Lin Daiyu 林黛玉

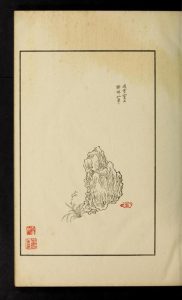

Lin Daiyu 林黛玉 is the earthly incarnation of the Crimson Pearl Flower. In a previous life, Baoyu 寶玉 had been a stone, and, as a stone, had captured water with which he nourished the flower. As a result, Daiyu 黛玉 owes Baoyu寶玉 a debt of tears, to repay the water which had sustained her life. The attentive reader will realize that the debt of tears means that there is no happy ending for Daiyu 黛玉. The illustration to the left, of a stone and a crimson pearl flower, opens the Honglou meng tuyong 紅樓夢圖詠, a collection of illustrations of characters from the novel and poems about those characters published in 1879. As in the illustration that opens the first published version of the novel which we saw on the page about Baoyu 寶玉, this illustration underscores the cosmological implications of the plot: Baoyu 寶玉 is the stone and Daiyu 黛玉 is the flower.

Lin Daiyu 林黛玉 is the earthly incarnation of the Crimson Pearl Flower. In a previous life, Baoyu 寶玉 had been a stone, and, as a stone, had captured water with which he nourished the flower. As a result, Daiyu 黛玉 owes Baoyu寶玉 a debt of tears, to repay the water which had sustained her life. The attentive reader will realize that the debt of tears means that there is no happy ending for Daiyu 黛玉. The illustration to the left, of a stone and a crimson pearl flower, opens the Honglou meng tuyong 紅樓夢圖詠, a collection of illustrations of characters from the novel and poems about those characters published in 1879. As in the illustration that opens the first published version of the novel which we saw on the page about Baoyu 寶玉, this illustration underscores the cosmological implications of the plot: Baoyu 寶玉 is the stone and Daiyu 黛玉 is the flower.

In her life on earth, Daiyu 黛玉 is the daughter of Jia Min 賈敏, the beloved daughter of Grandmother Jia 賈母. When Jia Min 賈敏 married Lin Ruhai 林如海, she moved south to Suzhou 蘇州 with him. Her daughter Daiyu 黛玉 was thus born and raised in the south, and her return to the Jia 賈 mansion upon the death of her mother early begins the story of the love triangle among the cousins Daiyu 黛玉, Baoyu 寶玉, and Baochai 寶釵.

She is talented and witty and lovely, and soon wins the admiration of most members of the Jia family. But her health is fragile, and she is constantly aware that she is an “outsider” in what seems at the beginning to be a gentle and luxurious life in the Jia 賈 mansion. (The Chinese term for relatives through a female line is wai 外, which literally means “outsider.”) Her frailty, her insecurities, and her somewhat difficult disposition also make her a less than ideal life partner for Baoyu 寶玉.

She is talented and witty and lovely, and soon wins the admiration of most members of the Jia family. But her health is fragile, and she is constantly aware that she is an “outsider” in what seems at the beginning to be a gentle and luxurious life in the Jia 賈 mansion. (The Chinese term for relatives through a female line is wai 外, which literally means “outsider.”) Her frailty, her insecurities, and her somewhat difficult disposition also make her a less than ideal life partner for Baoyu 寶玉.

In spite of this, she is an enormously sympathetic character, and readers and viewers for more than two centuries have regretted the impossibility of her union with Baoyu.

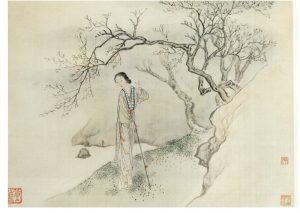

In the image above, painted by Fei Danxu (費丹旭 1801-1850), we see Daiyu burying flowers. She fears that the flowers will become spoiled, and so she collects them and places them in a silk bag to bury. The text which describes her burying the flowers is in chapter 23 in the novel; in chapter 27 she composes a sequence of poems on burying the flowers. Paul Rouzer translates and discusses the poems.

