Chapter 4: Technology Use and Couple Relationships

4.1 Technology Use and Couple Relationships

But love is really more of an interactive process. It’s about what we do not just what we feel. It’s a verb, not a noun.

bell hooks

Chapter Insights

- ICT can facilitate communication, connection and intimacy in couples, yet it can also bring out tensions.

- Couples’ use of technology can vary depending on aspects of the couple by member age, age or longevity of the relationships, and stage of the relationship. These couple differences play out in use of specific technology devices, applications, or functions (e.g., sexting, texting, dating apps, gaming).

- Couples differ in their perspectives about the impact of technology on the quality of their relationship.

- Cybersex is a part of couple intimacy, yet can feel for some or members of couples inappropriate.

- Dating apps and online sites are popular ways that couples initiate relationships, whether for a flirtatious hook-up or to seek a long-term partner. There are advantages and disadvantages toward finding a committed partner. There are potential negative impacts to individual well-being, to wider society.

- Accepted guidelines for healthy couple relationship dynamics (e.g., Gottman) can extend to ICT use.

- It’s natural for couples to experience conflict related to technology. More important is how they resolve or prevent conflict as a demonstration of flexibility. Guidelines can be co-constructed for couples to remain cohesive in the face of technology-related conflict.

- Not surprisingly, technology is a tool for perpetrators of intimate partner violence. There are multiple ways that victims can be harassed with ICT. Professionals need to integrated technology into prevention and treatment strategies.

- After reading this chapter, identify what you feel inspired by, the questions that remain for you, and the steps you can take for your own technology use to be more intentional.

Introduction

The developmental exploration of ICT in the family begins with the beginning of families, or when couples first meet (Eichenberg, et al., 2017). It’s not hard to see the many ways in which technology is used in couple initiation — meeting through dating apps; getting to know each other better through social media profiles and messaging, texting, and video conferencing. Whether a family consists only of the two people in the couple, or includes children or other subsystems, couples use ICT in significant ways that maintain the relationship and fulfill family functions. And they use multiple media in their connections, particularly social media and mobile technology.

The growth of research on couple technology use has led to new theories, and to theoretical adaptations of relationship dynamic models that capitalize on the specific affordances of communication through digital media. Use of ICT is now so prevalent in couple communication that the term POPC, for “permanently online, permanently connected” (Vorderer & Kohring, 2013) has been coined. Use of ICT is now so prevalent in couple communication that the term POPC, for “permanently online, permanently connected” (Vorderer & Kohring, 2013) has been coined. These theories address not only new means for communication, but the wide variations in couples.

This chapter will explore ways in which the ages of members of couples, along with the status and length of the relationship, reveal differences in ICT use and impact. A significant portion of the chapter will focus on using technology during couple “initiation,” specifically the use of dating apps and dating online.

Equally important is our examination of technology as a source of conflict in couple communication. To offer a personal example, when my partner goes to a store and texts me to see if we need anything, there’s a good chance I won’t the text in time because my notifications are turned off. This results in his feeling frustrated. Obviously this won’t prompt our heading to divorce court, but our shared use of texting for communication along with our different perceptions of how to use it together present a complexity we didn’t experience before the advent of mobile phones. Conflict can be much more serious, particularly when technology is used to perpetuate intimate partner violence (IPV).

Background on Couple Relationships

Coupling can mean many things, and doesn’t always refer to a serious relationship or commitment. For some, connecting might be a hook-up for sex, serial dating, or casual dating. For others it’s part of seeking a relationship that leads to commitment and a bond that may be legal, cultural, and involve children or shared property.

In the U.S., the rate of marriage has declined from 10.0 individuals per 1,000 in 1986 to an all-time low of 5.1 in 2020. Americans are waiting until later in life to get married, if they marry at all, and “nontraditional” living arrangements are increasingly common. Seen most among Millennials, these changes are due to a variety of factors, including concerns about the economy, women’s education (with women’s advanced education and earning power, they are less dependent on a spouse), and seeing high rates of divorce among their parents’ generation. In terms of finding a partner (for marriage or not), couples cite challenges with increased mobility, migration, dispersal of social networks, longer commutes, and the demands of work and school life.

- Happy couple, by Funk Dooby. CC BY-SA 2.0

- “Couple Talking Through Masks” by Amaury Laporte is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

- parents texting CC by Neil Cummings ND

- “Black Couples are Beautilful lol !” by Khanelle Prod’ Medias is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Healthy Couple Relationships

While there are myriad theories and perspectives on couple/marital relationships[1], for efficiency we’ll focus on principles from two perspectives.

John Gottman’s research[2] on sound couple relationships uses the analogy of a house, with trust and commitment as the “weight-bearing walls.” At the foundation, the building of “love maps” is a process of getting to know each other, ideally better than others do. On the second “floor,” partners share admiration and fondness for each other, each telling the other what they like about them. On Floor 3 they turn toward one another, not away. This includes knowing each other’s cues for response and attending to them. On Floor 4, working on positive perspectives of each other and themselves in the relationship, partners offer compassion and understanding rather than criticism. Floor 5 involves managing conflict when it arises — accepting the partner’s motives, discussing programs, and practicing self-soothing. On Floor 6 they make dreams come true for themselves, the other person, and the couple as a unit. And at the top, Floor 7 finds couples creating shared meanings through rituals, ceremonies, pet names, memories, and so on — things that identify the two people as a defined unit.

Gottman’s principles easily relate to the discussion of family processes in Chapter 2. Communication aids in relationship processes, fulfillment of roles, and reinforcement of relationship structures, and over time, communication and connectivity aid in relational cohesion. Because the couple, like the family, is an open system, external influences (like the availability of a smartphone during face-to-face conversation) can facilitate conflict, so it is important for partners to show flexibility in adjusting to and accommodating each other’s needs and keep focus on the relationship. Gottman’s own institute offers online resources for couples, including a relationship “check-up.”

Another perspective blends research, including Gottman’s, to characterize couple relationship skills that are predictive of satisfaction and well-being. A review of the research identified skill areas (Futris et al., 2013) which were later were developed into an inventory of relationship quality: the Couple Skills Relationship Index [CSRI] (Adler-Baedler, et al., 2022).

The skill areas of the inventory include:

- Self-Care (originally titled Care for Self): efforts to promote individual health and well-being

- Choose: attitudes and efforts related to intentionality and prioritizing the relationship

- Know: attitudes and efforts that promote intimate knowledge between partners

- Care: attitudes and behaviors that promote other-oriented positivity

- Share: attitudes and behaviors that promote a sense of couple solidarity and “we-ness”

- Manage: attitudes and skills for managing stress and conflict

- Connect: attitudes and efforts to embed the couple relationship in support networks (Adler-Baedler, et al, 2022 p. 282)

Jointly, these areas reflect a conceptual framework built on the foundation of a variety of social, ecological, and learning theories applied to couples, predictive of positive relationship quality (e.g., positive feelings, satisfaction, family harmony). Going forward, we’ll explore how ICT is used to convey couple relational dynamics and influence relationship well-being.

