ZHOU QI 周綺 COLOPHON ON WANG QIAO 汪喬 PAINTING

Listen here to a recording of Li Kan reading the colophon in Chinese

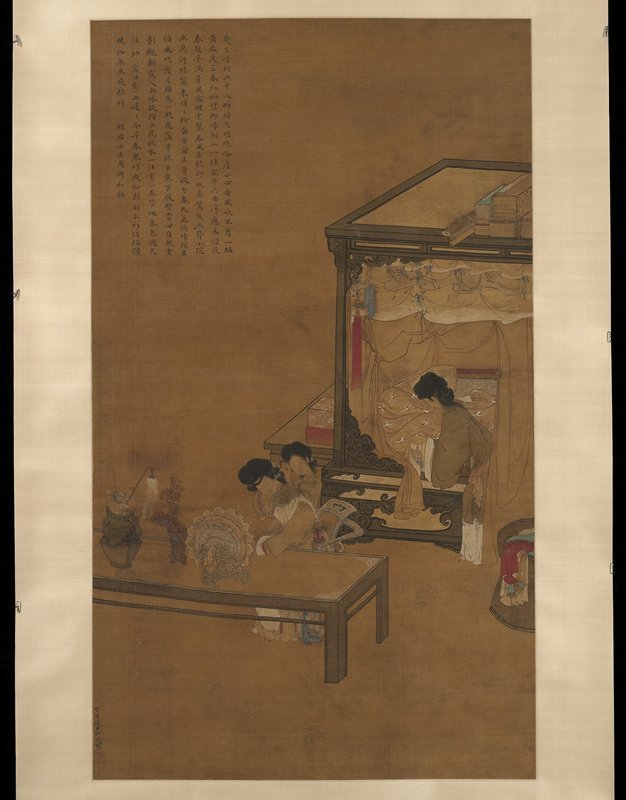

Zhou Qi 周綺 composed a colophon on a 1654 painting by Wang Qiao 汪喬, “A Woman at her Dressing Table,” which is held by the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. If you follow this link, you will be led to a zoomable photograph of the image on the website of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. If you read Chinese, look carefully at the bottom of the colophon. You will find the words 初稿 chu gao, which literally mean “first draft.” The painting was about 150 years old when she inscribed the colophon on it; Zhou Qi 周綺 was clearly not using it for calligraphy practice. It is likely that the phrase is a polite deprecatory phrase, to discount the labor and the skill that went into the making of the colophon. We should not over-read this; deprecatories were commonly used by both men and women in Qing China. Nonetheless, it is unusual to see the phrase “first draft” attached to a colophon. We should remember the way Zhou Qi 周綺 talks about how she first encountered the novel–it was lying on her husband’s desk and she casually picked it up.

Here is a transcription of the colophon:

幾生修到畫中人 柳暗花明絕俗塵

廿四番風吹不著 一編黃卷度三春

紅桃碧柳傍湖山 一抹闌干六曲灣

應為惜花春起早 滿身風露理雲鬟

春風柔較柳絲柔 鶯燕無聲小院幽

莫訝綠鬢來悄悄 粉奩香盒未曾收

今春天氣總晴陰 生怕風吹愛月臨

為一瓶花簾半捲 乍寒乍暖替當心

自然雲影襯朝霞 人面休疑陌上花

秋水一汪書一卷 管他春色編天涯

紗窗日影上遲遲 今早春寒昨夜知

斟酌衣衫須稱體 曉妝無異晚妝時

And here is a translation:

How many lives did it take you to become a person in this picture?

Willows are dark, flowers are bright; they are like nothing else in this dusty world.

The fragrant wind from the twenty-four bridges cannot reach her.

With one scroll of yellow text she passes the springtime of her youth.

Red peaches and green willows by the lakes and mountains.

One stretch of balustrade with six bends.

It must be for the love of flowers that she rises early this spring.

Enshrouded in wind and dew, she tidies her cloud-like hair.

The spring wind is gentler than willow floss,

Orioles and swallows make no sound; the small courtyard is quiet.

Do not be surprised that the servant arrives noiselessly.

The cosmetics case and the incense box have not yet been packed away.

This spring the weather is unpredictably cloudy.

She fears the wind blowing but loves the coming of the moon,

For one vase of flowers, she rolls up the curtain.

[The weather] being by turns cold and hot, I worry about them.

In all naturalness, the shadows of clouds frame the morning glow.

Do not mistake her face for the flower by the wayside.

One deep gaze from her eye, one scroll of books.

