Chapter 2: Ways of Understanding Families and Technology

2.1 Ways of Understanding Families and Technology

Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less.

― Marie Curie

Chapter Insights

- “Family” can be defined in various ways; there are generally accepted roles and functions families fulfill for their members and to society.

- As the family operates as a system, there are characteristics, processes, and influences on its functioning.

- Extant theories of the family — including family development, symbolic interaction, feminist and social construction — are useful in understanding dynamics of technology use and family access.

- While theories of media use help us understand how people vary in their use in relationships, they might be insufficient to apply to family research without some adaptation.

- This chapter presents Lanigan’s Family Sociotechnological Framework, along with Hertlein and Blumer’s Couple and Family Technology and Life Course. Consider how these frameworks characterize the role of technology in family dynamics and functioning.

- With evolving research and theory, our consideration of families’ integration of technology and its impact on family life might drive new ways of understanding families altogether.

- After reading this chapter, identify what you feel inspired by, the questions that remain for you, and the steps you can take for your own technology use to be more intentional.

As family scholars, when we address questions of the impacts of technology use on family life, we begin with the foundation of how the family is understood, its processes, the dynamics of relationships between family members, and how the family is situated within the wider social ecology. On this foundation we can more clearly see ICT is used by families for communication and family life management. ICT enables a variety of processes between individuals in the family, and on behalf of the family, helping achieve the functions of the family. This chapter reviews key family theories and perspectives, and presents newer theories specific to technology use. The chapter ends with a discussion of two relevant models that blend traditional family constructs with the reality and potential of family internet, device, and application use.

|

|

|

Consider these questions about your own family:

- How do you define “family”? What influences how you view and define “family?” What is a “happy family?

- What are the functions or purposes of a/your “family”? Who are its members? What roles do they play?

- Is your family “successful” as a family? Effective? Healthy/functioning?

- What influences your family’s well-being — positively and negatively, internally and externally?

- How has your family changed over time?

Defining Family

The definition of family depends on the perspective of the person doing the defining. Some consider a family to consist of members who are legally and biologically related. Governments define the construct of a family when distributing goods or services, or when allocating rights and privileges. The U.S. Census Bureau, for example, defines family as “a group of two people or more (one of whom is the householder) related by birth, marriage, or adoption and residing together; all such people (including related subfamily members) are considered as members of one family.” [NOTE: “householder” by virtue of a name being on a title or lease agreement]. This definition is broader than the same agency’s definition of a family group and family household, which can include nonbiological others and ascribes leadership. Family is sometimes defined by its structure and membership. While some may restrict this to a traditional notion of “immediate family members,” including the parent or parents and children, others consider anyone living with and related to the immediate family., including grandparents and other extended family members. And for others, “family” is a concept borne of connectedness, similarity, and shared values: two or more people who are committed to each other and share intimacy, resources, decision-making responsibilities, and values.“family” is a concept borne of connectedness, similarity, and shared values: two or more people who are committed to each other and share intimacy, resources, decision-making responsibilities, and values.

For the purposes of our discussion of technology use, if we are to have a generalized sense of technology’s influence, it is important that definitions of families are shared across research when comparing studies.

With an understanding of what a family might look like, let’s consider its function. This can seem like an odd question when we all were born into families and are part of families, even if they’ve changed in composition or meaning over the years. The family is such an expected, natural unit of society that to question its function can seem jarring, yet the question allows us to better understand the processes and structures that help the family to be successful — processes and structures that are facilitated or affected by ICT.

Families serve functions to themselves as a cohesive unit, to their members, and to society (including culture). For example, the definition above indicates process words: “commitment,” “sharing” — yet to what end? Perhaps the function that nearly everyone can relate to is the family as providing emotional support, and caring for the physical, mental, social, and (for some) spiritual well-being of its members. Families also perform generative functions for society. In fact, birthing into a family unit and socialization of children is a role most cultures confer on families. In so doing, families provide a value system of beliefs that are passed through generations, maintaining members’ emotional, social, physical, and spiritual well-being.

Readers are encouraged to explore the rich cultural and ethnic dynamics through which families are guided in their norms, traditions, roles, and expectations (e.g., Gardiner, 2017). It is through these caregiving functions and the passing along of traditions that family well-being becomes of interest as an economic value.

As noted by the World Youth Alliance:

The family facilitates the transfer of culture from the older generation to the younger generation, passing on values and the importance of hard work, discipline, and solidarity. The strong examples set by parents, grandparents, and extended family members foster the work ethic and moral character of individuals entering into the workforce, which positively impacts the quality of the workforce and reduces youth unemployment. Thus the important role of healthy family structures in the economic growth of society must be recognized and promoted.

This section reviews several conceptual frameworks common to family science. Those selected neither exhaust the list of family theories, nor are they “best.” They represent some classic family theoretical perspectives that align well to a shared understanding of technology’s application to family structures, processes, and outcomes. Beyond these, readers are encouraged to explore other theories such as feminist theory, valuable in viewing the lens through which society presents images and communication about women’s roles, the subordination of women’s roles, and gender equality and independence. Feminist theory might explore messaging through ICT, and global gender division in household property (including the possession and use of technology) and employment. Social exchange theory, when applied to the family, examines the goal orientation of individuals. It assumes that the individual acts in ways that satisfy goals, and that rational choices in pursuit of that goal consider the benefits and consequences, and size up available resources. With regard to the family, social exchange theory might be used to examine the influence of a family member in creating a crowdsourced fundraiser online, and the balance of perceived potential rewards and constraints (see related research by Kim et al., 2018).