As we explore research findings on this topic, a caveat. While significant research on couples and ICT has been completed by the time this book was written (2022), it remains limited. Not all forms of ICT have been studied nor studied to the same degree. Great focus, for example, has been given to dating apps and to texting as a process of communication, and less to videoconferencing, videogames, or virtual reality. Research samples struggle to reveal couple demographic or global diversity, though there is a certain presence of queer couples in published literature. Research on age and couple longevity tends to focus more on younger couples and those in the early throes of a relationship, look at those at the dissolution stage, and explore how ICT can help couples communicate and coordinate around the needs of their children. Couple research is thus ripe for more investigation, particularly as devices and platforms for engagement evolve (including virtual reality dating) and as we further understand potential security pitfalls and privacy threats from individual error (e.g., sharing information about a partner online they intended to keep quiet) and data mining. For the most recent research, readers are encouraged to do Google Scholar/EBSCO or other searches for specific topics, platforms, couple types, and processes of couple relationships.

Advancing Relational Theory with Regard to Digital Technologies

In Chapter 2, we noted that extant theories of family life can help us frame family processes that contribute to well-being, and examine internal and external influences on those processes in our current age of technology use. To be sure, the focus should be less on the descriptive use of ICT by families and more on what these tools and interactions mean to family dynamics and outcomes. Newer theories are being developed to adapt extant frameworks of the family to new technologies.

The Couple and Family Technological Framework (revisited)

Hertlein’s research on the ways in which couples used technology identified benefits to relationship initiation and management, along with challenges such as distancing and ambiguity (Hertlein & Ancheta, 2014). This informed the family technological framework (Hertlein & Blumer, 2013) discussed in Chapter 2. Relationship communication via the “mediated affordances” of ICT (e.g., anonymity, access) can affect perception and understanding of relationships; couple conveyance of rules, roles, and boundaries; and couple relationships as a shifting structure (e.g., from initiation to maintenance). Hertlein’s model has been used to examine a range of couple and family situations, including parenting, videogame playing by couples, and sexual infidelity. A cogent explanation of the 7As applied to sexual dysfunction is presented in Hertlein et al., 2017.

Relational Maintenance

Theories focused on interpersonal relationship dynamics abound in the literature on computer-mediated communication (CMC); many are discussed by Walther and Parks (2002). Some theories explore relationship components and ICT use, including relationship development, perception, and contexts for interaction. Mason and Carr (2022) present an excellent overview of the work to adapt relational theory to the realities of digital technology, and suggest elements to consider in using online technologies to maintain off-line relationships. As with Hertlein and Blumer’s model, they evoke the characteristics and “mediated affordances” of ICT as actors in relational dynamics. With a foundation of social penetration theory (Altman & Taylor, 1973), which posits that the reciprocal exchange of information, processed by relational partners over time, helps progress closeness, Mason and Carr describe six dimensions of digital communications that influence relationship maintenance:

- Lightweight interactions: Instant messaging and social network communication offer brief but frequent exchanges. Yet as the authors observe, given the social exposure and potential for miscommunication, they may come with a cost: “lightweight interactions may be capable of sustaining less developed relationships but understanding its role in more developed relationships might prove more complicated” (p. 250). And while those in close relationships may use multiple media (e.g., media multiplexity), there is evidence that the topic and quality of information across these devices is replicated.

- Nature of disclosures: Methods of sharing online can be ephemeral (as in Instagram stories), and what is intimate seems up for interpretation. The overly social atmosphere of online spaces has led to the need to determine what information is personal and what is interpersonal.

- Mass personal spaces: Conveying personal messages in wide social spaces can seem less intimate, given that they are on a platform shared by many, even when messaging is “private.”

- Social presence: the sense of being with another person even though they are not nearby. ICT modalities allow for sensory and text-based mechanisms for partners to feel the presence of the other.

- Ambient awareness occurs when individuals receive messages broadcast by others. In a relationship, this allows for the passive observation of information about the other person. Viewing a partner interact frequently with another, for example, can lead to feelings of rejection.

- Algorithmic proximation: As Mason and Carr (p. 257) succinctly observe, considering online interactions, “individuals in a particular relationship are not the only actors who may influence relational outcomes. Online information distribution and display are now substantively controlled by sophisticated algorithms.”

These elements are observed in richer detail as some of the research on how ICT operates in couple relationships is discussed throughout the chapter.

Technology Use by Couples

With the majority of U.S. households having access to the internet and owning smartphones (U.S. Census, 2021), and rates particularly high in households with younger heads, in urban areas, and across all socioeconomic strata, texting is a key method of communication between couples. As with others motivated to use technology, couples cite efficiency, ease of use, and mobility (Nylander, et al., 2012). Calls and texts enable couples to express affection, forge intimacy, solve problems, and gather information. Couple duration, closeness, and familiarity with using cell phones as a communication device are predictors of positive and continued use. Social media is a mechanism for some couples to communicate about their relationship (Anderson & Vogels, 2020) and to learn more about potential partners. Videoconferencing, virtual reality, and augmented reality offer sensory mechanisms for greater presence. During COVID-19, the news ran a story about an elderly couple who kept in touch using FaceTime, as one resided in assisted living. Other uses of more sensory mechanisms of mediated communication include cybersex, or sex-related interactive behavior that includes viewing pornography, sexting, and web-cam sex.

In a qualitative analysis of college students, with about half in long-term relationships and others in casual relationships, Hertein and Ancheta (2014) identified themes in technology use by relationship initiation, management, and enhancement. Relationship management included technology for seeking information, managing conflict, reducing anxiety, and demonstrating commitment. Relationships were enhanced by using technology to spice up sexual relationships and stay connected when separated by distance.

If a researcher asked you if technology impacted your relationship, what would you say? Might you want the researcher toTechnology’s “impact” on couple relationships depends on the couple’s perspective on what impact means. define what they mean by “impact”? In 2014 research by Pew (Lenhart & Duggan), couples viewed “impact” as something fairly significant, as only 10% of long-term couples (defined as those together for 10 years or more) reported that technology use had any impact, and that impact was positive, with many citing increased connectedness. Higher rates were found in younger age groups, with 21% of those age 18–29 reporting that technology had a major impact. A more recent study from Pew (Vogels & Anderson, 2020) also found little impact from couples viewing others’ posting about their relationships on social media. Although 81% reported seeing what others post about their relationships, within that group most (81%) said it didn’t make a difference in their own relationships, and another 9% said they felt better about their relationships.

There are downsides to using technology in couple relationships, of course. Misunderstandings and differences in use are common. Couples sometimes experience an imbalance, with one partner using a device or application in ways that don’t include the other or to a greater extent than the other. Videogaming, viewing pornography, even “phubbing” — ignoring the partner while with them by focusing on a phone — can create conflict. Technology is sometimes also used to assert an imbalance of power — to a lesser degree, by choosing to hold difficult conversations (or even break up) online rather than in person, and in extreme cases when stalking, harassing, and withholding a partner’s access to technology, as seen with intimate partner violence. The sections below will offer a closer view of couple use, misuse, and impacts.