Why care about spring spreading to the ends of the earth.

On the gauze windows, the sun’s shadows rise slowly.

This morning’s spring chill–you knew about it last night.

Choose your clothes carefully–they have to fit your person.

Your morning toilette is no different from the evening one.

Translation modified slightly from Widmer, Beauty and the Book, 198-99.

Notes on poem: In line 2, the word 暗 an means dark in the sense of dim or concealed; the willows are a sharp contrast with the bright flowers. The phrase translated “the dusty world” is su chen 俗塵. Su 俗 means secular, as opposed to sacred, and chen is often used in Buddhist texts to mean the mundane world. Thus the willows and flowers the poet is talking about are not part of the mundane world. In line 3, Widmer glosses the phrase “The fragrant wind from the twenty-four bridges cannot reach her” as suggesting that the woman in the painting is untainted by the sensual associations of the courtesan quarters. In line 4, “Yellow scrolls” 黃卷 (huang juan) can mean Daoist texts, but it can simply mean books. The phrase we have translated “springtime of her youth” is 三春 san chun, which literally means three springs. It could also mean the third month of spring. The word we have translated green in line 5 is 碧 bi, which is the green color of jade, suggesting that these willows are luminous, in contrast to the willows in the second line, which are dark, and possibly even somewhat obscured. In line 9 we have translated 柳絲 liu si as willow floss. 絲 means silk but it also means threads. Paul Rouzer suggests in his analysis of Lin Daiyu’s flower poem (where he translates 柳絲 as willow floss) that the threads invoke a bond that might exist between a woman and her lover. He also points out that 絲 is a homophone for 思 which can mean longing. Thus one might read “willow floss” as having erotic connotations. Spring wind certainly has erotic connotations.

Widmer also glosses “enshrouded in wind and dew” as suggesting difficult circumstances.

In the fifth stanza, the phrase “flower by the wayside” may suggest a beautiful woman, perhaps a courtesan, who has been discarded by a lover.

The phrase translated “Daoist Scrolls” is 黃卷 huang juan, whose literal meaning is yellow scrolls. The phrase does in fact mean Daoist scrolls; but the translation necessarily obscures the color. In the very next line we read of the red of the flowers, the green of the willows. The yellow of the text adds to the vividness of the color, and perhaps suggests a connection between text and nature–they are both a part of a world of color.

The scene being described–the peaches, the willows, the balustrade—is not the scene in the painting, but rather a scene in the poet’s imagination. Or, to be more precise, it is scene which the poet is inserting in the courtesan’s imagination.

Notes on painting: This painting is sometimes called “Lady at her Dressing Table.” If you look closely at the painting (and to see this you may need to go to website of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and zoom in on the painting, you will see that shoes are peeking out from under the gowns of both the woman at the dressing table and the woman making the bed. This clearly indicates that the women are courtesans–no Qing dynasty painter would have portrayed a lady’s bound feet. The rumpled bedclothes are clearly an indication that sexual activity has recently taken place.

COLOPHON

Now that we’ve read the colophon, let’s take a look at the way it functions on the painting.

The top image shows the Wang Qiao painting with the colophon digitally removed from the upper left-hand corner. The bottom image shows the painting with the colophon intact.

Colophon is the term used to describe a text, often but not always a poem, written on a painting. Sometimes a colophon is written by the painter, but more often it is written by someone else–sometimes a friend or a patron, but also often by a later collector.

The writing of colophons on paintings suggests that the painting and the viewer exist in a dynamic relationship. A colophon permanently alters the painting and changes the spatial relationships in the painting. The painter thus does not have the last word on the construction of the painting.

Let’s take a closer look at the images. The colophon in the painting is a square block, which balances both the block of the bed and the block of the dressing table. It seems like it is an integral part of the composition of the painting.

The other image was digitally reconstructed by Jay Kim using the Erase function in Photoshop so that we may see what it looked like before Zhou Qi 周綺 set her brush to write the colophon. Especially after our eyes have become accustomed to seeing the painting with the colophon, the painting without the colophon looks almost bare. Is it our imagination, or does the blank space in the right of the painting seem as if it is inviting someone to write a colophon?

The last two characters in the colophon are chu gao (初稿) which literally means rough draft. The words cannot have that meaning here–one does not use an ancient painting to practice calligraphy. Rather, the phrase is probably a self-deprecatory phrase, suggesting Zhou Qi’s 周綺modesty to the viewer of the painting and the reader of the colophon.

Suggestions for further reading: Ellen Widmer, Beauty and the Book.