Suggestions on further reading on family theory are offered in the Additional Readings and Resources for this chapter.

Family Systems and Ecological Influences on the Family

Viewing families as open systems, and families as part of a wider social ecology, are key principles in our basic understanding of family life. A Family Systems perspective builds from classic Systems Theory, which views the organism as an ongoing system of interconnected members. In an open system, members influence each other, and each member is influenced by external factors. The family systems perspective focuses on the family as an ongoing system of interconnected members. Extensions of family systems theory include Bowen’s theory of the family and systemic change over generations of interactions and emotional development.

In the systems perspective, the whole is viewed as greater than the collective of individual parts. The family as a distinct unit has its own characteristics, structure, strengths, and weaknesses. The system is dynamic and transactional, sharing information (in the family via communication), and through that sharing affecting the other members, as family subsystems (e.g., a parent and child) or the family as a whole.

Olson’s Circumplex Model (2003) features family operations through processes of communication, cohesion, and adaptability or flexibility. Communication takes many forms — verbal, nonverbal, symbolic, literal (e.g., text, written or spoken language), and figurative. And as with any communication from sender to receiver, articulation and interpretation may vary. Families also demonstrate aspects of cohesion. The cohesion of a system reflects its strength and degree of connectedness as a whole, and across its individual links (e.g., a parent-child subsystem). Connectedness reflects a balance of separateness (or autonomy of its members for growth) and togetherness for comfort, safety, and stimulation for growth. It is excessive neither in member separateness (indicating disengagement) nor member togetherness (reflecting enmeshment). Instead, it values demonstrations of commitment and closeness while respecting member individuality. Cohesion also reflects the strength and resilience of the family, particularly in the face of stress. As an example of technology research framed from a systems perspective, Ferguson and colleagues (2016) examined the influence of employee mobile technology use during time with the family. Enhanced mobile use contributed to work-family conflict and reduced work attention. For the spouse, increased mobile use by the employee (family member) contributed to spousal conflict and decreased commitment to the employee’s organization.

As an open system, the family is able to take in new experiences, grow, and change. A closed system avoids change and maintains the status quo. All families and individuals in families face conflict, so another hallmark of healthy family functioning is flexibility — the ability to work through change and conflict and remain stable, albeit transformed. The strength of the unit is in how well it withstands, processes, and recovers from the stress or conflict. For example, if a family member comes out as gay, an open family system adopts a new understanding of that member on their terms and identity and adjusts. A closed family system rejects a non-traditional (to them) idea of the family member’s sexual orientation. This rigidity is experienced through a lack of change in acceptance, a lack of communication, and a lack of openness to re-identify as a family.

Technology is another example of the need for system flexibility. A family system that is open embraces and understands the role that ICT plays and adopts it in ways that benefit yet don’t diminish the family’s functioning. A closed system stays resistant to using ICT; seeing it as not beneficial, and thus risking the lack of growth or efficiency. In the 2018 podcast interview referred to in the last chapter, Kevin Kelly speaks of the Amish, who selectively choose whether to embrace smartphones. They don’t reject innovation out of hand, but rather ask some community members to experience the innovation for a year to determine if it benefits the whole community.

Flexibility can be also viewed as the necessary, day-to-day adjustments made when dealing with external influences small and large. Whether the conflict comes from a parent and child negotiating how much time the teen spends on their phone, or a family recovering from their home being hit by a hurricane, families need to possess the characteristic of flexibility. Flexibility may be seen in compassion, understanding, and communication between members. It may require shifts in structures and responsibilities, in the allocation of resources, and in the focus of time and attention.

As an open system, the family and its members are influenced by their ecology, or surroundings. Contexts can include systems that families are a part of — social systems, belief systems, and extended family systems. Social systems are the neighborhoods, workplaces, schools, and people that families and family members connect with on an ongoing basis. Belief systems relate to the family’s norms, values, traditions, and possibly religious or spiritual elements that guide practice and goals. Extended family can also convey and reinforce culture and traditional norms and values, and can offer resources in the form of emotional, informational, and practical support — support that can be positive, yet can also have a negative impact (e.g., stress).

Readers may want to dive into systems perspectives specific to family stress and coping (Hill, 1958; McCubbin & Patterson, 1982), family resilience, and family strengths (DeFrain & Assay, 2007; Patterson, 2004). While different, these models each reveal characteristics that help families through conflict and crisis. Hill’s (1958) ABC-X model of family stress and coping, for instance, conceptualizes the family encountering the antecedents (A) of stress, responding based on their perception of resources (B), and experiencing the consequences (C). “X refers to the endogenous variable (X) of the ABC-X model as the degree to which the stressor precipitates a crisis to the extent that a family can no longer remain functioning” (Rossino, 2016, p. 1). The double ABC-X model refers to the family’s post-crisis response and adaptation or dysfunction. Individual family differences dictate the perception, response to the stressor, and response to the consequences. As Patterson (2004) notes, family resilience can be viewed as an outcome and measure of family adjustment to stress. It can also be assessed as a process in terms of the meaning families ascribe to stress and the actions with which they respond. Family strengths reflect positive abilities and attitudes toward life and each other.

