Daily Life in the Novel

The novel is full of information about daily life in eighteenth-century China; in fact some scholars have called it a veritable encyclopedia of information about daily life in eighteenth-century China. It would be an odd encyclopedia, an encyclopedia that is a fictionalized account of the lives of the very rich.

Nonetheless, one can learn much about daily practices from the novel. It is a source of surprising details that one might hard-pressed to find anywhere else.

For example, it is a terrific source about hygiene among the upper classes. We see Baoyu using salt to clean his teeth in chapter 21, and in chapter 27 we see Xifeng “grooming her teeth with an ear-cleaner.” We frequently see people using tea to rinse their mouths. In fact, one of the faux pas that Daiyu commits when she first comes to live with the Jia family is that she does not understand that the first tea brought to her after a meal is for rinsing the mouth, not for drinking.

Maids would bring water and scented soap to the ladies of the house so that they could wash themselves. In chapter 78, we see Aroma sending someone out to get washing water for Baoyu. The early morning toilette in the household seems to have been almost a social occasion. At several points in the novel, we see maids washing their hair (and disputes over who has access to hair washing resources.)

The family is not in perfect health; in fact illness may well be a sign of the impending decline of the family. In chapter 21, Qiaojie, the infant daughter of Wang Xifeng and Jia Lian is diagnosed with smallpox, which was endemic in China at the time. The child is treated with drugs (made of pig’s tail blood and essence of mulberry-worm) but her mother also makes offerings to the Smallpox Goddess. We see a somewhat pedantic doctor called to treat Baoyu in chapter 57 when he becomes delirious at the thought that Daiyu might leave him. In chapter 78 when the illness of Skybright is discussed we are told that the doctor has diagnosed her with “some kind of consumption–a kind that is quite common, apparently, in unmarried girls.” (For more on medicine in the novel, see Schonebaum Novel Medicine. )

The novel is rich in its description of clothing. The Jia family prides itself on its “housemade” clothing, and at several points in the novel, it is stressed that the quality of the workmanship done in the house is far superior to work done outside. The sewing may take place within the household, but there is no evidence that spinning or weaving takes place in the household. Bolts of fabric are often given as gifts.

We gain some insight into marriage negotiations (and scorn of people who pay attention to finances when they negotiate dowry and bride price) when Aunt Xue’s nephew Xue Ke is betrothed to Xing Xiu-yan in chapter 57.

We do see people other than the Jias. For example, early in the novel, when Zhen Shiyin disappears, his wife returns to live with her parents. We are told “by sewing and embroidering morning, noon and night, she and her women were able to make some contribution to her father’s income.” (chapter 1) We also see silk sellers coming to the door of the Zhen household, and maids buying silk (also in chapter 1.)

The novel is explicitly interested in distancing itself from the market. When Baoyu damages a rare Russian peacock feather cape that Granny Jia had lent him, the servants send it out and look for an “invisible mender” to repair it. None of the local invisible menders are willing to take it on, because they were unfamiliar with the materials. A maid in the Jia household, Skybright, undertakes to mend the cape. She must work all night to complete the task, but she succeeds, and Granny Jia never learns of the mishap.

We see casual references to city walls and the closure of city gates: in chapter 2, Zhen Yucun casually comments “We must be careful not to get shut out of the city.” In spite of the seclusion of the women in the Jia family (and Baoyu) we get a lively picture of street life just outside the household gates. For example in chapter 6, we see toy vendors and sweetmeat sellers congregating at the door–and children crowding around the toy vendors.

Although many members of the Jia family were highly literate, the Jia family had a professional letter writer in their employ; the novel also refers to letter-writers who could be found on the streets. This underscores the importance of the written word in Qing China; the written word mattered even to people who were not themselves literate.

Where does money come from?

At the opening of the novel, the Jia are fabulously wealthy. It is not clear where their money came from: family members have, for generations, been officials. But rents from land are also an important source of wealth; we see the process of collecting rent from tenants when Wang Xifeng takes over household management. During the course of those episodes, it becomes clear that Xifeng is corrupt.

The family of Baochai, the Xue, are also fabulously rich, and we do know where their money comes from. It comes from pawnshops. While it might be an exaggeration to say that Aunt Xue (Baochai’s mother) and Baochai were embarrassed by the source of their wealth, it is true that they suffered from what we might term status anxiety.

