Cousins in the Garden

The plot of Dream of the Red Chamber depends on the three young cousins, Baoyu, Daiyu and Baochai, living in close proximity to one another in a sumptuously elegant garden. Domestic space in China is normally conceptualized as an inner realm (which is female space) and an outer realm (which is male space). Scholars such as Keith McMahon and Maram Epstein have noted that gardens in late imperial Chinese fiction are often seen as dangerous, in-between sorts of places. Their in-betweenness facilitates transgression.

The plot of Dream of the Red Chamber depends on the three young cousins, Baoyu, Daiyu and Baochai, living in close proximity to one another in a sumptuously elegant garden. Domestic space in China is normally conceptualized as an inner realm (which is female space) and an outer realm (which is male space). Scholars such as Keith McMahon and Maram Epstein have noted that gardens in late imperial Chinese fiction are often seen as dangerous, in-between sorts of places. Their in-betweenness facilitates transgression.

How did it come about that adolescent cousins are living in an idyllic garden, a boy with girls, with a minimum of adult supervision? And how is it that the cousins are seen as possible marriage partners?

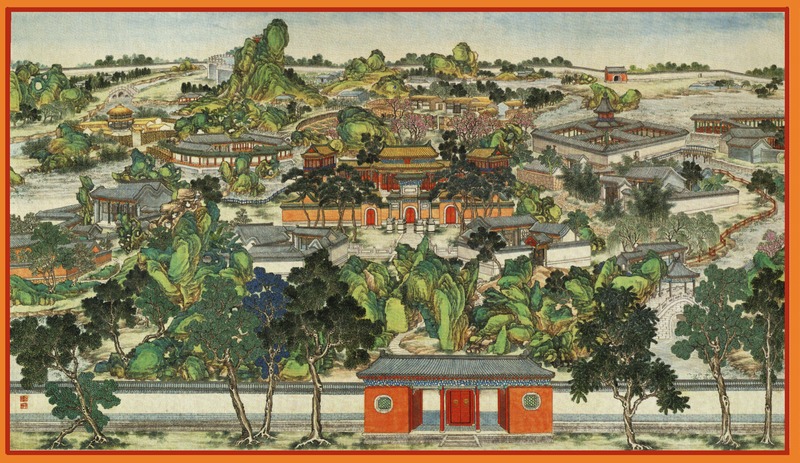

First, the garden. The garden which is the site of so much of the action of the novel was not constructed until chapter 17, when Yuanchun), the daughter who has become an imperial concubine, returns home for a brief visit. The Jia family has spent lavishly on the garden. Some interpreters of the novel have suggested that the experience of the author’s grandfather Cao Yin, in arranging the southern tours of the Kangxi emperor (and in hosting the emperor as he visited Suzhou) might have influenced the description of the garden in the scenes of Yuanchun’s visit home. While it is hard to know precisely how the family experience of Cao Xueqin influenced these passages, there is no doubt that these passages portray her homecoming as a royal excursion, not simply a daughter returning home.

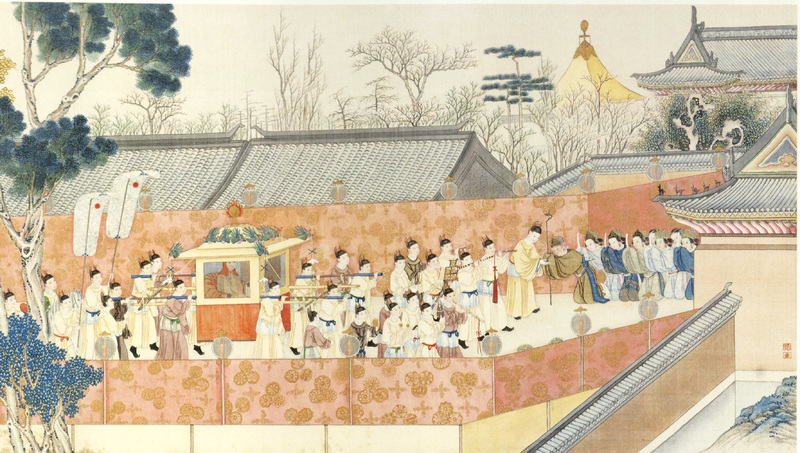

Yuanchun’s homecoming is portrayed in this painting by Sun Wen (1818-1904). We see Yuanchun in a sedan chair, accompanied by her entourage. Members of her family stand outside the gate, bowing to the young woman, their kinswoman, the royal concubine. The scene is described in chapter 18 of the novel.