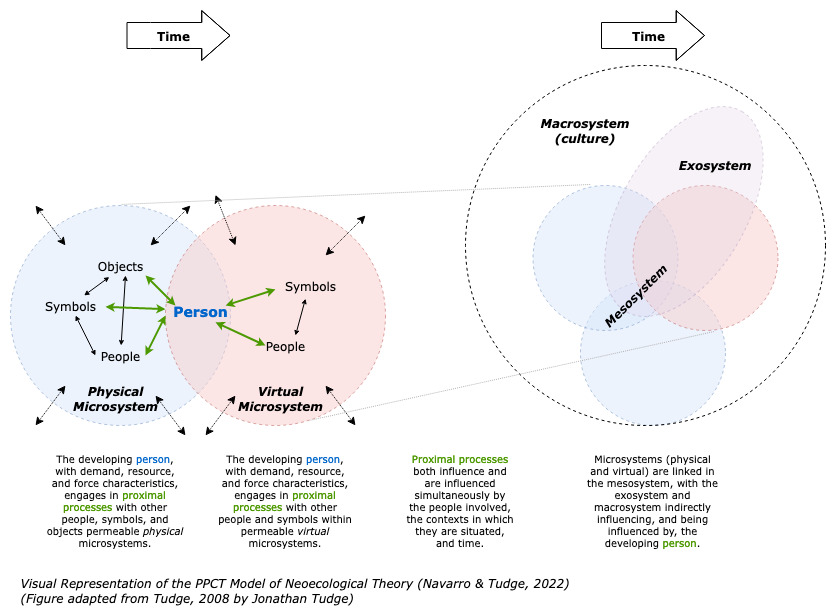

Families are also greatly influenced by the wider systems they are part of. As they are changed by that influence, they influence others within the family through their interactions. As the family is changed, its internal workings return it to a steady state, or homeostasis (much like the human body when subjected to abnormal conditions that produce stress, like running fast or metabolizing a high amount of sodium). Returning to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological perspective introduced in the previous chapter, we are reminded of the individual as influenced by proximal (nearby, frequently interacting) influences and those more distal, infrequent, and remote. Human development is influenced by the unique composition of the individual through interaction with people, in contexts, through processes over time. The family is a proximal influence on individual development, carrying the unique composition and characteristics of its members, history, and culture, and is influenced by the proximal and distal systems within which it interacts.

That unit can experience the same contextual influences as others, yet respond differently. These influences can include physical settings, time, events, political conditions, climate, and resources made available by location. Settings can influence the resources available to families, and threats to family well-being.

Take, for instance, a family living in a suburb of a major metropolitan city and another living in a remote rural town. On one hand, all families living in a particular place are exposed to the same availability of resources. This is where jurisdiction matters. On the other hand, within that setting, family use of available resources will vary. Navarro and Tudge’s (2022) “technologization” of Bronfenbrenner’s framework identifies the virtual environment as a setting complementary to yet separate from the physical world. The virtual environment offers a location for interaction and exposes the individual to resources. The authors adapt the notion of cultural influences in more distal settings, reflecting the virtual environment. As discussed in more detail in Chapter 5, which focuses on technology influences on human development, they observe that “the rapid adoption of digital technology likely differentially impacts the development of [individuals] depending upon the values and beliefs, resources, and social structure of their society.” (Navarro & Tudge, 2022, p. 8). Events are another influence on the family as a system. As we’ve experienced with the COVID-19 pandemic, events can create worldwide impacts that have ramifications long after. The family is negatively impacted when subjected to influences of poverty, discrimination, and racism, which can reduce access to resources.

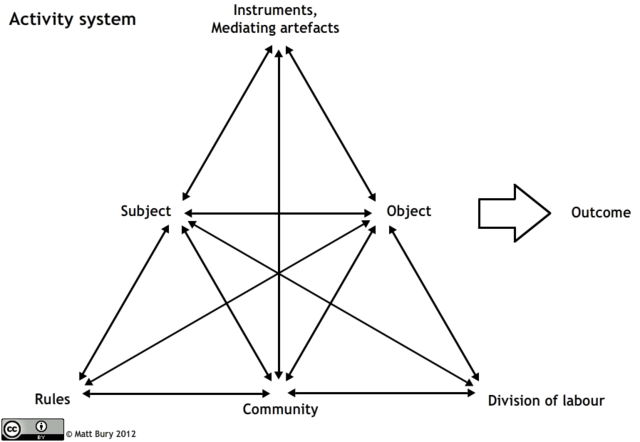

A perspective related to systems theory is activity theory, which articulates how social action is mediated through social objects and social organization, affecting thinking and behavior. Activity theory stems from the work of social cognition theorists like Vygotsky, helping explain the individual’s mental capabilities resulting from interaction with the community, culture, and technology surrounding it. The theory’s application to information and communications technology is apparent, yet it also considers others with whom the individual interacts within the system. Activity theory addresses the objective of the system, internalization of the actors, tools used by the actors, division of labor, rules, and conventions. One example of activity theory as applied to technology and human interaction systems examines the use of online communities for professional development (Baran & Cagiltay, 2010).