The financial arrangements within the household are complex. The matriarch, Granny Jia, has her own stash of money, which Xifeng assumes will be used to pay the dowry for Baochai and the brideprice for Baoyu. (The marriage system in Qing China had both brideprice, a sum of money or goods which the groom’s family paid the bride’s family, and dowry, goods, money, and rarely land which the bride took into the marriage. The dowry normally came from her natal family, but a wider circle of kinsmen and even friends might contribute to the dowry.) The Jia family calculates that the dowries for daughters will come to seven or eight thousand taels, while the brideprice for Jia Huan (Baoyu’s younger half brother) will come to only three thousand (chapter 55). We see Grandmother Jia withdrawing funds from her own stash on numerous occasions–in chapter 22 she takes 20 taels of silver “from her private store” to pay for a celebration for Baochao’s fifteenth birthday. When Xifeng hears that Grandmother Jia wants plays performed at the party, she insists that Grandmother Jia pay for the performances–“She’s going to have to cough up something out of those private savings of hers she has been hoarding all these years” (ch.22).

People within the household receive an allowance; if they want special food from the kitchen, they are expected to pay the cook a little extra. Thus there is a way in which family transactions are monetized in the novel. When Tanchun wants to host a party in honor of Patience’s birthday, she asks Cook Liu to prepare the feast and then send her the bill (ch.62). Aroma collects funds for a party from the maids (ch.63).

When the acting troupe is disbanded, the young actresses who chose to stay with the family were assigned a “foster-mother” given a small allowance, which seems to have been given over to the foster-mother. This exacerbates the tension between Parfumee and her foster-mother in chapter 64.

Xing Xiuyan is a poor relation whose allowance is not adequate; she pawns warm clothing. Baochai offers to help her out, and when she asks for information bout the pawnshop, she discovers that it is a shop owned by her family (ch.57). This disclosure does not seem to embarrass Baochai, but it does embarrass Xiuyan. When Xiuyan reveals the pawn ticket, it becomes clear that Daiyu has no idea what it is. The elder women in the family do know what it is (ch.57).

One of the major plotlines is the decline of the once-prosperous Jia household. The decline is both moral and financial; money and morals are intertwined.

Clothing in the novel

“Objects remind us,” so the maid Ripple reminds the reader, citing a proverb in chapter 78.

Clothing is never just clothing in Dream of the Red Chamber. When Daiyu first sees Baoyu, she notices in great detail what he is wearing. Often when a character appears, we are told in great detail what he or she is wearing. (Interestingly, Daiyu is in general an exception to this; we are told very little about her clothing.)

Cao Xueqin’s 曹雪芹 grandfather, Cao Yin, was Textile Commissioner, and some have speculated that his great love of fabrics came from that family tradition.

Most of the Jia family clothing was made within the household–we frequently see both the young women and maids sewing. We are told in chapter 77 that one of the things that keeps Aroma busy is that she organizes the sewing and the other work of the maids. It is less clear where the cloth comes from. There seems to be no textile production within the household. (There is one mention of a maid spinning.) While we see other households buying textiles from merchants on the street, there is very little evidence that the Jia purchased fabric that way. Indeed, fabric seems to come from the vast Jia storehouses–when someone needs fabric, they are sent to the storehouse.

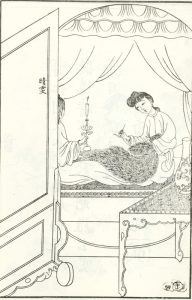

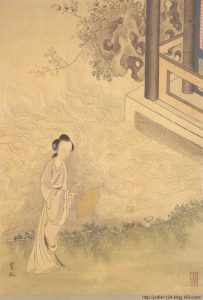

Rare garments play an important role in the plot. Baoyu is given a rare Russian cape made of peacock feathers by Grandmother Jia. On first wearing it, he burns a small hole in it. He asks servants to find someone on the outside to mend it. The servants tried many craftsmen, including some with the promising name of “invisible menders” but could not find anyone who was willing to undertake the task of mending such a rare and precious garment. So the maid Skybright is given the task of mending the garment, even though she is quite ill. She sits all night mending the cloak. The iconic representation of Skybright is of her mending the cloak.