Differences in couples

Like families, couples have a developmental trajectory and develop over time and in stages. Couple relationships can be defined by time (or length of the relationship) and by stage. Are the partners just meeting? Making a formal commitment? Transitioning to childrearing or another adult life stage, such as home shared ownership? They might be at the end of the relationship and experiencing formal separation or divorce. And couples vary by the age of the individuals. They might be teenagers, young adults, older adults, or seniors, the same age or different ages. And naturally, as with families and individuals, couples can be viewed by ethnicity, race, religion or culture, geolocation, age, gender, health status, education and income, and other demographics. These factors, along with the myriad other factors that influence individual use discussed we’ve so far, can influence how technology is used, how it is viewed as a tool in the relationship, and its impact on the well-being of the relationship.

By age of couple members

Younger couples use digital communication in relationships differently than older couples. Teenagers in relationships, for example, use technology for communication and daily check-ins; they report that the immediacy of contact can enhance feelings of intimacy, and that delays can lead to negative feelings, especially when the partner is otherwise visible (Commonsense Media, 2015). They acknowledge that their use of technology in the relationship can breed possible miscommunication and discomfort from feelings of surveillance by the partner, feelings of jealousy, and the potential for boundaries to be blurred.

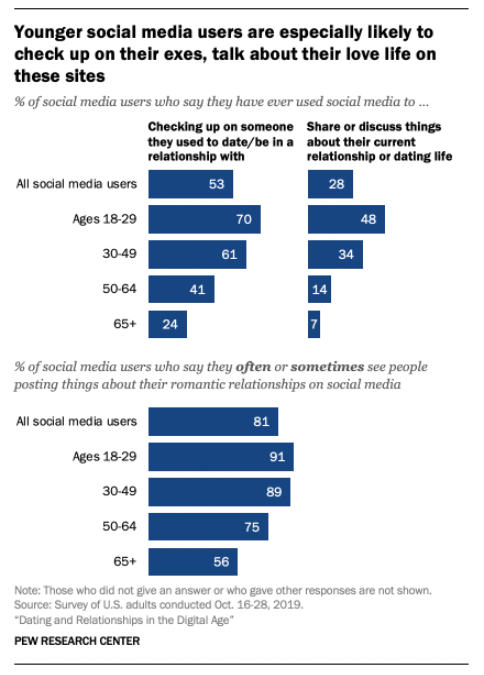

Though only just over a quarter (28%) of adults who use social media use it to share about their relationships, frequencies vary greatly by age. Nearly half (48%) of adults 18–29 years indicate that it is important to show how much they care about their partner, compared to 10% of those 50 and older. Younger social media users say it is a way to publicly demonstrate affection for their partner, and be aware of their partner’s life (Anderson & Vogels, 2020). Interestingly, non-white couples and LGBT couples are more likely than white and straight couples, respectively, to use social media in this way. Those who are younger are also more likely to see others’ post about their relationships on social media. Compared with 91% of adults age 18–29, 75% of those 50–64 indicate seeing others post about relationships.

Younger adults using social media are also much more likely to check up on exes. While 53% of adults on average report using social media this way, the frequency reaches 70% among those age 18–29. Not surprisingly, a greater proportion of younger adults also report feeling jealous and unsure about their relationship due to their use of social media (34% vs approximately 16% of adults over 50).

By length of the relationship

Long-term couples tend to view and utilize technology quite differently compared to those who have been together for a shorter period of time. In part this is due to couple member age — couples together for less time are more likely to be younger and are familiar with the use of technology for relationship logistics. Shorter-term couples may also be more sensitive to miscommunication prompted by online formats. Relationship length can moderate negative couple outcomes associated with frequency of Facebook use and Facebook-related conflict (Clayton et al., 2013). And longer-term couples may use technology together — sharing email or Facebook accounts — since they were together at the advent of the Internet and social media. Couples who have been together for less time reported feeling closer to the partner due to online or text messaging conversations, they resolved an argument with the partner online or by texting, and they texted the partner while at home together.

By stage of relationship

More established couples use technology to communicate conveniently, seek information, manage conflicts, reduce anxiety, and demonstrate commitment (Hertlein & Anchleta, 2014). They also try to spice up their sexual relationships, and stay connected during distancing separations. The sharing of sensitive information such as passwords or accounts is a key difference by relationship status. Although the majority of couples in relationships indicate sharing a password for a cellphone (75%) or email account (62%), those who are married or living with a partner are far more likely to do so than those in committed relationships. In the case of email accounts, for instance, 70% of those who are married share accounts, compared to 22% of those in relationships (Anderson & Vogels, 2020).

Divorced and separated couples (with children)

Beyond the use of technology to file for divorce (Eichenberg, et al., 2017), or apps to help newly solo parents manage practical challenges after the divorce, technology and communication between separated and divorced couples is a dominant focus for family professionals. Research examines differences in what is used, how, and by whom, e.g., texting, email, and social media (Dworkin, et al., 2016; Russell, et al., 2021, Smyth, et al., 2020). Russell et al. (2021) identified a typology of mediated communication in post-divorce couples with minor children: those extensively using multiple media, those who mixed face-to-face communication with phone calls or texting, minimal communicators relying largely on texting, and very limited communicators using occasional texting. The selection of type of media, frequency, and use relative to desired intent varies. Couples may, for example choose email for more lengthy communication, to share documents, and in cases of conflict (Ganong, et al., 2012), and choose asynchronous forms of communication. Divorced parents may also be more likely to use technology to communicate with and through their children rather than directly communicating with the co-parent (Dworkin, et al., 2016).

In Russell et al.’s (2021) research, divorced couples who use multiple methods of communication were more likely to rateas cooperative partners, while those using more limited methods, and who had limited contact, rated higher as “dissolved duos” or “angry associates.” This reinforces Ganong et al.’s (2012) early conclusion that use and quality of communication in couples post-divorce is dependent on relationship quality (amicable or contentious). Social presence theory may account for the differences in technology selection, with more adversarial couples choosing to be less present through digital media. In tracking high-conflict Australian couples post-divorce over a five year period, however, Smyth et al. (2020) found shifts in technology use, including the use of multiple media, synchronous and asynchronous methods with ex-spouses, and shifts in frequency and intimacy. They questioned whether technology selection in divorced and separated couples may be less static than previously understood.From a legal standpoint, couples may be wary about how they communicate, as digital communication can be archived, retrieved, and used in litigation.

Some divorcing/divorced couples use technology used in adversarial ways. Text messages, apps, and social media accounts are used in evidence in divorce cases. At least one family law firm offers a guide for digital communication and divorce. In many states, post-divorce couples education is mandatory; hopefully it addresses the use of technology in partner and child communication. Some states, such as Texas, require divorced couples to use particular apps to pay child custody or communicate with the partner and children, but non-compliance appears to be an issue.