Additional Perspectives on the Family

Family Development

Among the major natural and inevitable influences on the family are the individual development of its members, and the development of the family as a whole (Carter & McGoldrick, 1988). The family system is intended to foster the development of its members. There is certain predictability with the continual development and change of individuals in the family (e.g., children developing physically, cognitively, socially, and emotionally from birth through adolescence), though this still requires flexibility by the family. When the development of a member is impeded, that sense of predictability and order is thrown off.

As we consider development of the family and within the family, think about how family members deal with various roles and developmental tasks as they move through life stages: the initiation of couple relationships, commitment, and formation of the family; transitions to parenting; raising young, tween, and teenaged children; launching those children; and mid-life, retirement, and possible caregiving for elders. Within the family, one member’s efficiency in completing the tasks of development directly impacts the development and activity of other family members. For example, a ten-year-old who is emotionally and cognitively mature may be given responsibility for caregiving to their younger siblings, making it easier for the parents to spend more time at work earning money that provides for the family as a whole. Viewing family development as a response to the developmental trajectory of its members encourages attention to the family process, acknowledges the family as a dynamic system, and focuses on individual and contextual change over time.

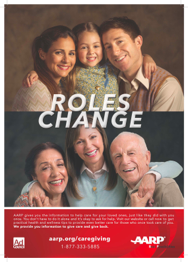

This graphic from the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) nicely demonstrates the developmental shifts that happen to whole families over time. As it shows, roles change over time. The full family unit of parents and child conveys the responsibilities of parenting and child-rearing. Thirty years later, the full family unit conveys the shift to older parents requiring some level of care by the adult child, even if that means emotional support rather than practical or financial assistance.

Given the multiple influences on individuals within the family, and the stages in which the family itself shifts, viewing change in a family acknowledges influences such as gender expression at each life stage; the health, addictions, and ability status of family members; immigration; and characteristics of race, ethnicity, and culture as carried out by the family, and as society reacts to those identities within the family.

Symbolic Interaction

Symbols offer shared meanings that are expressed through verbal and nonverbal communication. The Symbolic Interaction framework helps explain how we learn about and through roles by communicating with each other about various roles in our society. In families, repeated patterns and behaviors express roles and meaning to members and to wider social systems. While a role in a family includes expected behavior in a given social category (Olson et al., 2014), role making includes interacting with others in ways that help teach the role or change its expression. Women’s caretaking, for example, may be learned from watching women in the family and extended family; these caretaking roles are reinforced by others in the family and wider society.

Emotional bonds are created from activities conveyed by one’s role. Roles also symbolize the importance and power of a family member in fulfilling functions. The power results from an implicit negotiation between individuals in the family. Within an individual family, a woman’s extreme caregiving may convey her power in that family (e.g., the matriarch).

Consider how roles may play out in family member technology use. A son whose role is in sibling oversight and monitoring, for example, may be given a mobile phone early to help him communicate with other family members.

Feminist Family Theory

Within the perspective of internal family roles in which members carry out functions that fulfill internal and external family goals, feminist theory challenges the patriarchal paradigm that proscribes certain roles to women (Allen, 2016). Traditionally women are viewed as caregivers, holding roles through marriage that serve the husband, bear children, provide the dominant role in parenting, complete domestic (household) management, and oversee care for elders. In the feminist framework, roles are equal and women maintain responsibility for financial matters and as decision makers for the family, including holding down employment. This doesn’t mean taking on traditionally female and financial roles, but equal division of labor. Because this perspective challenges the traditional model, it also accepts a degree of conflict in households as a natural course of role negotiation. In this book, discussion of access to technology greatly concern views of women in global societies. There is significant misalignment in access to mobile devices and to the internet by gender, particularly in less developed countries in which fewer people hold access. For example, although in North America where 95% of the population has internet access, there is a 1% difference between men (95%) and women (94%), in South Asia, the difference is much wider with 37% men and 18% women. Feminist theory questions these access rate differentials.

Patterns of Family Communication

As discussed, family communication is a process by which family outcomes of connectedness and cohesion occur. Interactions, and transactive communication, and the conveying of information through verbal and nonverbal actions — these are part of families’ daily lives. Families also communicate care and affection through rituals and traditions. These may be unique to a given family (e.g., birthday, graduation) or may be a family celebration of a wider cultural tradition. Given the uniqueness of the family in society, and the uniqueness of each family, it makes sense that families vary based on their patterns of communication.