When the Jia household is raided near the end of the novel, clothing that was restricted to the imperial court was found. Qing China had strict sumptuary regulations–one could tell by a quick look at a man in official regalia exactly what his rank was, and one could frequently tell the rank of a man by looking at his wife. One of the charges brought against the family was that they had garments which were not appropriate to their station in life. (Sumptuary regulations were often violated; the violations of the Jia family were not unique, though they may have been excessive.)

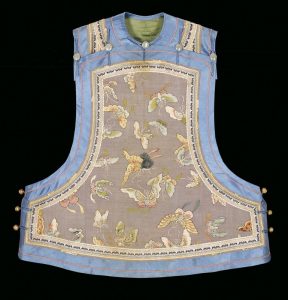

Butterfly Vest

This lovely butterfly vest, probably made in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, is held at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. It is woven, rather than embroidered, using a technique known as kesi, which is more or less like the technique used to make tapestry. If you zoom into the image available at this link, you will be able to see that the front of the vest is pieced together in three panels–a main panel with two side panels.

This lovely butterfly vest, probably made in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, is held at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. It is woven, rather than embroidered, using a technique known as kesi, which is more or less like the technique used to make tapestry. If you zoom into the image available at this link, you will be able to see that the front of the vest is pieced together in three panels–a main panel with two side panels.

In the accompanying video, Ann Waltner, Kathleen Ryor and Karil Kucera examine two pieces of clothing from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts: a theatrical robe and the vest picture above. In the video we discuss the particular significance of clothing in Qing elite culture. One of the things we stress in the video is that butterflies appear only on women’s clothing. It is a statement we are in general willing to stand by–but at several points in the novel, Baoyu wears clothing with butterflies on it. This of course stresses the feminine side of Baoyu’s nature.

In the video, Kathleen Ryor refers to an article by John Hay which talks about the sensuous nature of fabric. The full reference to the article is “The Body Invisible in Chinese Art?” and it appears in Angela Zito and Tani Barlow, Body, Subject and Power in China, University of Chicago Press, 1994. We also discuss the story of Liang Shanbo 梁山伯 and Zhu Yingtai 祝英台 , two lovers who were reunited in death as butterflies. A key play which talks about them has been translated by Wilt Idema, under the title The Butterfly Lovers. We also refer to the novel Jin Ping Mei, which exists in a fine translation by David Roy called The Plum in the Golden Vase.

And of course, when we speak of butterflies in the context of the Dream of the Red Chamber, we come back to Baochai, and the iconic scene where she is chasing butterflies.

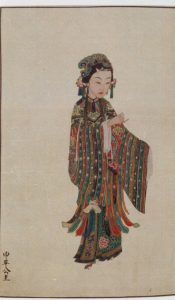

Theatrical costume

When Kathleen Ryor, Karil Kucera and I were at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, we examined the spectacular robe pictured above. We had asked the museum to show us a woman’s embroidered garment, and this was what they brought us. We were interested in exploring the difference between embroidery and other kinds of textile patterning, such as kesi (a technique more or less like a delicate tapestry), used on the butterfly vest which we presented earlier in this section. As it will become clear to you as you watch the video, we were somewhat perplexed by what we saw. It was clearly a wedding robe (and is labeled as such on the museum’s website), but it was worn in a way which showed substantial wear. As I end the video, I articulate our perplexity by talking about the mystery of the object.

When Kathleen Ryor, Karil Kucera and I were at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, we examined the spectacular robe pictured above. We had asked the museum to show us a woman’s embroidered garment, and this was what they brought us. We were interested in exploring the difference between embroidery and other kinds of textile patterning, such as kesi (a technique more or less like a delicate tapestry), used on the butterfly vest which we presented earlier in this section. As it will become clear to you as you watch the video, we were somewhat perplexed by what we saw. It was clearly a wedding robe (and is labeled as such on the museum’s website), but it was worn in a way which showed substantial wear. As I end the video, I articulate our perplexity by talking about the mystery of the object.

As we were admiring the gown, one of the things we wished we could see was the gown on a woman. We imagined how it might flow and flutter when she moved. One of the images in the Zeitlin and Li book is a woodblock print of an actress wearing such a gown (shown on the left), a print which suggests something of the gown in motion.