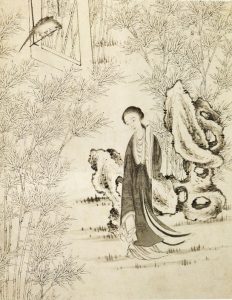

Another common way that Lin Daiyu 林黛玉 is represented is in the company of her parrot. This illustration, from a painting by Gai Qi 改琦, is one example. (It was this series of paintings by Gai Qi which probably provided the basis for the printed collection of illustrations Honglou meng tuyong, which was not published until long after his death.) A key passage in the novel which deals with Daiyu and her parrot is in chapter 35.

Another common way that Lin Daiyu 林黛玉 is represented is in the company of her parrot. This illustration, from a painting by Gai Qi 改琦, is one example. (It was this series of paintings by Gai Qi which probably provided the basis for the printed collection of illustrations Honglou meng tuyong, which was not published until long after his death.) A key passage in the novel which deals with Daiyu and her parrot is in chapter 35.

In the one hundred and twenty chapter version of the novel, Daiyu dies at the precise moment of Baoyu’s marriage with Baochai in chapter 97. Just before her death, she burns her poems, as we see in the painting below, done by Sun Wen 孙温 (c.1817-1903). This scene is also one that attracted the attention of later poets.

The mode of Daiyu’s 黛玉 death is one of the aspects of the ending of the novel which has aroused the most controversy and the most re-telling. David Henry Hwang and Bright Sheng in their 2016 opera have written an ending for Daiyu 黛玉 which is no less tragic than the one in the novel, but is one which shows her as a stronger architect of her own fate.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Much has been written on Daiyu. In addition to Edwards, Men and Women in Qing China, see Waltner “On Not Becoming a Heroine.”

Text from chapter 23 of novel: Daiyu Sweeps Flowers (translation and Chinese text)

Let’s turn to the scene in chapter 23 in the novel; the Chinese original is at the bottom of the page.

Baoyu had been reading Western Chamber, a play with strong erotic overtones.

He had just reached the line “The red flowers in their hosts are falling” when a little gust of wind blew over and a shower of petals suddenly rained down from the tree above, covering his clothes, his book, and all the ground about him. He did not like to shake them off for fear they would be trodden underfoot, so collecting as many of them as he could in the lap of his gown, he carried them to the water’s edge and shook them in. The petals bobbed and circled for a while on the surface of the water before finally disappearing over the weir. When he got back he found that a lot more of them had fallen when he was away. As he hesitated a voice behind him said, “What are you doing here?”

He looked round and saw that it was Daiyu. She was carrying a garden hoe with a muslin bag hanging from the end of it on her shoulder and a garden broom in her hand.

“You’ve come at just the right moment,” said Baoyu, smiling at her. “Here, sweep these petals up and tip them in the water for me! I’ve just tipped one lot in myself.”

“It isn’t a good idea to tip them into the water,” said Daiyu. “The water you see here is clean, but farther on beyond the weir, where it flows on beyond people’s houses, there all sorts of muck and impurity, and in the end they get spoiled just the same. In that corner over there I’ve got a grave for the flowers, and what I am doing now is sweeping them up and putting them in this silk bag to bury them there, so that they can gradually turn back into earth. Isn’t that a cleaner way of disposing of them?”

Baoyu was full of admiration for this idea.

“Just let me put this book down somewhere and I’ll give you a hand.”

“What book?”

“Oh…The Doctrine of the Mean and The Greater Learning,” he said, hastily concealing it.

“Don’t try to fool me!” said Daiyu. “You would have done much better to let me look at it in the first place, instead of hiding it so guiltily.”

“In your case, coz, I have nothing to be afraid of,” said Baoyu, “but if I do let you look, you must promise not to tell anyone. It’s marvelous stuff. Once you start reading it, you’ll even stop wanting to eat.”