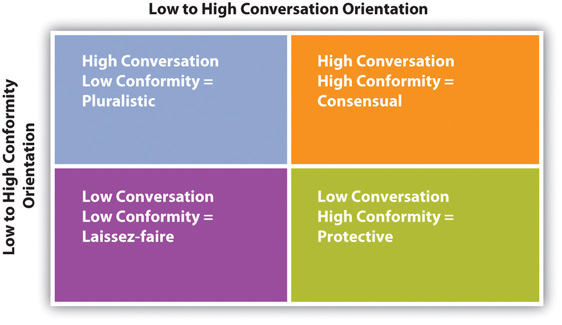

A social cognitive perspective on family communication is Keorner and Fitzpatrick’s (2002) identification of patterns, which adapts relational cognition and interpersonal behavior. Their model of patterns identifies two dimensions that represent the family’s shared reality: conversation and conformity. Conversation is communication about topics; conformity is expression of values, behaviors, norms, and beliefs. Families exhibiting low communication interact infrequently, and topics may be limited. Those who are low in conformity represent diverse perspectives and interdependence in interests. Information and influence from external sources are welcome in families who experience low conformity.

Koerner and Fitzpatrick’s work describes climates created by families based on the two dimensions. Those high in conformity yet low in conversation may be protective; when both conformity and conversation are low, the family is laissez-faire. Those high in conversation and low in conformity experience a pluralistic climate, and when both conversation and conformity are high, family patterns are said to be consensual.

Social Construction

Social construction is the development of a belief, construct, or concept based on repeated interaction with the society around an idea. This interaction reinforces certain beliefs and understandings, developing identities over time and through life experiences. Consider how the family might be a social construction — a building up of certain beliefs about something — and the forces that influence those beliefs. Day-to-day interactions with others in our neighborhoods, workplaces, and schools convey information about families.

At a wider level is how the family is represented in the media, in books and literature and stories, and now as passed along by the internet and by social media.

Let’s consider how the family has been presented in various television shows over time. Each link below describes a television show popular in its decade:

- In the 1960s (Father Knows Best)

- 1970s (The Brady Bunch)

- 1980s (The Cosby Show)

- 1990s (Full House)

- 2000s (Modern Family)

- 2010s (One Day at a Time (reimagining the series with a Latino family)

In each of these depictions, the family reflects a dominant belief system at the time — in the 1950s, the view of the family as patriarchal, white, and middle class; in the 1970s, the family as blended and heterosexual; in the 1980s, the Black upper-middle-class family of the Cosbys; in the 2000s, family systems made richly diverse (in some ways) through inclusion of age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, marriage, remarriage, and gay marriage. Certainly, real-life families vary greatly from these depictions, yet media representations convey the ways in which the larger society defines a family. Our critical lens must explore the voices and faces and experiences missing in these shared constructions. Often, the perspectives of women, immigrants, non-traditional families, families with members who have disabilities, and those with non-dominant gender orientation or cultural and religious traditions are silenced, marginalized, or — possibly worse — presented in a stereotyped way.

Social construction as it relates to technology can be viewed as a response to technological determinism. Mauthner and Kazimierczak (2018) observe that technological determinism would argue that the changes brought about by technology create material constraints to human agency, and determine history and culture. They cite Heilbroner’s (1994) view of the acquisitive mindset, or behavior of maximizing as the mechanism that facilitates technology’s change and impact on history. Mauthner and Kazimierczak observe that technology is independent in driving social change, “but rather from the broader sociopolitical contexts in which they are designed, developed and adopted” (p.23) And so, the individual or community has less agency in the changes brought about by technology. The authors cite Sismondo’s (2010) illustration of the watch as an example of SCOT (the social construction of technology). The watch is crafted to be functional in its ability to tell time, to have esthetic value, to be profitable, to make a statement about the person who wears it, and other perspectives. Even the action of telling time can be perceived as fulfilling different functions – measuring a length of time, maintaining time, acting as a stop watch. In short, the perspective of the watch is socially constructed by those using it. In social constructivist notions of the family, the family is understood within the particular social contexts that define their nature and effects, technology too can be understood within social negotiations and logic. Mauthner and Kazimierczak provide an example of research that integrates social constructivism to technology use and family work balance through Wajcman’s work on gender (p. 23). As will be discussed in chapter 9, technology integration in the balance of boundaries and role demands across work and family spheres is less determined by the mobile capabilities of devices and use of the internet, but through constructed action by users and the social contexts in which they operate.

Social Networks of Families

Social network theory stems from the sociological study of human relationships and the flow of capital across social ties. Social networks are created by relationships, not defined by the boundaries and contents of an established institution. They are characterized by dyadic links and network dimensions (e.g., size, shape, density of interconnectedness), by relational transmissions across connections, and by time and space. They have power through their social and societal influence on individual behavior and the collective behavior of the group. Network structures determine the content, quality, and flow of influence within the network (bridging, bonding, latent social capital, social support). Influence can occur on a small scale (e.g., from person to person, from small group to individual); it can also happen across many interconnected network connections, creating an aggregate influence more potent than the individual connections within whole networks.

The perspective of Moncrieff Cochran (Cochran, 1990a, 1990b; Cochran & Niego, 2002; Cochran & Walker, 2005) on the social networks of parenting applies network theory to one role in the family, yet its principles make it relevant to other dimensions of family roles and influences through relationships. It suggests ways that the larger ecological, structural, and relational dynamics of a family member’s life (in this case the parent) may impact child well-being, working through the parent or operating directly on the child. Echoing the tenets of social network theory, Cochran and Brassard (1978) observed that it is through the structure of those connections and relational processes that networks have the capacity to convey information and models of behavior from the larger society through the parent, and thus to impact parenting behavior.