Video Watching, Gaming, and Cybersex

In addition to texting and the use of social media, technology is used by couples (or by one member of the couple, influencing the other) in additional ways that have an impact on the relationship. This includes watching videos, videogaming, and participating in some version of cybersex, which can include sexting, viewing pornography, or webcam or AR/VR sex. Interestingly, most of these activities are ones couples report doing in their bedrooms — a location with sociocultural importance to intimacy and privacy (Salmela et al., 2019). As with more generic uses of technology for communication in couples, these applications bring both benefits and challenges to the relationship. As with more generic uses of technology for communication in couples, watching videos, gaming and forms of cybersex applications bring both benefits and challenges to the relationship.Gaming, for example, can generate closeness through the sharing of an activity, yet it can generate conflict when one partner is into gaming and the other is not. And sexting can offer a specific type of intimacy, yet have ramifications when used improperly (e.g., as underage pornography, as infidelity).

Video watching

Just as when families co-view media together (Padilla-Walker et al., 2012), couples can feel a greater sense of connectedness and cohesion when they watch TV, movies, and videos together. (NOTE: This isn’t to be confused with “Netflix and chill.” Today the phrase is more of an analogy for having sex.) Recently, viewing videos on TikTok has become a shared activity for couples. Co-viewing media can involve watching together in person, co-viewing separately but at the same time, and viewing common media and texting about it or posting to a social media account the other person follows closely.

This piece in the popular press cites a psychologist’s take on making a long distance relationship work as a “TikTok” couple. While research isn’t cited, the conclusions are reasonable given research on couple emotional contagion, social connectedness, and cohesion (Zilich, 2020). Sharing the platform may put couple members in a good mood and/or lower stress levels, give them a cooperative task that allows them to problem solve and create a joint project (such as doing a “Flipped the Switch” dance video), share an emotional experience (and talk about it), and take a break from their usual routine. This might be especially valuable during long periods of time under restriction, such as COVID-19 or bad weather.

Gaming

Gaming can be a source of connection, allowing partners to share an interest and a source of intimacy. According to the Entertainment Software Association (ESA), in 2021, 42% of videogame players played with a spouse or partner; another 23% reported meeting their spouse or partner through playing videogames. Giving its popularity and accessibility, gaming might be a way for adults with a disability to make connections with others with shared interests. During COVID-19, videogames were especially popular with couples during the long months of quarantine. While most (57%) use a smartphone or a gaming device (46%), those using a smartphone are more likely to play casual games like Tetris, whereas those on devices will play action games. As we’ll discuss in Chapter 9, videogames are also popular with families, and as a way for parents to monitor their children’s online time and to model safe use.

For most couples, game playing has a neutral effect on the relationship (Coyne et al., 2012). Challenges are possible when one partner’s time playing upsets the other’s expectations for time spent together. Some couples experience conflict over the time spent by one member, particularly if it means exposure to others who present a threat to the relationship. In some cases, partners identify aggression brought out by gaming as a source of conflict in the relationship.

Smith (2012), in research on attachment behaviors in committed couples based on perceptions of partners’ videogame use, reports that the male’s violent videogame use and the female’s nonviolent videogame use predicted the perception and that videogames were a problem in the relationship, and this perception predicted less attachment behaviors, which was a fully mediated relationship for both. The female’s view that videogames were a problem negatively predicted both her and her partner’s attachment behaviors, while the male’s view only predicted his attachment behaviors.

Cybersex: Sexting/Cybersex and Pornography

Online sexual activity can influence the couple relationship. When conducted together, online sexual interactions — whether exchanging sexts or viewing online pornography together — enables couples, sometimes geographically separated, to experience greater intimacy in their relationship. Necessary distancing during COVID-19, and concerns about the transmission of disease including sexually transmitted disease, led the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (2020) to state, “The new ‘really safe’ sex in many cases may require ‘e-sex.’”

Definitions of cybersex vary widely. Beyond sexting, the exchange of sex-related materials, and viewing pornography alone and as a couple, it can also mean use of augmented reality or VR, and of sex-robotics, anticipated to be a future trend (Döring 2017). A review of TMSI (technology-mediated sexual interaction) by Courtice and Shauggnessey (2017) indicates that research in this area tends toward the negative (e.g., cybersex addiction) rather than taking a more neutral approach to studying the behavior. A small portion of individuals develop cybersex addiction (Giordano & Cashwell, 2017, suggest 10%), yet Eichenberg et al. (2017) observe that much of the research is self-reported and that many using the internet for sex don’t see their use as a problem, so accuracy in prevalence is hard to gauge. And critical consensus of the research finds it lacking (Banerjee & Rao, 2021; Courtice & Saughnessey, 2017). Banerjee and Rao (2021, p. 7) observe:

Besides cross-cultural and cross-country, research should focus on cultural effects on virtual sexuality and effects of cybersex on psychosexual health. Longitudinal mixed-method studies and exploring lived experiences related to partnered and solo sex are essential to formulate policies and guidelines that can be rooted within the participant perceptions.

Because if we are moving toward more than increasing our understanding of family life through research, to practice and policy, including requirements around consent between couples, it is essential that the work be both rigorous and representative of the phenomenon as facilitated by cyber-technology.

Sexting

While sexting — sending sexually provocative texting or images via digital technology — is not an activity that the majority of couples participate, it represents normative couple behavior and intimacy and is present in a significant minority. Research with 615 demographically representative couples in the U.S. and Canada revealed that most (71%) didn’t sext, 14.5% were “word” sexters, and 14% were frequent or hypersexters (Galovin, et al., 2018). In that study, sexters were more likely to be younger (though older than adolescents) and homosexual, and to use media and view pornography. Pew research in 2014 similarly revealed sexting in younger age groups. Those between 18–24 were most likely (44% of the subsample) to receive sexts, whereas those 25–34 were most likely (22% of the subsample) to send sexts. That said, occasional reports in the media single out individuals such as Anthony Weiner, a former New York congressperson who was given 21 months in jail for sending sexts to a 15-year-old, or cases of a school teacher or coach. Sexting is also related to couple duration and stage. Those more likely to receive sexts are those who are single, those not in a relationship or those whose relationship is 10 years or less.

A meta-analysis of sexting research (Kosenko et al., 2017) found a positive relationship between sexting and sexual activity, having unprotected sex, and number of sexual partners. Galovin et al. (2018) determined that relationship satisfaction among sexters wasn’t significantly different from non-sexters, though they were more likely to express sexual satisfaction in the relationship. Other relationship variables for sexters were less positive, in measurements of commitment, ambivalence, and conflict.

Still, partner context appears to matter greatly. Those in trusting, safe relationships (whether gay or straight) may have a different sexting experience than others. And Courtice and Shaughnessey (2017) indicate that relationship impact research is so variable that it’s difficult to offer firm conclusions.

One aspect of sexting that is not variable is the existence of state pornography laws. Each state has laws around sexting, particularly around sending or receiving messages to a minor or a person under the age of 18. These laws can catch individuals unaware; for example, an 18-year-old sending a picture of a 16-year-old is considered pornography. Non-exclusive factors that determine if “a visual depiction of a minor constitutes a ‘lascivious exhibition of the genitals or pubic area’” under 18 US Code §2255(2) (E),4 the definitions section of the statutory scheme (Id. at 830),” include:

-

whether the focal point of the visual depiction is on the child’s genitalia or pubic area;

-

whether the setting of the visual depiction is sexually suggestive (i.e., in a place or pose generally associated with sexual activity);

-

whether the child is depicted in an unnatural pose, or in inappropriate attire, considering the age of the child;

-

whether the child is fully or partially clothed or nude;

-

whether the visual depiction suggests sexual coyness or a willingness to engage in sexual activity; and

-

whether the visual depiction is intended or designed to elicit a sexual response in the viewer (Id. at 832). (Strassberger, et al, 2019).