He handed the book to her, and Dai-yu put down her things and looked. The more she read, the more she liked it, and before very long she had read several acts. She felt the power of the words and their lingering fragrance. Long after she had finished reading, when she had laid down the book and was sitting there rapt and silent, the lines continued to ring on in her head.

(translation slightly modified from Hawkes, chapter 23)

正看到「落紅成陣」,只見一陣風過,把樹頭上桃花吹下一大半來,落的滿身滿書滿地皆是。寶玉要抖將下來,恐怕腳步踐踏了,只得兜了那花瓣,來至池邊,抖在池內。那花瓣浮在水面,飄飄蕩蕩,竟流出沁芳閘去了。

回來只見地下還有許多,寶玉正踟躕間,只聽背後有人說道:你在這裏作什麼﹖」寶玉一回頭,卻是林黛玉來了,肩上擔著花鋤,鋤上挂著花囊,手內拿著花帚。寶 玉笑道:「好,好,來把這個花掃起來,撂在那水裏。我才撂了好些在那裏呢。」林黛玉道:「撂在水裏不好。你看這裏的水乾淨,只一流出去,有人家的地方髒的 臭的混倒,仍舊把花遭塌了。那畸角上我有一個花塚,如今把他掃了,裝在這絹袋裏,拿土埋上,日久不過隨土化了,豈不乾淨。」寶玉聽了喜不自禁,笑道:「待我放下書,幫你來收拾。」黛玉道:「什么書﹖」寶玉見問,慌的藏之不迭,便說道:「不過是《中庸》《大學》。」黛玉笑道: 「你又在我跟前弄鬼。趁早兒給我瞧,好多著呢。」寶玉道:「好妹妹,若論你,我是不怕的。你看了,好歹別告訴別人去。真真這是好書!你要看了,連飯也不想 吃呢。」一面說,一面遞了過去。林黛玉把花具且都放下,接書來瞧,從頭看去,越看越愛看,不到一頓飯工夫,將十六齣俱已看完,自覺詞藻警人,餘香滿口。雖 看完了書,卻只管出神,心內還默默記誦。

Text from chapter 35 of novel: Daiyu and her Parrot

In chapter 35 of the novel, Daiyu returns home, depressed.

She was about to shed tears once more; but just then her parrot, which had been perched aloft under the verandah leaves, seeing that his mistress had returned, flew down with a sudden squawk that made her jump.

“Wicked Polly,” she said. “You’ve shaken dust all over my head!”

The parrot flew on to its perch. “Snowgoose!” it called. “Raise the blind. Miss Lin is back.”

Daiyu stipped in front of it and tapped its perch. “Did they remember your food and water, Polly?”

The parrot heaved a long sigh, uncannily like the ones that Daiyu was wont to utter, and recited, in its parroty voice:

“Let others laugh flower-burial to see:

Another year who will be burying me?”

Daiyu and Nightingale both burst out laughing.

“It’s what you’re always reciting yourself, Miss,” said Nightingale. “Fancy Polly being able to remember it!”

Daiyu made her take the perch down and hang it up outside the round “moon-window” of her study.

Going indoors she sat down by the moon-window to take her medicine. Light reflected from the bamboos outside passed through the gauze of the window to make a green gloom within, lending a cold, aquarian look to the floor and the surfaces of the furniture. To keep her spirits up in these somewhat cheerless surroundings she spoke teasingly to the parrot hanging on the other side of the gauze until he jumped and squawked on his perch, after which she taught him a few snatches of her favorite poems.

Paul Rouzer talks about Daiyu’s poems on burying flowers

In this video, Paul Rouzer, of the Department of Asian Languages and Literatures at the University of Minnesota, discusses and translates the cycle of poetry that Daiyu writes about sweeping flowers. He is attentive to both meter and meaning. Even if you do not yet know that you are interested in Chinese poetry, you should listen to this lecture.

PDF File: Paul Rouzer talks about Daiyu’s poems This sixteen-page pdf file is the text of Rouzer’s talk.