Network membership is greatly constrained, even imposed by one’s position in society by virtue of such factors as culturalvalues and beliefs, income and education, and geographic location. Christakis and Fowler call this “situational inequality”(2009, p. 31). The other significant influence on network realities is the range of factors that motivate an individual’s recruitment, selection, and engagement of network members. Identifying the forces that influence network formation and engagement illuminates avenues that public policy and programs can follow to affect network membership and involvement.

The social processes conveyed through network interaction — either directly involving the parent, or happening indirectly, as with hyperdyadic spread or broader network effects — contribute to observed parenting behavior. In general, social support through offers of practical assistance, information, and emotional or psychological aid has been studied as a process through which network influences parenting. Buffering, modeling, teaching, direct assistance, and providing opportunities for interaction are dimensions believed to affect parental behavior.

Internet and social media applications of Cochran’s network perspective

Cochran’s model is a useful conceptual guide for research on parents’ social networks and on outcomes of parenting resulting from online and offline experiences. The framework challenges researchers to regard process and structure as keys to social relationship dynamics and meaning. The use of social network sites might provide parents with bridging social capital (that exposes them to diverse child-rearing perspectives, including a blend of lay advice and professional views), and with bonding social capital to maintain close ties, even with those intimate, trusted, and depended on for social support yet infrequently seen. Family researchers may look to network perspectives to consider other dimensions of outcomes that may be the product of social network dynamics and that may have an influence on the child, including parent development and the parent-child relationship. As a mechanism for information, communication, self-expression, and collaboration, the internet holds possibilities to influence the individual development of the parent (e.g., identity validation). And explorations of impacts on the parent can examine how online interactions might have offline benefits either to parents directly, or indirectly to their children.

Before moving ahead, consider some questions that apply technology to the family theories discussed in this section:

- How might the use of cell phones or smartphones figure into family system functioning?

- What might the introduction of smartphones to the family mean to family functioning regarding family member roles?

- How might “rules” related to technology play a part in the enactment of the roles?

- How does the sense of family member development relative to technology use, attitudes, or comfort figure into the family functioning for cohesion? Communication?

- To maintain the family functioning, how might family members need to demonstrate flexibility in technology use or attitudes?

- How is the family conveyed through social media in ways that point to it as a social construction?

Theoretical Perspectives on Media and Communication

Are family theories sufficient to answer our questions about technology use by families? What limits to exploring technology’s impacts might be found in these traditional theories of family life? As will be discussed in the next section, specific perspectives on ICT present ways of understanding innovation in human life that are not adequately addressed in existing theories. While communications theories represent a field of study beyond the scope of this book, selected theories will be briefly introduced here as indicative of perspectives offered on ICT aspects and use, and on the impact of computer-mediated communication (CMC) on human behavior and collective society. Additional authors, such as Dworkin et al. (2018), have discussed these theories relative to their insight on families.

Media Richness Theory

Media richness theory proposes that media use or selection depends on the ability desired to convey messages, particularly those of an emotional or relational nature. As the figure below conveys, richness deepens with formats that approximate the experience of being face-to-face or physical presence. In Simpson’s (2013) research on media richness, media selection is determined by considerations of tool or format experience, perception of tool capabilities, and social circumstances.

Media Multiplexity

Haythornthwaite’s (2005) media multiplexity theory conveys the meaning of intimate relationships through the use of devices by number and variation. According to the theory, relationships are stronger when conveyed through the use of multiple devices and connections. Being friends with your sister on TikTok, texting her, IM-ing her through her Instagram account, and using FaceTime for weekly chats demonstrate the platforms used to maintain your relationship. Balayar and Langlais’ research nicely represents media multiplexity in family relationships. They add the dimension of family perspective — individualistic or collectivistic — as this is an essential factor determining expectations for closeness. From a survey of college students, the authors revealed that those from collectivistic cultures appreciated face-to-face contact with parents, as it correlated with closeness and love. This did not hold for other family member relationships.

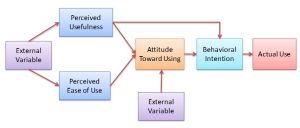

Technology Acceptance Model

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) proposes that perceptions of technology as both useful and easy to use have a direct and positive influence on technology attitudes, intention to use technology, and eventual use. (see Figure below)

The TAM is derived from Ajzen’s theory of reasoned action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) which proposes that attitude toward a behavior is determined by the beliefs about the consequences of the behavior and by an individual’s effective evaluation of the consequences. Among Family and Consumer Science teacher candidates (Ma & Pendergast, 2008), perceived ease of use was the most significant influence on intention to use technology. Limitations of the TAM, as Davis (1989) describes, are the inclusion but lack of specificity about external variables that influence attitudes directly, and the influence of external variables as mediated by attitude components, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness.

A Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT, Venkatesh et al., 2003) identifies attitudinal and contextual constructs that motivate use, including the perception of success (e.g., the technology is useful to the purpose), effort (e.g., the technology is easy to use), influence from the social context (e.g., encouragement of others), and facilitating conditions (e.g., the availability of training). Personal factors that may condition use include age and previous experience with technology.

