of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. If you read Chinese, look carefully at the bottom of the colophon. You will find the words 初稿 chu gao, which literally mean “first draft.” The painting was about 150 years old when she inscribed the colophon on it; Zhou Qi 周綺 was clearly not using it for calligraphy practice. It is likely that the phrase is a polite deprecatory phrase, to discount the labor and the skill that went into the making of the colophon. We should not over-read this; deprecatories were commonly used by both men and women in Qing China. Nonetheless, it is unusual to see the phrase “first draft” attached to a colophon. We should remember the way Zhou Qi 周綺 talks about how she first encountered the novel–it was lying on her husband’s desk and she casually picked it up.

Here is a transcription of the colophon:

幾生修到畫中人 柳暗花明絕俗塵

廿四番風吹不著 一編黃卷度三春紅桃碧柳傍湖山 一抹闌干六曲灣

應為惜花春起早 滿身風露理雲鬟春風柔較柳絲柔 鶯燕無聲小院幽

莫訝綠鬢來悄悄 粉奩香盒未曾收今春天氣總晴陰 生怕風吹愛月臨

為一瓶花簾半捲 乍寒乍暖替當心自然雲影襯朝霞 人面休疑陌上花

秋水一汪書一卷 管他春色編天涯紗窗日影上遲遲 今早春寒昨夜知

斟酌衣衫須稱體 曉妝無異晚妝時

And here is a translation:

How many lives did it take you to become a person in this picture?

Willows are dark, flowers are bright; they stand out from the dusty world.

The fragrant wind from the twenty-four bridges cannot reach her.

With one scroll of Daoist text she passes her youthful years.Red peaches and green willows by the lakes and mountains.

One stretch of balustrade with six bends.

It must be for the love of flowers that she rises early,

Enshrouded in wind and dew, she arranges her cloud-like hair.The spring wind is gentler than silken willow branches,

The orioles and swallows are silent and the small courtyard is quiet.

Do not be surprised that the servant arrives noiselessly.

The cosmetics case and the incense box have not yet been packed away.This spring the weather is unpredictably cloudy.

She fears the wind blowing but loves the coming of the moon,

For one vase of flowers, the curtain is half rolled up.

[The weather] being by turns cold and hot, I worry about her.In all naturalness, the shadows of clouds frame the morning glow.

Do not mistake her face for the flower by the wayside.

One deep gaze from her eye, one scroll of books.

Why care about spring spreading to the ends of the earth.On the gauze windows, the sun’s shadows rise slowly.

This morning’s spring chill–you knew about it last night.

Choose your clothes carefully–they have to fit your person.

Your morning toilette is no different from the evening one.

Translation modified slightly from Widmer, Beauty and the Book, 198-99.

Notes on poem

In line 2, the phrase translated “the dusty world” is su chen 俗塵. Su 俗 means secular, as opposed to sacred, and chen is often used in Buddhist texts to mean the mundane world. Thus the willows and flowers the poet is talking about do not seem to be a part of the mundane world. Widmer glosses the phrase “The fragrant wind from the twenty-four bridges cannot reach her” as suggesting that the woman in the painting is untainted by the sensual associations of the courtesan quarters. Widmer also glosses “enshrouded in wind and dew” as suggesting difficult circumstances.

In the fifth stanza, the phrase “flower by the wayside” suggests a beautiful woman, perhaps a courtesan, who has been discarded by a lover.

The phrase translated “Daoist Scrolls” is 黃卷 huang juan, whose literal meaning is yellow scrolls. The phrase does in fact mean Daoist scrolls; but the translation necessarily obscures the color. The poem is vivid with color–the red of the flowers, the green of the willows. The yellow of the text adds to the vividness of the color, and perhaps suggests a connection between text and nature–they are both a part of a world of color.

The scene being described–the peaches, the willows, the balustrade—is not the scene in the painting, but rather a scene in the poet’s imagination. Or, to be more precise, it is scene which the poet is inserting in the courtesan’s imagination.

Notes on painting

This painting is sometimes called “Lady at her Dressing Table.” If you look closely at the painting (and to see this you may need to go to website of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and zoom in on the painting), you will see that shoes are peeking out from under the gowns of both the woman at the dressing table and the woman making the bed. This clearly indicates that the women are courtesans–no Qing dynasty painter would have portrayed a lady’s bound feet. The rumpled bedclothes are clearly an indication that sexual activity has recently taken place.

Suggestions for further reading: Ellen Widmer, Beauty and the Book.

Colophon

|

|

Colophon is the term used to describe a text, often but not always a poem, written on a painting. Sometimes a colophon is written by the painter, but more often it is written by someone else–sometimes a friend or a patron, but also often by a later collector.

The writing of colophons on paintings suggests that the painting and the viewer exist in a dynamic relationship. A colophon permanently alters the painting and changes the spatial relationships in the painting. The painter thus does not have the last word on the construction of the painting.

The two images above are of Wang Qiao’s 王喬 painting which is normally entitled “A Lady at her Dressing Table,” held at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. The image at the top left is a photograph of the museum as it looks today, with a colophon by the poet and painter Zhou Qi 周綺(1814-1864) in the upper lefthand corner. The colophon in the painting is a square block, which balances both the block of the bed and the block of the dressing table. It seems like it is an integral part of the composition of the painting.

The second image was digitally reconstructed by Jay Kim using the Erase function in Photoshop so that we may see what it looked like before Zhou Qi 周綺 set her brush to write the colophon. Especially after our eyes have become accustomed to seeing the painting with the colophon, the painting without the colophon looks almost bare. Is it our imagination, or does the blank space in the right of the painting seem as if it is inviting someone to write a colophon?

The last two characters in the colophon are chu gao (初稿) which literally means rough draft. The words cannot have that meaning here–one does not use an old painting to practice calligraphy. Rather, the phrase is probably a self-deprecatory phrase, suggesting Zhou Qi’s 周綺modesty to the viewer of the painting and the reader of the colophon.

Questions

What are some of the ways in which knowing about colophons might change the way you look at Chinese paintings?

Discussion at MIA of Wang Qiao painting

Ann Waltner, Karil Kucera, and Kathleen Ryor discuss the Wang Qiao painting and Zhou Qi’s colophon in this video. They begin by talking about a narrative embroidery with scenes from the novel. For more about the embroidery, see this link.

Mia video on Wang Qiao painting

And Mia’s celebration of 100 years with 100 videos also features the painting by Wang Qiao.