As we were admiring the gown, one of the things we wished we could see was the gown on a woman. We imagined how it might flow and flutter when she moved. One of the images in the Zeitlin and Li book is a woodblock print of an actress wearing such a gown (shown on the left), a print which suggests something of the gown in motion.

This episode, which began with our wonder at the splendor at the gown, but our confusion at what it might have been used for, was resolved by comparison to another image. The mystery vanished; museum staff and my art historian colleagues quickly agreed that the garment had to be a theatrical costume. In some small way, this is how research is done–you see something you don’t quite understand, you speculate about what it might be, you keep on looking for answers, you find what seems to you to be a reasonable answer, and you consult with experts to see if your answer is on track.

So while we have figured out what the gown was, it still retains many mysteries. Who was the actress who wore it? What were the plays she performed in? Who was in the audience? Who was the artist who made it? The gown provides rich ground for speculation.

Theatrical performance in Dream of the Red Chamber

Drama plays a very important role in the novel. Operas were a favored form of entertainment at birthday parties and other special events, as we see in the celebration of Baochai’s fifteenth birthday in chapter 21. When Grandmother Jia meets two of the female actors who particularly charm her, she learns that “the leading lady turned out to be eleven and the clown only nine.” (Because the years are calculated in sui, the children could have been a year or so younger.)

The Jia family later purchased a resident troupe of female actors.

The presence of house theatrical troupes had significant consequences in terms of elite female audiences for drama. Women of the elite were restricted to the inner quarters of their homes. (In the case of the Jia family, those inner quarters could be quite capacious.) But nothing prevented women from attending theatrical performances in their own homes. (It is true that some critics of the novel objected to the fact that men and women mingled while watching drama.)

The young actors and actresses from the theatrical troupe were a complicated presence in the household.

Food in the Novel

Food plays an important role in Honglou meng. Eating is a social activity; there are elaborate banquets and there are intimate snacks. The food for the household is provided by a kitchen staff, who are (normally) adept at providing the members of the household with the food they desire. Food is also important in the politics of the household: who gets what delicacies shows who has what power.

A number of incidents in the novel show the emotional significance of food. One such incident occurs when Baoyu holds back a snack of koumiss for his maid Xiren (Aroma in the Hawkes translation). His wetnurse, Nanny Li, sees the koumiss and eats it. It is only Aroma’s deft handling of the situation that averts a crisis.

In another incident, Chess has sent her maid Lotus to ask for eggs for dinner. Cook Liu responds with anger; she views the request as excessive. Her response illuminates the finances of food in the Jia household. Cook Liu provided the residents of the garden with a base level of food, but she expected those who made extra demands to pay for them out of their allowances. Her tirade, reproduced below, tells us much about hierarchy and finances in the novel.

Food could be a special gift–as the lychees presented to Tanchun on a black onyx saucer in chapter 37. In the same chapter, Aroma sends Shi Xiangyun foxnuts and caltrops and chestnut fudge, a delicacy made of chestnut puree steamed with cassia-flavored sugar. Aroma noted with pride that the delicacies she was sending were either grown in the household garden or made from things that were grown in the garden.

The Chinese Television Network CCTV 4 ran a series of television shows which demonstrate to viewers how to make food which is featured in the novel. The segment is part of a larger series on Chinese medicine. (In traditional Chinese medicine, diet is regarded as crucial to the health of the human body.) The segment below is subtitled in English.

The series has a number of other episodes which are not subtitled in English, though they are captioned in Chinese, which are available here.