The author’s repeated study with parenting and family education professionals employs Teo et al.’s (2008) model of context variables that influence the TAM (e.g., Walker, et al, 2021), discussed later in Chapter 11: subjective norms and facilitating conditions. Translated to the workplace, external TAM constructs are “workplace expectations” and “workplace infrastructure” — technology use by family professionals would be influenced by their acceptance attitudes about technology, whether those attitudes were shaped by workplace conditions of being encouraged to use technology, and being given the resources that help technology be easy to use and seen as useful. Ertmer’s (1999) perspective on technology use also supports extrinsic factors such as training, access to devices, and organizational climate, yet sees them operate as “first order” influences, and views attitudes as second-order influences on use.

Frameworks on Families and Technology

Early in the millennium, advances in ICT use by families had family scholars calling for theoretical models that could shape evolving research and help depict and perhaps predict how new media impacted individuals within families and families as a dynamic, changing unit (Aponte, 2009; Blinn-Pike, 2009; Watt & White, 2000). Research using family theory as a basis for the study of technology integration certainly helps (e.g., Sharaievska & Stokolska, 2015). Recently, a variety of models have been proposed that integrate family dynamics with technological affordances and societal change (Dworkin et al., 2019; Mauthner, & Kazimierczak, 2018). This chapter focuses on two models that characterize family processes within traditional frameworks and that highlight aspects of the technologies themselves that inform selection, use, and impact.

Both models come from family systems and ecological perspectives; they regard ICT as tools external to the family unit that facilitate family processes (e.g., communication, knowledge acquisition) and structures that play out continuously in virtual and “real” worlds. The use of ICT by families is a recursive process in that changes in the technologies themselves can occur (witnessed by the growth in the availability of social and mobile media in response to popular use), resulting in differences in use due to the affordances provided. The recursive nature of ICT use is also seen in changes to family systems and processes as a result of the family interacting with and because of technology.

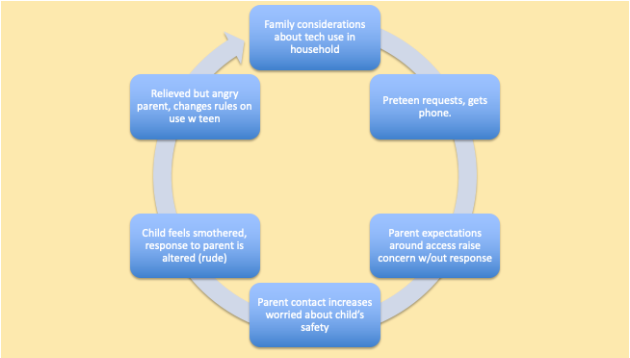

The figure below depicts changes in rules as a family experiences a member’s technology use. The daughter wants a phone and is offered one with an implicit understanding that she will text her parents when she is away. When this doesn’t happen, the discussion that ensues between the daughter and the parents results in a negotiation and a change in the rules to maintain family connectivity and balance.

Both models also reflect variation in use by individual or family factors and technology characteristics. Lanigan’s (2009) socio-technological model offers a comprehensive view of technology use and family life impacts; Hertlein’s (2012, 2018) is more specific to potential impacts on the structure and processes of couple and family relationships.

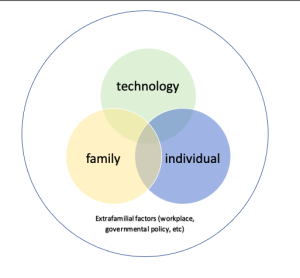

Family Sociotechnological perspective

Lanigan’s socio-technological family model (2009) (see figure below): “acknowledges the effect of multifunctional ICT’s on families and the influence of familial, extrafamilial and individual characteristics on how those technologies are assimilated within the family context.” (p. 595). The model highlights factors of the technology that influence its selection and use, including access, scope, adaptability, and malleability of the technology; obtrusiveness; resource demand (e.g., cost); and gratification potential. Family members are motivated to use technology based on their goals and intentions, attitudes, processing styles, personality (e.g., extroversion, social anxiety), and demographics (e.g., age, gender orientation, education). Family factors are largely represented as demographics, location, stage of development (e.g., transition to parenthood, launching), use by individual members, and family processes. Lanigan roots family processes of cohesion, adaptability, and communication in the model from the familiar Circumplex model of the family. Technological, individual, and family factors are encompassed in the extrafamilial context (Bronfenbrenner’s exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem, 1995).

The socio-technological model can help us better understand “successful” ICT integration in family life. Lanigan observed from her research that “Successful families used the information capability of the technology to enhance family time by learning about community activities and planning vacations and time together…. Less successful families experienced conflict related to the computer. The conflicts resulted from difficulties establishing rules, perceptions that computer use was distancing a family member, and a reduction of family time, communication and emotional bonding…” (p. 604).

Life Course Theory Applied to Family Technology Use

In their 2018 review of the literature on social media and the family, Dworkin et al. observed that frameworks interpreting technology’s impacts on families are limited by not recognizing the impacts of time and context (including social network effects) and in technology itself. They propose the adoption of Elder’s (1998) life course theory to our understanding of the family and technology. The theory emphasizes the role of history on development through time and place, and of life transitions and their developmental impact, with the social networks in which we are embedded conveying the effects of wider macroeconomic and social forces. The individual constructs their path through the life course using personal agency and the opportunities and resources afforded to them. While lifecourse is similar to family development theory in its perspective on lives across time, Aldous (1990) observes that lifecourse focuses more on individual’s interaction with others/groups as they facilitate family event sequences.