The novel describes Yuanchun’s visit as follows:

Yuanchun’s homecoming in David Hawkes’ translation (chapter 17)

Suddenly, as afternoon drew toward evening, a clatter of many hooves was heard, and after a short pause, a group of ten or so eunuchs rushed in, out of breath, clasping their hands as they ran. This was taken by the other eunuchs as a sign that the Imperial Concubine was on her way, for they at once jumped up and hurried to their prearranged places. The family, too, took up their prearranged positions once more, Jia She and the menfolk outside the west gate and Grandmother Jia with the ladies outside the main entrance.

For a long time there was total silence. Then a couple of eunuchs on horseback came riding very, very slowly up to the west gate. Dismounting, they led their horses out of sight beyond the cloth screens, then returned to take up their stand at the sides of the road, half-facing toward the the west. After considerable wait, two more eunuchs arrived and went through the same motions as the first pair. Then another two, and then another, until in all some ten pairs were standing at the sides of the road, their faces turned expectantly toward the west.

Presently a faint sound of music was heard and the Imperial Concubine’s procession at last came in sight.

First, came several pairs of eunuchs carrying embroidered banners.

Then, several more pairs with ceremonial peasant-feather fans.

Then eunuchs swinging gold-inlaid censers in which special ‘palace-incense’ was burning.

Next came a great gold-colored ‘seven-phoenix umbrella of state,’ hanging from its curve-topped shaft like a great drooping bell-flower. In its shadow was borne the Imperial Concubine’s traveling wardrobe: her head-dress, robe, sash and shoes.

Eunuch gentlemen-in-waiting followed carrying her rosary, her embroidered handkerchief, her spittoon, her fly-whisk, and various other items.

Last of all, when this army of attendants had gone by, a great gold-topped palanquin with phoenixes embroidered on its yellow curtains slowly advanced on the shoulders of eight eunuch bearers.

As Grandmother Jia and the rest dropped to their knees, eunuchs rushed up and helped them to get up again. The palanquin passed through the great gate and made for the entrance of a courtyard on the east side of the forecourt. The eunuch knelt beside it and invited the imperial concubine to descend and “change her clothes.” The bearers carried it through the entrance and set it down just inside the courtyard. The other eunuchs then withdrew, leaving Yuanchun’s ladies-in-waiting to help her from the palanquin.

The courtyard she now stepped out into was brilliant with colored lanterns of silk gauze cunningly fashioned in all sorts of beautiful shapes and patterns.

Notes on the text:

What Hawkes translates as “rosary” is not the Catholic rosary at all, but rather a set of Buddhist prayer beads.

And “changing one’s clothes” is a euphamism for using the toilet.

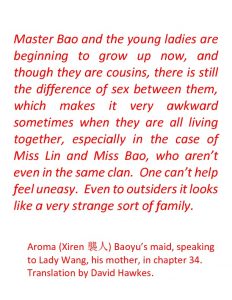

Yuanchun protests the extravagance of the expenditure on her visit home, in both the opera and the novel. After Yuanchun returns to the palace, she decides that it would be wasteful not to use the splendid garden, and so she asks that the girls of the family be allowed to live there. But what to do about Baoyu? Men and women in elite Qing households were to live in separate quarters: the women’s quarters were known as the inner quarters. Young male children resided in the inner quarters with their mothers. But by puberty, a boy should have moved outside and begun to establish himself in the world of men. Yuanchun knows this, of course. But as she ponders the situation, she thinks, “He was different from other boys. If he were not allowed into the garden as well, he would consider himself left out in the cold, and his distress would cause his mother and grandmother to feel unhappy too.” (ch.23) Her instructions are in the form of an edict, an imperial order which cannot be defied, a point which commentators have underscored. So Baoyu lives in the garden with girls, violating gender norms but obeying imperial orders. As his wise and loyal maid Aroma notes, “Even to outsiders it looks like a very strange sort of family.” (ch.34)