It is essential that teenagers and those who may be in relationships with teenagers are acutely aware of state laws regarding the sending of sexts to underage minors. Sexting and adolescents is discussed further in chapter 5.

Viewing pornography

Pornography viewing is another mechanism for potential couple satisfaction, particularly as it might enhance foreplay. The internet makes it easy to find just about any type of porn, while also ensuring certain anonymity. It’s reported that 25% of all internet searches relate to pornography, as do 35% of all internet downloads. Yet viewing pornography may also lead to conflict, particularly when one partner views it in the absence of the other (Gingrich, 2017).

Men are more likely to view porn than women. A study from the Wheatley Institute examined heterosexual individuals and paired couples in committed relationships, (defined as seriously dating, cohabiting, or married; Willoughby et al., 2021). There were clear gender differences about viewing hard-core pornography (defined as featuring depictions of actual sex acts that display full nudity), with men either married or never married reporting nearly double the frequency as women. Married (51%) and dating (36%) women reported never viewing pornography at higher rates than men. Younger men (under 30) were also more likely to view pornography. Other research supports these gender differences in pornography viewing in couples. Unmarried men and women in couples report viewing porn at about the same frequency. It’s interesting that men and women aren’t very good at estimating what the other does. Whether it’s viewing hard-core or soft-core porn, women underestimate the percentage of men who view it, and men overestimate rates of women as viewers.

Across all gender and couple status groups, attitudes toward viewing pornography were positive in the Wheatley study for the majority (about 80%), particularly when asked about viewing as adults (whether married or unmarried). Far fewer individuals were positive about teenagers viewing porn. More men than women also saw viewing porn as helping foreplay (50–60%, depending on couple status, compared to 40–50%).

Does viewing pornography introduce conflict to the couple? Or might it positively contribute to couple intimacy, particularly since sexual satisfaction is a component of a happy relationship? Reviews of the research show mixed results (Webster, 2022). There is evidence that supports that viewing pornography together positively contributes to couple satisfaction. In the Wheatley study, couples who did not view pornography had high ratings on measures of stability, commitment and relationship satisfaction. Ratings were positive yet lower in couples who did view pornography, and lowest for those who did not view it together and when porn viewing by a partner was frequent. Sexual satisfaction was rated similarly whether or not couples viewed porn.

In the Wheatley study, about 20% of couples said viewing pornography contributed to conflict. In a 2021 US study, a minority of couples report that viewing pornography (alone or together) contributed to conflict. Men may hide their viewing (identified in about 25% of the sample), a partner’s viewing may bring out insecurities in the other, or viewing may signal that there are issues in the relationship that are not being discussed. Webster (2022) observes that couples in conflict may turn to pornography as a way to avoid conflict. On the data that correlates viewing with marital dissatisfaction, Webster (2022) and Gingrich (2017) observe research limits identifying the direction of the relationship: do those who have poor relationships turn to porn, or does viewing porn contribute to poor relationships? Considering homosexual and heterosexual couples, couple impact of partner viewing of pornography (the man in a heterosexual relationship) depends on context (Gingrich, 2017). Viewing porn can affect men’s feelings of intimacy, sexual satisfaction, and perception of sexual freedom with partners when men have a positive level of partner disclosure. Attachment level also appears to matter. Men with insecure attachment may turn to viewing pornography as a way to disengage and avoid perceived challenges with partners.

Technology-Related Conflict and Resolution

While ICT can enhance communication efficiency and personal connectedness, it’s clear that it can also produce conflict for couples. Consider a possible conflict that might arise between a couple. How might technology relate to that conflict, and how does it influence the couple’s relationship? Whether it’s looking at a partner’s phone, checking on exes through social media, or feeling jealous or underconfident in the relationship based on the partner’s social media use, younger adults are more likely than those in other age groups to report these challenges, as are those who are not married but in relationships. Hertlein and Ancheta (2014) identified themes in couple interference and technology that will be used to structure this section. The themes are validated by the work of other researchers exploring couples’ technology use (e.g., Vaterlaus and Tulane’s study of married couples, 2019).

Issues observed

Distancing

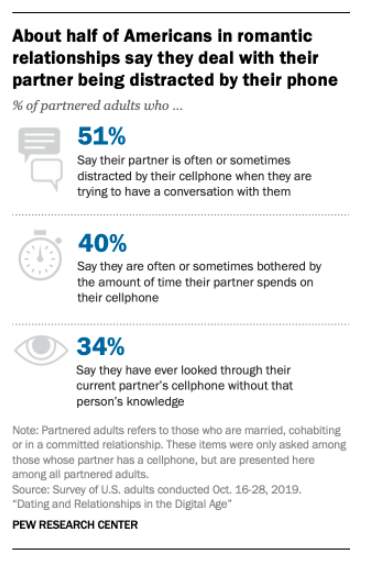

Messaging by text or by sext can seem impersonal to some, removing the individual’s self and interest in the communication. Phubbing in couples (also labeled PPhubbing, or Partner Phubbing), a type of technoference (McDaniel & Coyne, 2016) has been widely studied. As indicated below, even among married and committed couples, over half indicate that their partner is distracted by their phone. Nearly as many report feeling bothered by the amount of time spent on the phone.

Negative effects of phubbing in couples include perceived effects on intimacy, reduced relationship satisfaction, reduced sexual satisfaction, diminished sense of quality time, and effects on partner mental health. Wang et al. (2019) examined married couples in China and found that phubbing related to depression and negatively related to relationship satisfaction. There was also an indirect relationship to depression based on the impact on satisfaction, meaning that as a partner’s satisfaction in the relationship decreased due to phubbing, they felt depressed.

Another study with married couples in China (Chen et al., 2022) looked at the transmissive effects of phubbing, or one partner ignoring the other after they have been ignored. It is fairly common for couples to pick up each other’s behavior due to their interdependence and time together. The Wang et al. study found that men were likely to start phubbing when their wives did it, but women were not. The authors observed that this could be an effect of gender role socialization. This study also validated the connection between phubbing and relationship satisfaction, but demonstrated that lower satisfaction was an influence on phubbing.

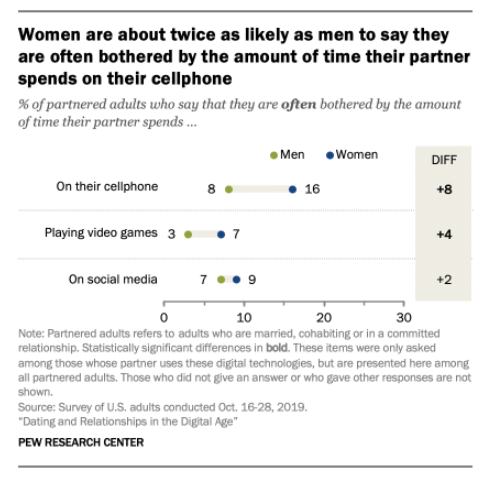

Women in the U.S. are more bothered than men by being ignored. While percentages are rather low overall (16% being the highest of all groups), for all media — phones, social media, and videogames — women are more likely to report feeling dissatisfied when their partners are on these devices.

