Jin Yi 金逸: “Written on a Cold Night” 寒夜待竹士不歸讀紅樓夢傳奇有作

The poet Jin Yi 金逸 (1770-1794) was from Changzhou, in Suzhou. She suffered from illness (it is not clear exactly what the illness was) for the entirety of her short life; she died at the age of 25. She was a prolific poet, a disciple of Yuan Mei 袁枚. Yang Binbin has written about the ways in which Jin Yi identified with Lin Daiyu, as a kindred spirit in illness. She wrote the following poem on Honglou meng in 1794, as she was dying.

Written on a Cold Night Waiting for my Husband, who does not Return, and Reading Honglou meng chuanqi

Let us begin with Ellen Widmer’s translation of the poem

Cloudiness pervades the snow with a penetrating chill.

Twisting and turning incense disappears on an agate plate.

I wait for you who’ve not yet returned; then, abandoning my daydream, I get up.

No means to dispel sorrow, I borrow a book to read.Their feelings run extraordinarily deep,

Their souls can hardly stand such exertion; they risk their lives.

Even the toll of tears seems not quite enough.

On second thought, what has this to do with me?

And here is Yang Binbin’s translation of the poem:

The impending snow brings nipping chill;

The incenses, twisting and turning, vanish from the agate plate.

I throw off my dreams and rise from bed, having waited for you;

And read my borrowed book, having no means to dispel my sorrow.How could passion persist with such depth—

Overwhelmed by love [she] would give up even life.

Pearl tears being dried up, [she] still says they are few;

Pondering on all this, I’m amazed how much this has to do with me.

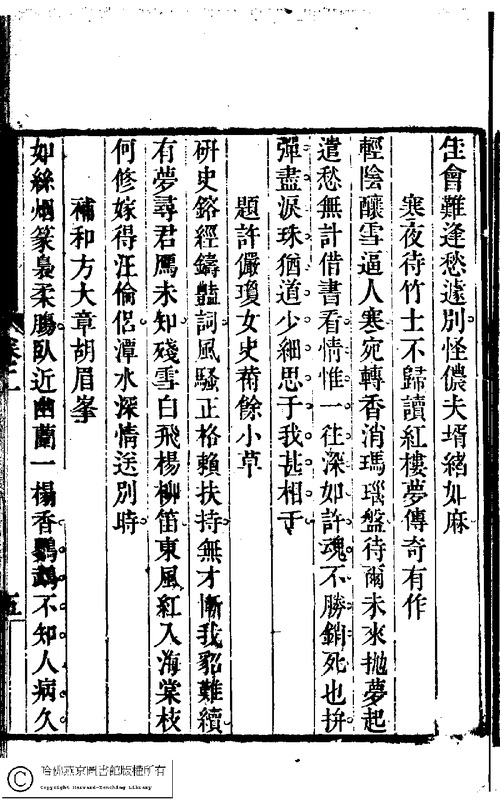

And here is the Chinese text of the poem:

寒夜待竹士不歸讀紅樓夢傳奇有作輕陰釀雪逼人寒,宛轉香消瑪瑙盡,待爾未來拋夢起,遣愁無計借書看。情惟一往深如許,魂不勝銷死也拚,彈盡淚珠猶道少,細思於我甚相干。

Translations of other poems (into German) by Jin Yi, are available here.

Notes on the poem

It is possible that this poem is about a play based on the novel (the chuanqi referred to in the title means play) rather than about the novel itself. (This is unlikely: Ellen Widmer points out that she does not know of any plays that were written this early, and while chuanqi can mean play, it can also refer to a work of fiction.) The poem presents Jin Yi as reading the book casually: she cannot sleep so she picks up a book which she identifies as belonging to her husband. This is reminiscent of how Zhou Qi describes her first encounter with the novel: she happened upon the novel on her husband’s desk. Although the English of the first two stanzas differs considerably, it is clear that the two translators agree on the basic meaning of the first stanza. But this is not true of the second stanza. Widmer translates the third line: “Overwhelmed by love [she] would give up even life,” while Yang’s translation reads: “Their souls can hardly stand such exertion; they risk their lives.” (Here again is the Chinese: 魂不勝銷死也拚. The fact that Widmer reads the subject of the line as singular (and applying only to Lin Daiyu) and Yang regards it as plural (and applying to both Daiyu and Jia Baoyu) is caused by the fact that there is no subject in the Chinese line. Both readings are plausible, but they are very different. The two translators also differ on the third line of the stanza: Widmer translates it “Even the toll of tears seems not quite enough” and Yang translates it “Pearl tears being dried up, [she] still says they are few.” (And here is the Chinese: 彈盡淚珠猶道少.) I am not quite sure how to interpret the first four words of the line: Yang sees the tears as having dried. But I would like to offer a third reading for the ending of the line: 猶道少. I lean toward Yang’s translation, but would say “She still says they are not enough.” You will remember that in the cosmic framing of the novel, the Stone (Baoyu) watered the Crimson Pearl Flower (Daiyu), and as a result she owed him a debt of tears, which she could never repay. I would translate that line something like “Drop after drop, the pearl tears fall; she still says they are not enough.”

But it is the last line of the stanza that sees the sharpest difference. The two translators agree that in that line Jin Yi is stepping back and commenting on the relevance of the story to her own life. Widmer has her saying: “On second thought, what has this to do with me?” This translation suggests that in spite of the identification with Lin Daiyu that we see Jin Yi creating throughout the poem, on second thought, she rejects the identification. Yang translates the same line “Pondering on all this, I’m amazed how much this has to do with me,” which reinforces rather than repudiates the connection between Jin Yi and Daiyu.The Chinese original is 細思於我甚相干. The line is a rhetorical question; both translations are defensible.

Listen to Li Kan read the Chinese original.

Widmer, Beauty and the Book, 141-42; Yang, “Disease of Passion,” 75.

Translations of other poems by Jin Yi are available in Chang and Saussy, 485-17 and (into German) here.