It may be a strange sort of family, but it is a family. The girls who are Baoyu’s garden-mates are his cousins. Daiyu’s mother is Baoyu’s father’s sister, and Baochai’s mother is Baoyu’s mother’s sister. To a modern western reader or viewer this may seem strange–would not marriage among the cousins not be incestuous? But the rules which define kin relations and their significance vary from culture to culture. Chinese legal and ritual texts outlined with great precision who would and would not be an appropriate marriage partner: the prohibition of incest was a significant concern in these texts. Kinship in Qing China was traced through the male line and surname was the marker of kinship. Thus while there was no prohibition of marriage of cousins of a different surname, marriage of cousins with the same surname was strictly prohibited. Thus Jia Baoyu, from the standpoint of law and ritual, would have been perfectly able to marry either Lin Daiyu or Xue Baochai. The problem of the novel is which one of them he should in fact marry.

For another visual representation of the garden, see this image, published in a 1908 edition of the novel.

Subtle eroticisms

The three quotations to the left form a starting point for a discussion of love and marriage in the Dream of the Red Chamber. The first quotation comes from Baochai, in act one scene three of the opera by David Henry Hwang and Bright Sheng. It is echoed by the second statement, by the scholar Susan Mann, in an essay entitled “Grooming a Daughter for Marriage.” The statements by Baochai and Mann present marriage in eighteenth-century China in parallel terms. Marriage is both a contractual relationship between two families and a woman’s only hope of happiness (Baochai) or success (Mann).

The three quotations to the left form a starting point for a discussion of love and marriage in the Dream of the Red Chamber. The first quotation comes from Baochai, in act one scene three of the opera by David Henry Hwang and Bright Sheng. It is echoed by the second statement, by the scholar Susan Mann, in an essay entitled “Grooming a Daughter for Marriage.” The statements by Baochai and Mann present marriage in eighteenth-century China in parallel terms. Marriage is both a contractual relationship between two families and a woman’s only hope of happiness (Baochai) or success (Mann).

But Baoyu presents a very different view of marriage in chapter 81 of the novel. He is lamenting the particular fate of his cousin Yingchun, who is married to a man who turns out to be a brute. Baoyu generalizes from her specific experience to a general condemnation of the institution. His gloomy view of marriage is the other side of the statements by Mann and Baochai. If marriage is the source of happiness and the ladder of success, then if a marriage fails, a woman has little or no way out. It is not just the unhappy marriage of Yingchun that makes Baoyu unhappy about marriage: in chapter 58 he says, “People had to marry, of course: they had to reproduce their kind. But what a way for a lovely young girl to end.” In the next chapter, the maid Swallow quotes him as saying “A girl before she marries is a priceless pearl but once she marries the pearl loses its lustere and develops all sort of disagreeable flaws,and by the time she’s an old woman, she’s no longer like a pearl at all, more like a boiled fish-eye,” This anti-family position articulated by Baoyu is as radical as his refusal to study for the civil service exams; both bespeak a refusal to participate in the life that is expected of him.

An aura of incipient sexuality hangs over the adolescents in the garden. They are on the brink of adulthood. In planning a birthday party for Baochai in chapter 22, Wang Xifeng foregrounds Baochai’s in-between status, saying, “she is neither a grown up or exactly a child, either.”There are a number of clues that, while this is in some ways a novel whose plot revolves around the choice of a mate, marriage will not be the happy ending.

Baoyu has had his first sexual experience in the dream in chapter 5. Shortly after he awakes, he shares with his maid Aroma “the lesson he had learned from Disenchantment,” the ethereal creature who had seduced him in his dream (chapter 6). But in many ways Baoyu remains sexually unaware despite his sexual initiation. Aroma is a maid, not a potential marriage partner; sexual relations with her are without serious consequences for him, no matter what the consequences might have been for her.

Baochai and Daiyu both know that their futures hinge on whom they will marry, and for neither of them is there a serious contender other than Baoyu. (Although it would have been possible for Baoyu to marry two women, one of them would have been the principal wife and one would have been a concubine. In some sequels to the novel, Baoyu does marry both women. In order for this to happen, of course, Daiyu must return to life. But that is a story for another page.) While the sensuality of the novel is muted and well-behaved (especially if one compares it to the portrayal of sexuality of the sixteenth-century novel, Jin Ping Mei) it is nonetheless present.