Cook Liu

In chapter 61, the maid Lotus makes what Cook Liu regards to be an outrageous request for eggs for dinner for her mistress Chess. Cook Liu responds:

“Holy name” said Cook Liu. “These people here will be my witness. Whenever anyone from any of the other apartments, whether mistress or maid asks me for a special order–and I’m not just talking about that occasion you mentioned, I’m talking about ever since this kitchen here first started–they invariably offer me something to cover the extra cost. Whether I have to buy something extra or not, it’s a nice gesture and I appreciate it. Some people think that as I only have the young ladies to cater to, I must make a lot out of it; but if anyone took the trouble to sit down and work it out, they’d get a shock. Between forty and fifty people I have to cater for, counting both mistresses and maids. And do you know what my allowance is? Two chickens, two ducks, ten catties of pork and a thousand cash worth of vegetables. You try managing on that! I can barely make it stretch to two meals a day provided everyone sticks to the regular menu; but if I’m going to have one person ordering one thing and one person ordering another, turning down the food I’ve bought for them and expecting me to buy other materials to make up their orders, my allowance simply won’t stretch to it. If that’s the way you want it, you’ll just have to ask Her Ladyship to give you all bigger allowances; then we can do what they do in the main kitchen for Her Old Ladyship’s meals; have a blackboard with the names of all dishes under the sun chalked up on it and work through them one by one, having a different dish every day. Then you could settle with me for what you’d eaten at the end of each month. A month or two ago Miss Tan [Tanchun] and Miss Bao [Baochai] suddenly thought they’d fancy a dish of salted bean sprouts and Miss Tan sent one of the girls over with five hundred cash to ask me if I would prepare it for them. I laughed. “They’d never eat five hundred cash worth,” I said, “not if they had bellies like the Laughing Buddha. Twenty or thirty cash would be ample.” I sent the money back to her, but she wouldn’t take it,–said I should keep it to buy myself a drink with. “Now that the kitchen’s inside,” she said, “I expect you often have people coming round and asking you for favors.” She said, “I know it’s hard for you to refuse them, but even salt and soy sauce cost something, and we don’t want you to end up out of pocket. Let’s call this a payment to make up for some of the extras that other people have had out of you.” Now, there’s a kind, understanding young lady! I pray to the Lord in my heart for a young lady like that! Too bad that Mrs. Zhao got to hear about it. She was furious of course, thought I was doing far too well out of it. And sure enough she sent one of her little maids round less than ten days later asking for this and asking for that. I couldn’t help laughing. You’re just the same, I suppose you’ve taken a leaf out of her book. Well, it’s no good. My allowance just won’t stretch to it. ”

Notes on the passage: Mrs. Zhao is married to Jia Zheng as a concubine, and is the mother of Jia Huan and Tanchun. She is constantly aware of her inferior status in the household.

Text from chapter 61: (Chinese) Cook Liu Explains Kitchen Economics

阿彌陀佛!這些人眼見的!別說前日一次,就從舊年以來,那屋裡,偶然間,不論姑娘姐兒們,要添一樣半樣,誰不是先拿了錢來另買另添?有的沒的,名聲好聽。算著連姑娘帶姐兒們四五十人,一日也只管要兩隻雞,兩隻鴨子,一二十斤肉。一吊錢的菜蔬,你們算算,夠做什麼的?連本項兩頓飯還撐持不住,還擱得住這個點這樣,那個點那樣?買來的又不吃,又要別的去!--既這樣,不如回了大太:多添些分例,也像大廚房裡預備老太太的飯,把天下所有的菜蔬,用水牌寫了,天天轉著吃,到一個月現算倒好!連前日三姑娘和寶姑娘偶然商量了,要吃個油鹽炒豆芽兒來,現打發個姐兒拿著五百錢給我,我倒笑起來了,說:『二位姑娘就是大肚子彌勒佛,也吃不了五百錢的。』這二三十個錢的事,還備得起,趕著我送回錢去,到底不收,說賞我打酒吃。又說:『如今廚房在裡頭,保不住屋裡的人不去叨登。一鹽一醬,那不是錢買的?你不給又不好,給了你又沒的賠,你拿著這個錢,權當還了他們素日叨登的東西窩兒。』這就是明白體下的姑娘,我們心裡,只替他念佛。沒的趙姨奶奶聽了,又氣不忿,反說太便宜了我,隔不了十天,也打發個小丫頭子來尋這樣,尋那樣,我倒好笑起來。你們竟成了例,不是這個,就是那個,我那裡有這些賠的!

The Chinese text project, which has the text online with a dictionary behind it, is here.

http://ctext.org/dictionary.pl?if=en&id=105399

The novel is rich in descriptions of rituals and ceremonies, such as funerals and birthday celebrations. In this blog post, Stephen Jones analyzes some of the rituals in the novel.