Long-term German couples, ranging in age from 29–72 and averaging 22 years together, were studied for personal (attachment anxiety), gender, and relationship influences on phubbing (Bröning & Wartberg, 2022). The behavior was more likely in younger couples. Authors interpreted this as the long-term couples being stable in their relationships, communication, and coping and conflict resolution patterns. Attachment orientation was highly correlated with phubbing perceptions. In other words, long-term couples that have developed an increased sensitivity toward each other due to an insecure attachment orientation may perceive phubbing as more damaging to the quality of the relationship.

Couples can also avoid issues by focusing on their phones, or address challenging topics by asynchronous text rather than having a face-to-face conversation. Even having a phone out while spending time together can feel like a distraction and interfere with the feelings of intimacy (Turkel, 2015).

Impaired trust/Breaking boundaries

Couples indicate that it’s easy for their partners to hide texts or sexts to others, and to hide online activity, including social media (e.g., following an “ex”). This can create concerns over infidelity, also called “digital jealousy” (Eichenberg, et al., 2017). It should be noted, however, that definitions of infidelity using the internet are somewhat “messy,” to use Vossler’s (2016) term. Some common factors include attempts toward privacy, using access and anonymity features of the internet, and abrupt discovery. Vossler’s review suggests that couple impacts of cyber-infidelity are similar to those from infidelity offline: partner distrust, relationship conflict, and potential dissolution.

Couples, especially younger ones, may use social media to gather information about their partner’s activities. And as social media is a popular way to check up on exes, knowing this can lead existing partners to feel jealous or suspicious.

Looking at a partner’s phone or social media account can break boundaries, and doing so without permission is a sure way to damage trust. Regardless of age, commitment status, or other demographics, nearly ¾ of couples (71%) agree that it is not appropriate for a partner to look through another partner’s phone without their knowledge. Still, one-third (34%) of couples admit to doing so (Anderson & Vogels, 2020).

Lack of clarity

The final area of challenge for couples is lack of clarity. As we’ve discussed, users vary widely in their access, attitudes, comfort, and skill related to technology. One partner, for example, may spend more time on their phone and frequent social media, while the other tries to avoid social media all together. Differences in texting patterns, especially, can contribute to miscommunication. When a message isn’t returned, or is returned late or with an ambiguous wording, a partner can question the motivation or misinterpret the message (Vaterlaus & Tulane, 2019). Ambiguity in text messages is a common issue, as is the use of emojis (Miller et al., 2017). When couples get into significant issues through texting (e.g., confrontations, apologies), one or more members can feel uncomfortable (Novak et al., 2016).

Talking about it

Most couples don’t discuss social media use as a possible relationship issue, though individual partners may have implicit rules that need to be discussed. Digital jealousy appears not to be medium-specific, and is dependent on individual couple perception of cheating (Eichenberg, et al., 2017). Interview research with committed couples regarding technology use as integrated into daily life offered a process model of how boundaries and rules are negotiated (the definition of “committed” was left up to the couples; no time length or status marker was supplied by the researchers; Pickens & Whiting, 2019; Cravens & Whiting, 2015). The authors suggested that professionals, understanding this process, can offer suggestions to help couples with conflict resolution.

- Step one: identify the online issue, including past issues or inappropriate behaviors

- Step two: appraise the online issue, implicit rules, explicit rules, and rule consensus

- Step three: discuss the online issue, providing evidence, justifying the behavior, or explaining the perspective

- Step four: achieve resolution for monitoring and successful communication, or explore consequences that might lead to breaking up

Couples might want to ask:

- Are there any websites that you believe would be inappropriate for me to visit?

- When I use a social media site, are there groups of users or specific people with whom you would be uncomfortable with me interacting?

- Is there any information you feel should or should not be posted online about me you or our relationship?

- Do you consider pornography to be a violation of our relationship?

Couples therapist Veronica Marin (2017) offered the following relationship tips:

- Make your partner feel more important than your phone, spending at least 20 minutes a day of screen-free time together.

- Check in before posting anything about the relationship.

- Set expectations for texting.

- Comment online as though in real life.

- Don’t snoop on a partner’s behavior; give your partner the benefit of the doubt when, for example, they’re friending an ex.

- Address discomfort quickly. If a a partner is snooping or microcheating, discuss reasons rationally.

Serious conflict: Intimate Partner Violence and technology

Cyberstalking, psychological abuse, technology restriction, and technology-facilitated sexual violence are forms of intimate partner violence with technology, or tIPV (Duerkson et al., 2019). Cyberstalking can include sending threatening messages, selling or purchasing items online in the victim’s name, pretending to be someone to communicate with the victim, and creating a webpage or advertisement with the victim’s information. Using multiple media in stalking creates the sense of what Woodlock (2016) calls “perpetrator omnipresence” (p. 592).” Cyberstalking can include sending threatening messages, selling or purchasing items online in the victim’s name, pretending to be someone to communicate with the victim, and creating a webpage or advertisement with the victim’s information (Eichenberg et al., 2017). This can cause isolation, humiliation, and fear. Affordances of the internet, texting, and social media enhance the cyberstalkers’ ability to track others and access user preference data, and provide anonymity. Using multiple media in stalking creates the sense of what Woodlock (2016) calls “perpetrator omnipresence. (p. 592)” Online stalking can continue for long periods, and the ability to separate from stalker contact is challenging for victims.

tIPV is prevalent among victims of intimate partner violence. A review of records from survivors of IPV between 2012 and 2016 revealed that 60–63% indicated technology-related abuse (Messing et al., 2020). Yet tIPV is also not clearly or consistently defined, and domestic abuse agencies may not yet recognize the power or potential of technology to produce consequences to the victims similar to those that take occur IRL. Assessing technology-based abuse, Messing et al. asked: “Has your partner used technology or social media to monitor your interactions with other people?” and “Has your partner used technology or social media to monitor your whereabouts?” and in a separate sampling, “Has your abusive partner used technology to harass, stalk, impersonate, watch over or threaten you?” While their quantitative analysis offered statistics, their qualitative analysis illustrated the subjective nature of online behavior that can muddy the ability to assess it. For example, some may refer to monitoring as stalking, while others relate it to a neutral or loving motivation (e.g., ensuring safety after a drive in dangerous conditions).

In a survey of Canadian college students, Duerksen et al. (2021) looked at predictors of tIPV. Social media was more prevalent as a medium for perpetrating violence, as it offered more ways to harass a victim, although it is also riskier in that it’s more public. The researchers also found that in-person harassment and technological disinhibition were predictors of tIPV. The authors suggested that rather than technology creating more aggressors, it gives those with the propensity to stalk and harass additional means, particularly those comfortable with using technology.