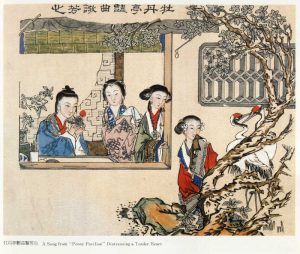

One of the ways this incipient sexuality is expressed is through literary allusion. (This is, after all a Qing dynasty literati novel.) Allusions to several plays with erotic content, notably Peony Pavilon and Romance of the Western Chamber, intensify Daiyu’s anxiety about her status as an orphan who has no one to negotiate her marriage. When Daiyu uses lines from these plays in a drinking game, Baochai reprimands her, saying that such plays were not fit reading material for a proper young lady.

In spite of the fact that these plays were slightly scandalous, both of which were performed at the Jia house. (Well-to-do families would hire theatrical troupes to perform plays on special occasions. Some families, like the Jias, had in-house troupes who regularly performed. Performances in the domestic realm were one of the main ways that elite women, whose movements outside the household were somewhat restricted, saw plays.)

The fact that these plays were regarded as scandalous yet were performed could be regarded as an example of hypocrisy. Or we could interpret it as reflecting a fundamental difference between the play as performed and as read. A performance was a public, social, chaperoned occasion. Furthermore, because plays were extraordinarily long (it was not unusual for a play to have 50 or so acts), they were rarely performed in their entirety. Instead, favorite scenes from the play were performed. Reading was a solitary experience, and hence the words on the page were much more likely to enter into the imagination of a susceptible young person. When Daiyu first reads Peony Pavilion, in chapter 23, the narrator tells us that “she felt the power of words and their lingering fragrance…”

Paul Rouzer’s discussion of Dai-yu’s poetry on burying flowers shows ways in which her imagination is not constrained by conventional morality, despite her identity as a young woman of the upper classes.

Not-so-subtle sexual scandal

While sexuality among the cousins in the gardens is expressed elegantly–through poetic references, for example, other episodes of sexual activity are portrayed as being crude or dangerous or sometimes both. The sexual appetites of men in the Jia household other than Baoyu are at times portrayed as excessive and immoral. And the sexual activity of unmarried servants, even when consensual, threatens to the social order of the household.

The excessive sexuality of the Jia men is treated at some length. When his wife Wang Xifeng is required to sleep separately from him because her sexual abstinence was part of the treatment for her daughter’s smallpox, Jia Lian “was reduced to slaking his fires on the more presentable of his pages” Ich.21). But he shortly finds another sexual partner, an attractive young servant who was amenable to male charms, which earned her the nickname of “the Mattress.” Later in the novel, Jia Lian becomes infatuated with You Erjie, and takes her as a concubine, setting her up in a separate residence without telling his wife Wang Xifeng. When Wang Xifeng discovers the marriage, she takes her revenge on Erjie. Jia Rui’s infatuation with Wang Xifeng ends with his death. Jia She’s desire for Faithful is thwarted only because she has powerful patrons among the women of the household. And so on.

The sexuality of servants, especially servant girls, is of some concern in the novel. Skybright is expelled because Lady Wang and Grandmother Jia suspected that she had (or would) seduce Baoyu. She is not in good health when she is expelled, and she dies shortly after. Chess (Siqi) has an affair with her cousin, is expelled from the household and kills herself. There are other examples, some of which are recounted in the section on Servants in this PressBook.

There is also a sense throughout the novel that sex presents a danger to young women. In the very first chapter of the novel, Yinglian (the daughter and only child of Zhen Shiyin) is kidnapped. We are told that “This type of kidnapper specializes in kidnapping very young girls and rearing them until they are twelve or thirteen for sale in other parts of the country.” We hear Yinglian’s story through her own words in chapter 4. Xue Pan (the brother of Xue Baochai) decides that he needs to posess her, and kills a man in a dispute over her purchase. Dealing with the murder charges against Xue Pan is a constant worry to Aunt Xue and Xue Baochai. The murder itself, committed in the context of purchasing a slave for sexual purposes, casts a pall over the whole novel. The sordid sexual escapades of Xue Pan serve as a foil to the delicate sexuality in the garden. Yinglian later takes the name of Caltrop, and joins the Jia household as Xue Pan’s concubine (or, in David Hawkes’ translation, chamber wife.)

These episodes of sordid sexuality can be seen as a foil to the pure passion (qing) that the Stone and the Crimson Pearl Flower have come to earth to explore.