Dworkin and co-authors observe life course theory as allowing us to conceptualize change in technology itself as a contextual impact on use by the individual and in turn the family, as well as on the wider social networks afforded by our online and offline interactions — social networks that offer both bonded connections (strong ties) and dispersed, bridging connections to the flow of information and resources. And it allows us to see the individual change in context (including the family context), over time, as introduction to new technologies (whether used or not, and regardless of what degree or by whom) affects internal interactions. Families in the urban U.S. with easy access to high-speed internet, for instance, will be affected quite differently than those in sub-Saharan Africa, where the internet infrastructure doesn’t allow for multiple devices or rapid connection. A life course perspective also aligns well with our recent experiences with COVID-19, as we consider our lives before and after COVID, and workers’ increased desires to work from home and have more flexibility in managing multiple family roles.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework and and approach to social networks and family technology, highlighted earlier in this chapter, lend support to the use of life course theory, and echo the need to see families in a chronological, contextual manner and to visualize the transactional interactions that influence development. As indicated, Chapter 5 will explore Navarro and Tudge’s (2022) adaptation of the ecological model that helps to explicate the person-process-context-time dimensions to explain ICT’s influence in human development.

The chapter ends with a final model that also adapts extant family theory using observations from the virtual world of human communication and interaction — appreciating specific mechanisms of new media and our lives online that exist differently from the real world — and addresses impacts on family structure and processes.

Couple and Family Technology Framework

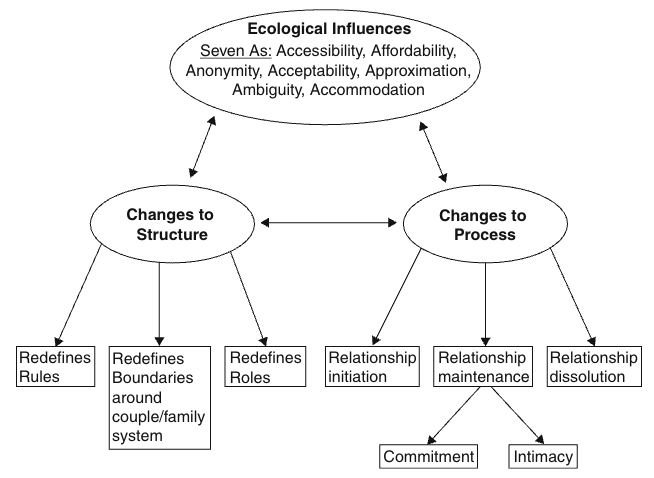

Hertlein (2012) (see also Hertlein, 2018; Hertlein & Blumer, 2013) offers a multi-theoretical model “to describe how technology influences the way couples and families establish rules, roles, and boundaries and interact with each other and the outside world.” (p.375). The model organizes research literature into elements that integrate perspectives from family ecology (how technology as an environment influence affects the family), structural-functionalist theory (how technology affects rules, boundaries, and roles in families), and interaction-constructionist theory (how technology changes intimacy, relationship initiation, and relationship maintenance).

Hertlein’s framework sheds particular light on the characteristics of new media that differentiate them from other forms of communication and relationship interaction, most often assumed to occur in in-person, face-to-face contexts. She calls these characteristics “vulnerabilities” (p. 376), and highlights characteristics of digital media that can shift the perception of communication, the relationship, individuals in the relationship, and intent. The “Seven As” in Hertlein’s model include anonymity (presence online can be masked), accessibility (easier, 24/7 access to the individual), affordability (the lower cost for means of interaction and entertainment), approximation (social presence, or the feel and representation of face-to-face interaction through text and sensory elements), acceptability (e.g., of using technology as the format for relationship communication), accommodation (enabling the individual to behave like their real vs. their ought self), and ambiguity (problematic behavior resulting from time spent online). The structures of the couple and family relationships are influenced through a redefinition of boundaries, roles, and relational rules. Processes of couple and family relationships are impacted through redefinitions of intimacy, and through alterations in how relationships are formed, initiated, and maintained. As Hertlein (2018, p. 90) observes, “the framework considers the context in which the individual is embedded as well as future decisions to use technology and the manner in which technology is integrated into the family.”

Examples of how ICT can contribute to a change in family structure include the power shift as children show parents how to work a new iPhone (roles), a couple renegotiation of what they share about their relationship on social media (rules) and a parent’s distraction by incoming work messages while helping a child with schoolwork at home (boundaries). Accessibility to potential dates through a dating app can change process by helping initiate relationships. Approximation, or the social presence that videoconferencing can convey, can help extended family retain intimacy (thereby maintaining structure) during periods of separation such as COVID or during transnational living. Additional discussion of this framework will occur in Chapter 4 on couple relationships and ICT.

With these family, media, and blended models as a foundation for our critical perspectives on technology as influencing and influenced by families, we now move to a broader scope on family technology use in Chapter 3: differences in use within and across families.