The prevalence and likely increase in the use of technology for IPV requires that agencies and professionals working in this area integrate ICT in their strategies for prevention and treatment. The Canadian government includes technology-facilitated violence in its list of types of IPV. Others also offer guidance. As Woodlock (2017, p. 399) observes, “If women are to use mobile technologies safely, technology-facilitated stalking needs to be treated as a serious offense, and effective practice, policy, and legal responses must be developed to address the use of technology as a tactic for abuse.”

Dating Apps and Online Dating Sites

- “Dating Apps On Mobile Phone” by Norma Dorothy. CC BY 2.0

- “grindr” by meliesthebunny is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

- “Ashley Madison 74%” by thelampnyc is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

People have long sought assistance in finding a romantic partner (Schwartz & Pellotta, 2018). Family and religious institutions have played matchmaker, and arranged marriages continue in some cultures and are even popularized as reality television (see, for example, Netflix’s Indian Matchmaking). Friends offered introductions, and clubs or religious gatherings were convenient ways to find and vet partners. Adventurous seekers used to place personal ads in print newspapers (e.g., “single white female ISO single mixed-raced male”). In the 1980s, video cassette recorders (VCRs) enabled videodating, with people recording personal ads.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0bomkgXeDkE

Early research indicated that online technologies facilitated couple connections through shared interests (such as through virtual gaming; these are naturally forming connections), networked friends (networked relationships), intentionally sought relationships (targeted relationships), and digitally assisted relationship initiation, such as meeting in person then continuing online/through text (Sprecher, 2009). With the advent of the internet and social media, sites such as eHarmony and match.com and matchmaking services like It’s Just Lunch offered efficient and somewhat tailored connections to others. And Grindr, an app for gay men, streamlined mate selection among the early dating apps developed around 2009 (Schwartz & Pelotta, 2018).

Eichenberg et al. (2017) identify different formats for finding dates online (p. 250):

(1) single exchanges where flirt contacts dominate,

(2) partner exchanges which correspond most closely to the traditional contact advertisement,

(3) erotic dating/casual dating portals that aim to provide non-binding sex contacts,

(4) niche providers, i.e., specialized platforms with the objective of connecting people with specific interests and preferences, and

(5) social dating (e.g. Tinder), usually operated via smartphone, and including the special feature of users having the opportunity to display contacts in their immediate proximity.

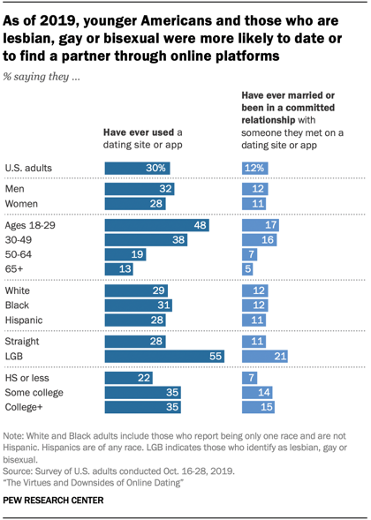

As evident in this chart from Pew Research[3] (Anderson et al., 2020), 30% of U.S. adults, and 52% of those who have never been married, report ever using a dating app or site. There is greater use by those who are younger, correlating to exposure to dating apps and culture of use among peers. The median age of those using a dating site was 38; compared to 29 among those using a dating app. And as indicated below, LGBT adults were nearly twice as likely to report ever using a dating app or site.

There are other ways of finding dating partners online, of course, including using social media to get information about someone or to ask someone for a date. Not surprisingly, social media is more popular with teens, who say they show interest by “friending” or “liking” a post or by sharing, though this is now likely to occur through more popular platforms like Instagram and TikTok.

With the growing frustration with dating in the 21st century (at least according to this report), do these apps help? They’ve seemed to enter the public perception as an option for finding dates, with reactions widely varied as to whether they have a positive or negative effect (Anderson et al., 2020). Perceptions of their safety vary as well, though those who voice more concern have never used a dating app.

Reasons for use

The major reasons that people use online dating include meeting those who share similar interests or hobbies, meeting people who share beliefs and values, finding someone for a longterm relationship or marriage, having a schedule that makes it hard to meet interesting people in other ways, or meeting people who just want to have fun without being in a serious relationship (Eichenberg, et al., 2017). COVID-19 and its imposed isolation made finding dates a particular challenge.

Online platforms can help users overcome barriers in relationship initiation. These may be physical barriers such as geographic proximity, or psychosocial barriers such as shyness. Asynchronous conversation can give individuals time to prepare a response, and can accommodate those with different schedules. Online initiation also enables a presentation of self in ways that minimize “gating features” (McKenna et al., 2002) such as physical appearance or voice quality that affect initial impressions. Although dating sites and applications include features that approximate reality through photos, videos, and videoconferencing, at each step of the relationship formation process, individuals have agency over the degree of personal information they divulge.

Online sites may be more effective for those seeking others in “thin markets,” or niche markets (Scwartz & Pelotta, 2018), or seeking those harder to find in real life. For example, if someone lives in a rural area and is looking for an LGBTQ partner, it may be easier to find that person through an online site. Online sites may also be more effective from a safety standpoint. In the above example, online sites are often safer, especially in rural communities, as in-person encounters may be met with a hate crime.

Though dating apps can be efficient and offer control, there is a heavy need for self-branding and self commodification (Hobbs et al., 2017). Indeed, Bauman (2013) argues that the security of relationships has been compromised by technological change, specifically in the way that our use of the internet and digital technologies has created a game of commodification — or the selling and packaging of the self. For some, this type of exposure can ultimately be harmful to that self. Dating apps can also introduce possible miscommunication, misrepresentations, and damage to new relationships or to an individual. [4]

Finding happiness

Are dating apps effective? Just as we might have to define the “impact” of technology on a relationship, so too might we need to define “effective” with regard to dating apps. If someone is looking to meet someone for casual dating, or for a “hook-up,” effectiveness is far different than for someone looking for a long-term, committed relationship. And while the personal dimension of effectiveness may relate to perceived success in matching, the mechanics of dating app effectiveness (e.g., algorithms for matching, software programming code) are a behind-the-scenes consideration.

Satisfaction

In debates held in the undergraduate classes that informed this book, many agreed that initial and sustained connections taking place online are very similar to those ocurring offline: two people meet each other through a conveyance that offers filtering — through friends, at a known neighborhood bar, activities, through an online service that provides information. In nearly all classes, students offered evidence of marriages resulting from the use of dating apps (including students’ mothers or fathers in second marriages), and satisfaction with the outcome depending on intention.

In Pew’s 2019 research, the majority (61–71%) of those using dating apps reported positively that the apps help in finding someone who is physically attractive, has shared interests, that they wanted to meet in person, and who shared their ideas for a relationship (Anderson, et al., 2020). Within these numbers there were differences by gender (e.g., men finding it harder to find someone who shared their interests), and education (e.g., those with less education reported less success). Two-thirds (66%) of online daters have gone on a date with someone they met on sites, and 23% of online daters have entered into marriages or long-term relationships with someone they met. Older research following couples who met online indicates that their marriages or committed status relationships were as stable and happy as others. In one study, online couples married sooner after their first meeting, compared with others (Baker, 2004), and were positive about their futures together. In another, couples who met through social media, using networked connections, did not have a higher risk of divorce or separation than those who met offline (Hall, 2014). And in a third study from a national survey in the U.S., couples who met online dated more and had a lower rate of separation than those meeting offline (Aditi, 2014).

