Sleeveband Embroidered with Scenes from Dream of Red Chamber

And now we move from a spectacular work of high art, an embroidery that was truly “painted with a needle” to something much more ordinary, something much more intimate–embroidered clothing. In Qing China, the clothing of both men and women was often elaborately patterned. Sometimes the patterning was done in the weave, with brocade, or with a technique known as kesi, which resembles a delicate tapestry. But during the Qing, the patterns on clothing were increasingly made by embroidery. Sometime the embroidered clothing was produced at home (by family members or servants); sometimes it was made by seamstresses or tailors. Embroidery was considered an appropriate activity for women of the upper classes. In the Dream of the Red Chamber, we frequently see the young women of the garden, both members of the Jia family and their servants, embroidering, and we occasionally see reference to embroidery patterns. Family members are proud of the fact that embroidery done within the confines of their household was superior to anything available on the market. However, reference is made in the novel to payments made to embroiderers, suggesting that the volume of work exceeded the capacity of the household to perform it.

And now we move from a spectacular work of high art, an embroidery that was truly “painted with a needle” to something much more ordinary, something much more intimate–embroidered clothing. In Qing China, the clothing of both men and women was often elaborately patterned. Sometimes the patterning was done in the weave, with brocade, or with a technique known as kesi, which resembles a delicate tapestry. But during the Qing, the patterns on clothing were increasingly made by embroidery. Sometime the embroidered clothing was produced at home (by family members or servants); sometimes it was made by seamstresses or tailors. Embroidery was considered an appropriate activity for women of the upper classes. In the Dream of the Red Chamber, we frequently see the young women of the garden, both members of the Jia family and their servants, embroidering, and we occasionally see reference to embroidery patterns. Family members are proud of the fact that embroidery done within the confines of their household was superior to anything available on the market. However, reference is made in the novel to payments made to embroiderers, suggesting that the volume of work exceeded the capacity of the household to perform it.

Research by Rachel Silberstein and other scholars has demonstrated that by the nineteenth century, collars and sleeve bands were readily available on the market, and could be added to home-made clothing. Thus clothing could be produced as a hybid between the homemade and the commercial, even if families such as the Jias looked down on such commercial products.

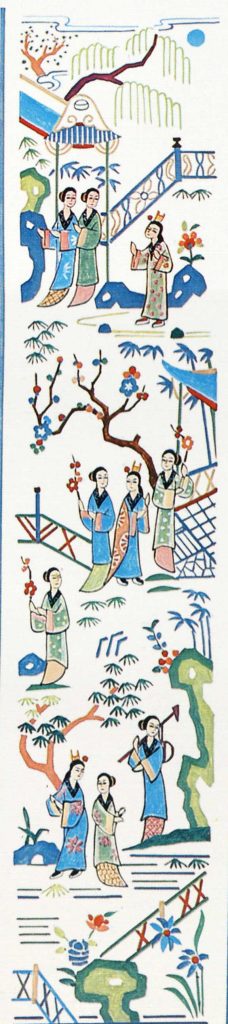

The image to the left shows a commerically available sleeve band. Such bands were readily available on the market and could be added to home-made clothing.

Embroidered sleeve bands might contain scenes from well-loved novels or operas. This image is a sleeve band containing scenes from the Dream of the Red Chamber. Note that Baoyu is wearing his characteristic headdress, with the red ornament on top. The bottom scene in the sleeve band is of Daiyu burying flowers. She is carrying a hoe on her shoulder. Do you recognize the other two scenes?

The detail on the right (taken from the top frame of the sleeve band) shows Baoyu in his characteristic headdress, with the red ornament. Note that Baoyu appears in all three frames.

The detail on the right (taken from the top frame of the sleeve band) shows Baoyu in his characteristic headdress, with the red ornament. Note that Baoyu appears in all three frames.

The Asian Art Museum in San Francisco holds an example of a piece of cloth with sleeve bands and collars.

For more on embroidered sleeve bands, see Rachel Silberstein, “Cloud Collars and Sleeve Bands,” as well as her A Fashionable Century.

YANG ERYOU 楊二酉 ON EMBROIDERY

In the eighteenth century, Yang Eryou, who received the highest civil service degree in 1733, wrote about embroidery in a way which both trivialized and celebrated it:

Embroidery is but a trivial skill. Those gentry women started to learn it from childhood and applied it to clothing, and some people take embroidery as nothing but fancy decoration. In recent times there appeared the Gu family in Sujun [Suzhou; sic.] who started to make embroidery paintings. Whether their subject matters are human figures or birds or flowers or insects or fish, all have subtle shading of colors, and they are able to conceal the traces of the needle and threads to the extent that one cannot tell whether it is a work of embroidery or a painting. When embroidery reaches such a [high] level, what more can be added? …

自 蘇氏若蘭手製迴文,而女紅之能事畢矣。… 如若蘭者, 創造規模,經營布置,不爽絲髮,其靈心夙慧, 爲何如 也。是知天地清淑之氣鍾於女子,亦可以奪造化之工,而 窮奇極妙為不可及。刺繡一道,小技也。閨秀輩童而習 之,著之衣袂,有以爲絢綵飾觀已耳。近世有蘇郡顧氏 出,始作畫幅。凡人物翎毛花木蟲魚之類,淺深濃淡無不 如意,並無針痕縷迹,使人不辨為繡為畫也。繡至此,蔑 以加矣。… 雖俱折枝小景,而枝葉翻正、花蕊向背,真得 寫生三昧,又無煙火氣,信非顧氏不能。益徵天生奇才, 曠代一遇,即小技尚可以名世。況夫絲綸在手,經緯天 地,可以製美錦而補華袞者。天豈令鬱鬱久居此乎?50

楊二酉1780?, jinshi 1733) Cited in by Huang I-fen, p.95