In Hobbs et al.’s research (2017), daters said that while apps may be superficial, they’re pleased when they are selected by another person. The majority said that apps gave them a feeling of control in finding partners, and 87% said it gave them more opportunity for finding partners by expanding the size and scope of their social network. Just over half (55%) reported that it helped them find a date or, for 25%, a sexual partner. Nevertheless, participants indicated that they would prefer face-to-face searching. Qualitative investigation within this study revealed that, for some, using the dating app had a therapeutic benefit. After experiencing a personal setback, the representation of the self they wanted to be offered validation and encouragement.

Satisfaction also appears to be related to understanding how apps work (i.e., how matches are made) and an awareness of digital data sharing. In Pew’s 2019 research, just over half (58%) of those who used dating apps indicated knowing the realities of “match-making.” (Turner & Anderson, 2020). The majority (69%) of those reporting positive experiences understood the matching process. They were more likely to report that using the apps had a mostly positive impact on their dating and relationships, which may or may not include believing in the effectiveness of the algorithm. Pepper Schwartz, a sociologist and academic who worked as a consultant on a dating app’s creation (Scwartz & Pellotta, 2018), observes that “the majority of these sites offer no hard evidence to show that their algorithms can actually procure better dates, partners, marriages, sex lives, etc. than human judgment alone.” (p. 62). Perhaps positive perception leans toward efficiencies in finding people and filtering a vast (or, in some cases, expanding a limited) pool.

How dating apps work

How companies’ algorithms create matches is uncertain. Heilwell’s reporting on the topic points to the artificial intelligence (AI) that uses data provided by the user, “likes” by the user, and “likes” about the user, in addition to data from add-on services (which helps make the apps free). Tinder incorporates data about use of the platform (location, activity), and platforms like Hinge track likelihood of exchanging phone numbers and satisfaction after dates. Heilwell also notes that data from other users of the app can inform who is matched with a singular user in something called “collaborative filtering.”

Understanding how apps work may also involve seeing the gamification elements that keep them interesting. Bumble, for instance, makes matches disappear after 24 hours if they aren’t contacted. Other game-like features include continuous scrolling, delivering prospects at a certain time, and, of course, the thrill of “matching.” While making dating apps fun to use, these elements can also make them quite time-consuming. The amount of time that people spend on dating apps leads to questions of their actual time-saving nature.

Challenges

For all of their efficiencies and effectiveness (perceived and real), dating apps can create challenging experiences. Early critics were concerned that the open nature of dating online, as with social media in general, would lead to less civil behavior, and some users — particularly women and LGBTQ users — do feel harassed and unsafe There are concerns as well about data sharing and privacy. And even just using the apps can lead many (45% in Pew’s study, Anderson et al., 2020) to feel fatigued and frustrated. The “paradox of choice” can stymie the ability to choose from such a vast array of matches. Eisenberg et al. (2017) observes that finding people online sets up an unrealistic expectation of the “optimal partner,” making relationships seem superficial and non-binding.

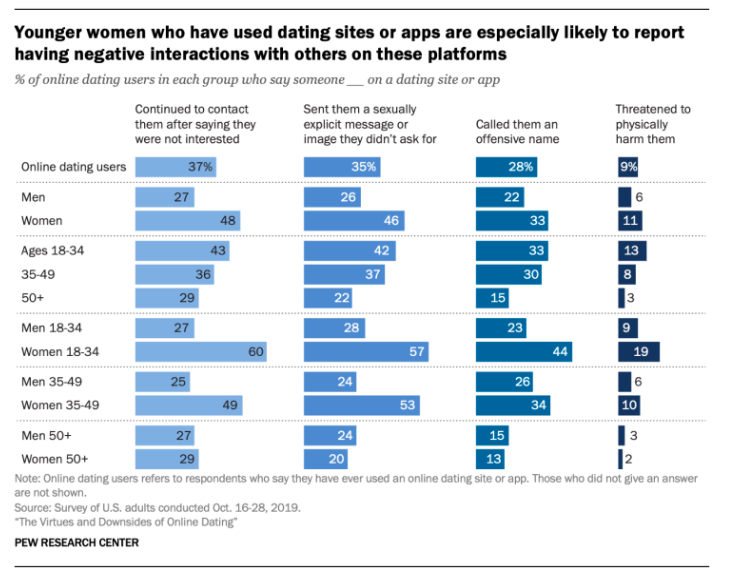

Safety and civility

Interestingly, most users of dating apps (70%) feel that it’s common for people to lie about themselves to seem more desirable (Anderson et al., 2020). Fifty-four percent of online daters say that someone else has seriously misrepresented themselves on their profile, and 28% have been contacted in a way that made them feel harassed or uncomfortable. A breakdown of those reporting negative interactions is shown below. Across the four questions asked in Pew’s research, LGBT daters were significantly more likely to report having experienced harassment. While these behaviors can also occur in offline encounters, networked, efficient internet can make the fall-out from use of dating apps a greater possibility.

Another issue of safety lies with the internet’s efficiency and speed in finding information (or people) that align with specific search interests. Eichenberg et al. (2017) write about “barebacking” (a metaphor for having unprotected sex), and those who search online to heighten the risk of infecting themselves with HIV or other sexually transmitted disease).

Data sharing and privacy

Like other interactive applications, dating apps collect user data, including age, gender identification, gender preferences, religion, political affiliation, and location (Heilwell, 2020). And users share videos, photos, and potentially their activity on social media. While visiting an app, data from other sites visited is fed to the app and used for marketing purposes and sales to third-party companies. Those concerned about privacy and data sharing report less positive experiences with dating apps. In the Pew study, 58% of users reported concern about data sharing. In nearly the same frequency as those reporting knowledge of how the apps work (approximately 67%), those concerned over privacy and data sharing reported having negative experiences and viewed the apps as having a negative impact on their relationships. Slightly greater concern was expressed by older users (30 and up).

With this overview of ICT use by couples within the family and in couples on the way to building family, we now move to children’s use of ICT across the complex trajectory of their development from birth through young adulthood. With a systems perspective of families, as you read, consider how other members of the family are affected and affect the impacts of ICT and children.

- Students may pull from resources in their courses on intimate relationships, family theory, couple and family therapy, contemporary families and couples, gender studies, and family sociology to apply to this chapter. ↵

- Readers are encouraged to explore the Gottman Institute site for information, training opportunities, and additional resources: www.gottman.com. ↵

- Readers are encouraged to visit the full report from Pew Research, which provides an array of statistics on perceptions and experiences with dating apps in the US. ↵

- Misrepresentations through dating apps have become fodder for social media, the news, and reality programming. Examples include “Catfish” and “The Tinder Swindler.” ↵